The Business of Who Owns What

In the revival of post-pandemic tourism, travellers have been packing museums, hotels, and flights. Amidst the chaos of travelling, you may spot the Sheraton or Hilton airport hotel, both of which are HotelBeds clients. HotelBeds is the world’s leading bedbank and portfolio company of Cinven, a global private equity firm that raised €10 billion in their seventh fund. If you’re scrolling through TikTok while awaiting boarding, ByteDance, the developer of the app, received KKR funding in 2018. The Becel margarine on your sandwich is produced by Upfield and the aircraft maintenance crew is contracted by Atlantic Aviation, both portfolio companies of KKR. The tourism industry is just one of many that is largely owned and operated through private financial operations—or rather, “asset managers.”

Financialization has created a disconnect between consumers and the original source of the asset, but it’s quite literally everywhere. In fact, it’s increasingly pervasive in our environment and society.

In 2023, the EU Commission updated Regulation EU 2020/852, or the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), in recognition of the material effects of investment decisions on the environment and society. The SFDR is a set of requirements for disclosing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information. This instrument targets Financial Market Participants (FMPs) or financial advisors who operate or engage in trading within the EU—given the globalised nature of the industry, this impacts major players in the Americas and Asia-Pacific, too. SFDR also targets greenwashing, or rather, the marketing practice of making environmentally unfriendly business practices appear sustainable to prospective investors and the public. Asset managers must now consider negative externalities of investment decisions on the environment and social justice.

Under the new EU instrument, asset managers are mandated to disclose environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information of their funds’ portfolios (Level 1) and firms’ policies (Level 2). However, portfolio companies that make up asset managers’ investments like Atlantic Aviation will effectively be indirectly impacted. In order for asset managers to provide sustainability risk assessments, portfolio companies will also have to disclose the impact of the investments they receive. All companies with private money backing them will consequently have to conduct internal reporting. And more importantly, SFDR was designed to impact prospective investment decisions as European asset managers want CSR badges on their funds to avoid public scrutiny.

While SFDR reinforces a norm of standardized reporting for ESG investing, the question is whether it might turn out to be an effective tool to further greenwash long-standing industry practices. Are funds still investing in the same genre of portfolio companies prior to SFDR, or have LPs changed their fundraising strategies in response to this greater scrutiny? Has this, in turn, forced more asset managers to take on better business practices to qualify for a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) tag that classifies them as “sustainable” products? At the heart of the issue is whether or not disclosure is an effective tool in enacting better business practices.

Are there Alternatives to “more and more disclosure”?

Starting a business is tough, and what immediately comes to mind for financial operations and market expansions are bank loans and, for larger endeavours, bonds and public listings on various stock markets. These were some of the first capitalisation methods adopted in western countries during the 19th century and remain important to this day. However, capitalisation methods have expanded drastically since then.

For example, there were only 312 private equity firms by the end of 1990. This number has grown to more than 5,391 firms with total assets under management at approximately $2.83 trillion from $500 billion between 2000 to 2017. US equity markets represent 46.2 percent of global equity market capitalisation, followed by China (10.6 percent), and the EU (9.1 percent).

What explains this evolution? In the US, corporate ownership has evolved from the hands of few robber barons with weakly diversified portfolios and high levels of control in the 19th and early 20th centuries, to more dispersed stock ownership by the mid- to late-20th century. Though, as Tim Smart points out, stock ownership has always been concentrated within the top decile of income earners in the country. However, proponents of the view that stocks have democratised over time, like political economist Benjamin Braun, argue this is mainly due to progressive antitrust laws, higher federal taxes during wartime, the 1920s stock market boom, the rise of the middle class, and an overall postwar boost in public and private retirement benefits, which allowed pension funds to become corporate America’s most dominant shareholders with highly diversified portfolios.

However, a new dragon entered the den in the 21st century: asset managers. While pension funds gather household retirement savings, asset managers pool the holdings of a range of investors including insurers, sovereign wealth funds, and other entities. Pension funds can be LPs themselves. They’re massive.

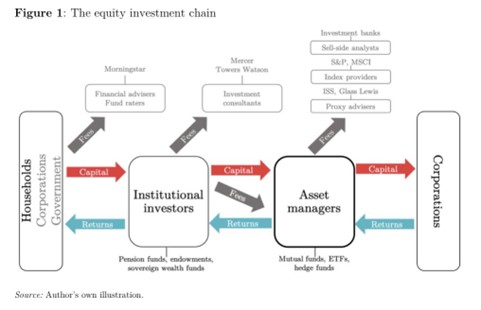

Figure 1. Investment chain under asset-management capitalism (illustration from Benjamin Braun)

While pension funds invest on behalf of employee contributors for their future benefit, for-profit intermediaries profit off fee-based business models: asset manager employees get a cut of the returns too. The bigger the cut, the better.

The shift towards expanding asset management chains is also rising in Europe. With the 2008 financial crisis, market-based funding substituted bank-based financing to a certain extent in North and Western Europe. Since then, they’ve similarly been taking strides towards growing financial-market structures. However, trends like the governmental and corporate focus in ESG-oriented performance amidst this expansion are imposing new challenges for asset managers and private equity firms: namely, managing the operative costs of compliance.

Is SFDR trailblazing a greener path for investment decisions?

The SFDR was launched as one of the key pieces of the EU’s Action Plan for Sustainable Growth following the 2016 Paris Agreement. This marks the world’s first major regulatory move to codify ESG disclosure.

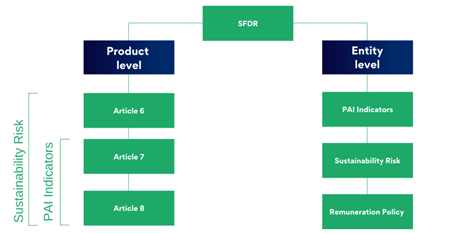

Asset managers must now disclose at two phases of their operations. Level 1 (effective since March 2021) requires general disclosure on fund portfolios such as the sector in which it’s investing. Level 2 (in effect in January 2023) is more prescriptive, mandating detailed disclosure at both the product and entity levels. Funds can be entitled to distinction awards for sustainable practice at this level. Entities refer to a firm's policies and operations, while products include various financial offerings such as investment funds, insurance-based investments, and pension plans, among others. Sustainability-related risks caused by investments at the entity level are informed by EU Taxonomy, and FMPs may also consider Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) indicators. These are a set of quantitative metrics that cover ESG criteria such as greenhouse gas emissions and board gender diversity.

Figure 2. Illustration of SFDR disclosure phases (ESG Tree)

Crucially, to complete these indicators, detailed information is required from individual assets that comprise fund portfolios. As Deloitte Luxembourg has noted, this presents a huge challenge for asset managers, both because the indicators are complex and are not all standardized metrics. Further, data collection can be unreliable. This is why recent SFDR discussions have been focused on these indicators.

More importantly, the answer to the major question of whether SFDR is effectively promoting sustainable business activity depends on how we think about disclosure and its effectiveness.

A 2016 study at Harvard University presented an analysis of eight disclosure policies, or “transparency systems,” in the US. Among the three that were effective in advancing their regulatory objectives is Los Angeles County’s 1997 restaurant grading system. Under that regime, which was created to (describe aim) restaurants had to display their government hygiene score from A (good), B, or C (bad). In applying this system, it turned out that C-graded restaurants saw revenue decreases while A-graded ones saw increases. In their research, Fung et al. described ‘double embeddedness’ as a feature of disclosure effectiveness: transparency systems where users can provide feedback to disclosers would result in changing discloser behaviour if they found value in those responses for their goals.

SFDR’s PAI indicators converts complex information into user-friendly menus that promote ‘comparison-shopping.’ SFDR is changing the landscape of information asymmetry between asset managers and investors. Given that investment firms must report on the same set of core PAI indicators, a key aspect is comparability and benchmarking of ESG performance, either across different funds or across assets within a fund.

PAI indicators show investors the sustainability objectives of the product they’re buying into for what it is—the way hungry customers can (hope to) adequately assess the restaurant’s hygiene before stepping in for their meal. While there are no official requirements to publicly share PAI performance, it is expected that investors will request this information as LPs have shown a social appetite for sustainable business practice, especially in the EU. Goldman Sachs’ 2022 report on the EU’s SFDR suggests that Article 8/9 funds have significantly outpaced non-ESG funds, and likewise, it is favourable for asset managers to attain their CSR badge. Vincent Gouverneur, partner at Deloitte Luxembourg, observed in June 2022 that investors were expecting asset managers to have ESG products. LPs have their own ESG goals to meet and will choose where to put their money accordingly. Firms with Article 8/9 badges will thus have an easier time fundraising in Europe.

However, investors prefer high returns to food poisoning. The previously cited Harvard study also found the US’ Exchange and Security Act’s corporate financial reporting system to be effective. Obviously, there are incentives for both investors and disclosers if profits are on the line. If sustainability is not an objective for the purpose of being ESG-oriented, perhaps investors may factor it into their financial risk assessments. Already in 2018, the legal academic and climate change expert Cynthia Williams argued that sustainability risks pose real material, and economic, risks for investors. Should this consideration be widespread, asset managers would certainly be inclined to embed investor preferences for sustainable products moving forward.

…Or is SFDR driving up new operation costs instead of tangible sustainable practice?

What’s perhaps most interesting is SFDR’s new Level 2 mandate to classify funds. Asset managers must classify their funds’ sustainability integration into Article 6 (no sustainability objectives), Article 8 (some sustainability objectives), or Article 9 (only sustainability objectives). This means funds are being classified based on where the investments are going: funds invested in green technologies would be categorized as Article 9. Most funds with investments in Big Oil, for instance, would fall under Article 6, although even this is subject to debate as the EU Taxonomy designated natural gas a green transitional activity. And the rest… well, that’s subject to questions.

There’s been a statistical trend in classifying funds as Article 8 to veer on the side of caution. According to Morningstar, the EU fund universe is mainly dominated by Article 8 (33.6%) and Article 6 (62.2%) funds by the third quarter of 2022. It's also unclear what a ‘sustainable investment’ entails, causing many asset managers to reclassify their Article 9 funds into Article 8.

Article 8 is a broad category and funds that have ‘positive externalities’ for the environment or society can be classified as such. Section 2(17) of the SFDR define “sustainable investment” as an investment in an economic activity that contributes to an environmental or social objective and does not significantly harm any of those objectives. While PAI indicators will help qualify and quantify what constitutes ‘sustainable’ economic activity, Morningstar critiques the ambiguity in SFDR standards for sustainable investments. There’s just too much room for interpretation. The European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA) recommends EU regulators, or European Supervisory Authorities’ (ESAs), to provide further clarification on outstanding policy gaps and provide room for industries to transition in capital reallocation towards sustainable investments.

Article 8 funds are not any more pressured or obligated to make primarily sustainable investment decisions. SFDR is a disclosure mandate, not a law that forces asset managers to act more sustainably. While investor decisions based on SFDR classifications could sway asset managers to re-strategize, they can still choose to have unsustainable investment strategies—as long as their products are classified as Article 6.

In this sense, SFDR is not mandating ESG-friendly business practices directly but relies on market forces to act as a tool through which it should become easier to assess market trends. For example, natural gas remains profitable and its ‘green’ classification by EU Taxonomy make it attractive for asset managers to deploy capital in that space. Conversely, very few are investing in Big Oil or Coal, as the long term viability of as well the potential to re-sell those assets are very low. It ultimately comes down to the trade-off between assets’ carbon impact and their social necessity, or potential to retain high profits.

A Double-Edged Sword

Ensuring compliance with SFDR poses a double-edged challenge for asset managers: it demands significant time investments, coupled with the added burden of absorbing compliance costs. While Fung et al. have found disclosure policies can work, they also warn “public information is not necessarily better” if the time and resources put into it are ignored. A part of this also depends on investor behaviour to incentivize asset managers to make a switch to more sustainable strategies.

Several observers, such as the Financial Times’ Ernest Chan, have commented on the cost implications of ESG regulations like SFDR. According to Chan, the mandate will drive up costs of operation for asset managers and portfolio companies. The amount of time that is invested into legal consultations, increasingly pervasive SFDR clarification conferences, and data collection will accumulate costs that arguably could have otherwise been put into more sustainability-oriented actions. In a 2021 article published by McKinsey, it was argued that European assets managers will need to focus on controlling costs to optimize inherent operating leverage to recover from current economic shocks. SFDR has a lot of potential—but regulators will need to effectively resolve ambiguities while keeping operating costs to a minimum.

Current Trends & Challenges

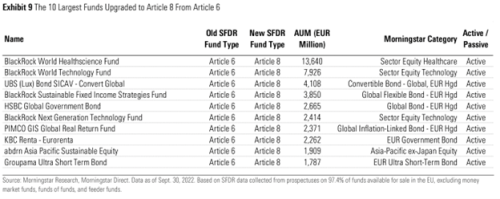

ESG enthusiasts and regulators can remain optimistic, however. So far, Morningstar reveals investors are pouring money into Article 9 funds. These funds have also seen the highest organic growth rates since SFDR was introduced. Conversely, Article 8 or 6 funds have sunk deeper into negative territory. It seems asset managers are seeing this shift and re-strategizing to switch Article 6 funds into Article 8 or 9 products. Perhaps asset managers will now think twice before developing products with no sustainability objectives. Although, SFDR regulators will have to be wary to ensure it’s not becoming the new trend for funds to majorly be classified under Article 8.

Figure 3. Reclassifications of the top 10 largest funds from Article 6 to Article 8 (Morningstar).

While publishing PAI statements is only mandatory for FMPs with 500 or more employees, nearly all (95 percent) of Article 8 and 9 funds report PAI. However, it is important to note less than half (48 percent) reported a minimum percentage of sustainable investment and only 33 percent of funds disclosed their minimum taxonomy alignment. With the first annual PAI statement is to be reported in June 2023, regulators will have to monitor its tangible effects on investor and asset manager behaviour.

Undoubtedly, regulators face a daunting challenge, but this marks a significant stride towards ESG regulations, and nations worldwide can draw inspiration from it. BNP Paribas Asset Management believes SFDR has the potential to steer the global shift towards sustainable finance. The introduction of SFDR came at opportune timing, coinciding with the expansion of Western Europe’s asset management landscape. If regulators can iron out the intricacies of SFDR effectively, it will establish a strong foundation for sustainable investments in Europe and across borders.