In a ground-breaking move, Air India has placed two ‘mega orders’ for a staggering 470 aircraft – 220 from Boeing and 250 from Airbus. With an option to order an additional 370 planes, the total number of aircraft could soar to an unprecedented 840. This deal is not only significant for Air India and the Indian aviation market but also serves as a beacon of hope for the global aviation industry struggling in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the Western economies, the multi-billion dollar order is the light at the end of a recession tunnel. President Biden predicted that the Boeing order will create “over one million American jobs in 44 states.” Other world leaders, from the French President to the British Prime Minister, have hailed this historic deal for its potential to boost the aerospace sector and drive growth.

But the deal’s most important impact is not just the metal of the aircraft themselves. Rather, the mega order sends a message to the world: that the Indian aviation story has arrived and is ready to compete on a global scale. The mega order also aligns with the highly reformist and liberalized approach to the civil aviation sector taken by the Indian Government in recent years. In the early 2000s, flying was a luxury for most and was thus limited to the upper classes. But this has completely changed in the past decade. Liberalization, a booming economy, and a rapidly expanding middle class have made India the world’s fastest-growing aviation market.

Given the multiplier effect that the aviation sector has on a nation’s economy in terms of investments, tourism, and employment, the Indian government adopted a much more aggressive and highly liberalized approach for the sector by way of the National Civil Aviation Policy, 2016. The intent behind the policy is to provide a much more liberal regulatory regime to bring more investment into the aviation sector with the overall objective of creating affordability and connectivity of air services in India. This commentary, thus, looks at the Air India mega order against the backdrop of the overall policy liberalization, regulatory reform, and capital investment plans in the Indian aviation industry.

The Indian aviation market

India’s aviation market is predicted to become the third-largest in the world as soon as 2024. This rapid trajectory is fueled by a growing population of middle-income households who increasingly view air travel as a faster (and in some cases more economical) option than road or rail. This trend is further supported by the country’s expanding infrastructure and sectoral air connectivity, the rise of low-cost carriers, and a favourable policy framework.

Passenger air traffic in India has already experienced phenomenal growth, from 79 million passengers in 2010 to 158 million in 2017. This number is expected to surge to 520 million by 2037, and Boeing’s 2022 Commercial Market Outlook for India estimates that the long term passenger growth in the country will average 7% annually through 2041. This has sparked a robust demand and investment cycle in the Indian aviation market, which is all set to add a sizable number of aircrafts to its national fleet.

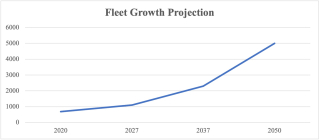

The transformation of the Indian aviation industry in recent years brought a significant 70% decline in domestic airfares from 2005 to 2018 (adjusted for inflation).[1] Domestic travel in India has grown at an impressive annual rate of 13.5%, while international traffic has maintained a steady growth rate of 8.2% over the past decade. Notwithstanding the considerable albeit short-term impacts of COVID-19, the Indian civil aviation industry is poised to make major strides in the coming years: estimates suggest that it would require at least 2500 aircraft by the end of 2038 and over 5000 by 2050.

Dissecting Air India’s privatization, turnaround and its latest historic order

Air India has truly come a long way, from its origins as Tata Airlines in 1932 to its subsequent nationalization by the Indian government in 1953. For 40 years, Air India dominated as the country’s flagship carrier, until the emergence of private airlines in the mid-1990s resulted in the company’s loss of market share. After bleeding money for years, Air India was finally privatized, with the Tata Group regaining ownership of the airline.

The Tata Group has big plans for the Indian aviation market, with a strategic vision for all four airline brands under its ownership and control. Currently, the group has 100% ownership of Air India, AirAsia India and Air India Express, and a 51% stake in Vistara, a joint venture with Singapore Airlines. While Air India and Vistara are full-service carriers, Air India Express Ltd. and AirAsia India are budget carriers. The group’s two-pronged strategy involves creating a consolidated full-service and low-cost carrier.

Consolidation plans are already underway, with Tata and Singapore Airlines announcing on November 29, 2022 the merger of Air India and Vistara. Singapore Airlines will acquire 25.1% of the merged entity, and the merger is expected to be complete by March 2024, subject to regulatory approvals.

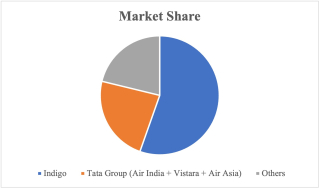

According to the Handbook on Civil Aviation Statistics (2021-22) published by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation India, the low-cost carrier Indigo continues to dominate the Indian aviation market with a 55.4% share of the domestic aviation sector in terms of passengers carried. Air India takes a distant third place at 9.7%, while Vistara and AirAsia India have 8.0% and 5.7% shares, respectively. The Tata Group aims to change this scenario and establish a strong foothold in the international passenger market.

This latest order, meant to give a new lease of life to Air India’s ageing fleet, signals the Tata Group’s aggressive strategy not only to dominate the Indian domestic market but also compete with the European and Gulf giants internationally.

The order book of these 470 planes includes, 70 wide-body or twin aisle planes for long haul flights – 40 Airbus A350s, 20 Boeing 787s, and 10 Boeing 777-9s widebody aircraft. The remaining 400 planes are narrow body or single-aisle planes, with 190 Boeing 737 MAX and 210 Airbus A320/321 Neos. With this order, Air India can quickly gain market share in both the domestic and international segments. It will allow Air India to effectively enter and compete in the long haul flight segment, becoming a formidable global network player. If the deal’s full potential of 840 planes is realized, along with the existing fleet of 113 panes, Air India’s fleet size could become the world’s largest, surpassing even American Airlines (881) and United Airlines (834) – and far surpassing Gulf giants Emirates (268) and Qatar Airways (238).

Airports, Investment and MRO

The government has set a target of increasing the number of airports in India from 140 to 220 by 2025, with 21 of these 80 new additions planned to be greenfield airports. Indeed, India nearly doubled its airports since 2014 to reach 140 in the first place. The Airports Authority of India along with other developers has planned a capital outlay of INR 98,000 crore (approximately USD 13 billion) to develop new and existing airports over the next 5 years. The growing number of air passengers is creating a huge mess at the existing airports in India. Case in point: Delhi Airport. While, the government plans for expansion of existing airports and the construction of new ones, planning has gone awry - especially since the pandemic. Land acquisition issues, environmental concerns, protest by locals and other such issues have also led to delays in the completion of greenfield and brownfield projects.

In addition to investment plans, in 2020 the government further liberalized Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) rules for the civil aviation sector, with 100% FDI now allowed in airports for both existing and greenfield projects.[2] For scheduled Air Transport Services and Domestic Scheduled Passenger Airlines, 49% FDI has been allowed under the automatic route, with FDI beyond that permissible granted government clearance, and 100% FDI allowed from non-resident Indians. In 2016, the government also launched an ambitious Regional Connectivity Scheme, called UDAN (an acronym for ‘Ude Desh ka Aam Nagrik’) to enhance regional air connectivity from unserved and underserved airports, increasing the affordability of air travel for the masses in India. The Ministry of Civil Aviation also released a passenger charter in 2019 on the rights of air passengers in India.

Moreover, the government aims to make India a ‘global MRO hub’ and has implemented several policy reforms and incentives to this end, such as:

- lowering of the Goods and Services Tax from 18% to 5% with full Input Tax Credit from April 2020;

- exempting MRO service companies from airport royalty and extra costs for five years (as part of the 2016 National Civil Aviation Policy); and

- waving custom duty on tools, toolkits and spares imported by MRO companies.[3]

This liberalized approach is part of the ongoing change in the Indian government’s stance towards being a pro-active facilitator of overall economic growth and development of the country. Air India’s privatization was also a result of this new policy approach: the government’s stance against any state-run businesses in non-strategic sectors drove the critical change, along with the carrier’s massive debt and need to raise resources through disinvestment. India’s current Prime Minister clearly stated this call for privatization across-the-board (save for a few core strategic sectors), declaring that “government has no business to be in business.”

Looking ahead

The Air India deal clearly indicates the growing significance of the Indian aviation industry on the global stage. However, despite government policy measures and investment, much remains to be done in the coming decade to unlock the industry’s full potential in India. For instance, while Indian airports have grown considerably in recent years, the development of large network hubs, of the calibre of those in Dubai or Singapore, is essential for Indian carriers to truly become global players.

Another challenge facing the aviation industry is the shortage of skilled and experienced human resources. Air India, for instance, currently employs nearly 1600 pilots for its 113 odd aircraft but will need an additional 6500 pilots for the 470 aircraft it has just ordered. While India might be a labour surplus country, the availability of skilled labour remains a problem that the government has been trying to address for several years. India produces 700-1000 commercial licence pilots in a year. This is much below the annual demand for pilots and while the government has taken initiatives, the lack of infrastructure at flight training organisations in India is major issue. The government has tried to address the shortage by issuing Foreign Aircrew Temporary Authorization (FATA) to bring in foreign pilots. However the number of FATA holders is just 82, compared to over 9,000 pilots employed with airlines in India.

Yet domestic and international demand is fast-increasing. More Indian carriers, such as Indigo (which already placed an order for 300 aircraft in 2019) and new entrants like Akasa Air, are expected to order additional aircraft for fleet replacement, growth and expansion in the coming years. As such, the Air India deal is likely just the beginning of large Indian aircraft deals – but more than just aircraft will be needed for India’s carriers to meet the demand.

Mr. Eshaan Bansal, LL.M 22' Graduate, McGill Institute of Air and Space Law

This commentary represents the personal views of the author.