The variation of five housing prototypes was an outcome of a specific social, historical and urban context, however, they were just different fruits that stemmed from the same planning principles. By comparison, the Old & New Shi-ku-men lilongs were the most ground-related, traditional courtyard pattern of dwelling. The New-type lilongs released houses from the traditional enclosing pattern, and integrated open characters into the new compact urban dwelling. The Garden lilongs, in semi-detached or detached form, were land-consuming and were special types made for special group. The Apartment lilongs recognized the high land value, and conformed to the modern multi-storied housing construction.

3.1 The old Shi-ku-men Lilong house

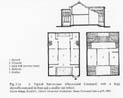

The earlier style of the Shi-ku-men houses had adopted the general pattern of row-housing which originated in London, yet the layout and structure of each house unit derived spatial concept from traditional Chinese dwelling models of San-he-yuan(7) or Si-he-yuan(8) prevailed in the south-east China region. Hence as a variation, the basic housing prototype of Shi-ku-men lilong took the form of a main two-storied building body at the front enclosing a central courtyard and linked to a rear one-storied building body through a light-well (Fig.3.1a).

Layout (Fig. 3.1b)

On the ground floor, the house comprised: one spacious main room, known as Jian(9), on the central axis facing towards a front courtyard; two secondary rooms, known as Shang(10), placed symmetrically beside the main room. The central room was used as a drawing-room or ancestral room with detachable floor-to-ceiling French windows, while the secondary rooms were used as bedrooms or library. A stair-case, generally with one landing, was located at the back of the central room, and lead to the second-floor where more bedrooms were located. A lower building body, consisting of service rooms like a kitchen and storage-rooms, was located at the back of the two-storied main body and linked to the front by a narrow service courtyard. The service courtyard, 1.2m ~ 1.5m in width also functioned as a light-well. The house was accessible from side lanes respectively from the front and from the back. The front lane gave formal entry to the house; the rear lane, often called the service lane, was used for preparation of cooking and as playground for children (Sheng, 1987, p.332-340).

In some cases, there were three Jian-rooms instead of one Jian in the central space. The greater the number of jian, the more prestigious and wealthier the family was (Fig. 3.1c, Wang, 1989, p.47).

The courtyard was enclosed by a 5m-high brick wall at the front, having a stone-framed opening. In the Old Shi-ku-men Lilongs, slabstone was used as the door-frame, while traditional Chinese wood planks was used as door-leaves. This seems to provide some clue to the name used for this type of lilongs, since "shi" means stone and "men" means door, and "Shi-ku-men lilong" may imply that the buildings were featured with stone-framed doors. In reality, the most prominent impression one can conceive about this enclosing type of dwelling when viewing from outside, was its strong rhythm of stone-framed doors echoed in the side lanes (Fig. 3.1f, refer to exterior elevation).

The lanes of the settlement were only 3m wide, but still ensured the interaction of outdoor activities, both familial and neighborly (Sheng, 1987, p.34).

Fenestration

The house was conceived to receive most of its light from the internal front and back court-yards controlled by the family rather than from exterior public space. The courtyard was conceived as a traditional way to individualize the house, and more importantly, to solve the problem of ventilation and sunlighting in the ground-floor space in long narrow lots. With the existence of courtyards, sunlight falling onto the internal surrounding walls can be moderated. The hotter temperature of outside open space and lower temperature of inside open space generated an air pressure gap which promoted a wind draught that can be trapped into the courtyards to ventilate every room (Zhang Jianmin, 1992, p. 104). Cross-ventilation through the house and a nice micro-climatic environment surrounding the house was thus attained (Fig. 3.1d).

Large screen of French windows in central room improved the sense of spatial transparency and visual fluidity in the interior space. The French windows can all be removed when there was a need for large space to accommodate the traditional ceremonies or family gatherings. In this way the drawing-room was united with the courtyard, allowing openness and commodity within the defined space (Fig. 3.1e).

The rear part of Jian- and Shang-rooms relied on the light-well for ventilation and lighting. Auxiliary rooms like kitchens received light from service lanes and light-well. The second-floor space has plenty of resources and means for lighting and ventilation.

Exterior

Seen from the outside, the house, enclosed by high wall, with few fenestrations, maintains its inward-looking character and sense of integrity (Fig. 3.1f). The appearance was delicate and rich in details. The repetition of stone-framed doors on gray-bricked exterior walls added up a strong sense of rhythm to this enclosed pattern of living. Traditional architectonic elements were kept in the elevation.

Structure

The house plan was facilitated by the flexibility of structure, which was based on two bearing walls on the east and west ends of the unit lot, and wooden posts defining interior bays and partitions. The bays were generally 3.6m - 4.2m wide (Wang, 1989, p.45). The lot size was a multiple width of the structural bay (usually three or five times of the bay) and usually 16m deep. The traditional wooden-truss system was adopted for the building's roof structure. The wall structure was a mix of brick-and-wood, with the wooden posts as bearing structure and the brick wall as an infill and partition (Fig. 3.1g).

Interior Facilities

The interior facilities were poor. Bathrooms were not conceived as an integral feature in the house. Every family used a night-stool (also known as a chamber pot), usually placed in the light-well, functioning as a toilet. These night-stools were emptied every morning by farmers who came to door to collect them. Electricity, heating and gas were not applied to the house yet (Xu Jingyou, 1983, p.21).

Summary

The climate in Shanghai is warm and humid for a good part of the year, part of daily life takes place outdoors. Apart from their functions as supplementing space for ventilation and sunlighting, the lanes and courtyards provide a hierarchy of transitional space from the most public to the most private. While the lanes promote communal and neighborly outdoors interaction, the courtyards assure privacy and personalization in familiar daily living (Zhang Jianmin, 1992, p.105).

3.2 The new Shi-ku-men Lilong house

After the collapse of Chinese Empire in 1911, the traditional extended families started to disintegrate. Migrants from the countryside were attracted to Shanghai by the promise of jobs in its growing industry. Population grew sharply. Lilongs had to be adapted to suit the low income of families who would afford and required less space. Land speculation increased rapidly. Concern of land-use efficiency took hold. Under this circumstances, the Old Shi-ku-men Lilongs were modified into high-density scheme with reduced or minimum courtyards.

Layout (Fig. 3.2a)

The most obvious modification in plan was the abandoning of traditional layout which were one Jian and two Shangs enclosing a center courtyard. Instead, houses were mostly comprised a single Jian, facing on to a reduced size front courtyard (Fig. 3.2a-a). Only the end units of a housing row were exceptionally composed by two rooms as one Jian and one Shang, enclosing a courtyard at the front (Fig. 3.2a-b, Sheng, 1987, p.35-36). The composition of two building bodies for a house - living zone at the front and service zone at the back, still remained.

Besides the reduced number of rooms, another major modification was the reduced size and height of rooms. Some lilongs put up three-stories in the front building body, and the service space added up to two stories. The living and service zones were linked by 1.2m ~ 1.5m wide internal corridor, which supplemented light to the kitchen and rear part of living space. The house were still accessible from the front and the back (Fig. 3.2c). The size of the front courtyards shrank to 2m by 3m.(Wang, 1989, p.47-50).

Function of each room more or less remained as the same as before. However, with the change from a horizontal pattern of layout to a more vertical one, separation of different functional zones took place. The ground floor was used for public family activities, and the second and third floors were used for family private activities. The staircase kept its location at the back of the central hall, but it had two landing due the reduced width of the Jian-room.

Fenestration

With the gradual shrinking of inward-looking atmosphere and diminished size of internal courtyard, windows on exterior walls increased to facilitate lighting and cross-ventilation throughout the house. The central hall had a full screen of detachable French windows giving to the courtyard.

Exterior

The idea of stone as the door-frame of the front entrance remained, so did the word of Shi-ku-men in the lilong' name. However the houses were enclosed by lowered brick wall (Wang, 1989, p.50). The difference of building height between the front and back two bodies, more fenestration on exterior walls, conveyed a vivid look to this type of lilongs (Fig. 3.2c). Traditional ornamentation persisted.

Structure

The structure retained the mixed brick-and-concrete structure for walls and wooden truss for roofs. As the lot size shrank, the width of a bay reduced slightly from 3.6m - 4.2m to 3.2m -3.9m. The width of a lot was one bay's width for a central house unit, and two bay's width for a corner house unit. The length of a lot was also reduced to about 14m.(Wang, 1989, p.50-52).

Interior Facilities

Interior facilities did not changed.

Summary

The New Shi-ku-men lilongs had both advantages and disadvantages. The highly densified minimum-court scheme had recognized the high land value, and optimized the housing number in a given site, hence it was more appropriate for the dense to the compact urban context. By reducing the number of interior bays, or by diminishing their size, a maximum number of residences could be erected on a given site(Ged, 1994, p.174). The houses, usually occupying only one-forth to one-third of the lot size of that Old Shi-ku-men houses, achieved highest density (11) as 70% ~ 80% (Yu Minfei, 1992, p.148). The separate layers for private and public spaces, economic use of courtyard, and spatially compact layout, etc., reflected a new mode of life for small-size, low-income families.

The Shi-ku-men type of lilongs, no matter old or new, still favored a traditional way of living. Highly introspective, houses fostered an intense sense of privacy and tranquillity, which kept out the hustle and bustle of the city and the sight of the public. Within the enclosing wall, the houses also allowed an elastic way of utilization and personalization of one's private domain (Xu Jinyou, 1983, p.24). However, poor sanitary facilities and interior utilities, were some of the severe problems existing in Shi-ku-men lilongs.

3.3 The new-type Lilong house

With the development of local economy, the housing had undergone profound changes. Polarization of the rich and the poor promoted the generation of lilongs in more styles to suit the needs and to favor the taste of different social class. Except the highly densified, minimum court schemes, there had developed an urgent housing need for a new emerging social class. The New-type Lilongs came into being in response to this need. Its three different modes of house models provide more choice and enriched the housing market (Wang, 1989, p.55).

The great flexibility and adaptability provided by variation of house models, the significant achievement in interior function and facilities, and consideration in livability and comfort, made the New-type the most favorable and successful type of lilong dwelling. Developed in large scale, they are the most important among all existing lilongs today. Most of them are to be upgraded under the municipal rehabilitation program, and will be kept in use for the next several decades after improvement(Yu Minfei, 1992, p.151).

Layout

The layout of a house could be composed basically in the one jian, one-and-half jian, or two-jian modes. The buildings were generally three-storied high. Rooms were more defined with their usage. Waste of space decreased. The three different modes of layouts in the New-Type Lilongs, with their wide variety of modification and combinations, provided a diverse range of house models different in sizes, layouts and standards.

I. The One-jian Layout: (Fig. 3.3a)

The standard lot size of a one Jian house model was 4.2m by 12m. The layout was basically composed in this way: the Jian used as a living room containing dinning area facing to a front courtyard, a kitchen and a bathroom as the service area located at the back and linked to the front living zone by an internal corridor. The front courtyard, 2 - 5m in depth, were sometimes enclosed with brick walls, and sometimes fenced with steel-trellised frame or hollowed brick wall, in such cases the courtyard turned out to be a front garden. Small in size, the courtyard was considered more manageable. The house could be entered either from the front or from the back. The internal corridor also functioned as a light-well, 1.0 -2m wide, supplementing lighting for the bathroom and dinning area.(Sheng, 1987, p.38-40).

On the second story, there were a master bedroom, bathrooms and a library. The third story was used as bedrooms for children and guest-rooms. As the idea of introspecting and inward-looking atmosphere gradually dying out, off-ground open space such as balconies, roof terraces were added on upper floors to increase the sense of openness.

Compared to the other two models, the one-jian unit is lack of necessary space for circulation, which led to direct entry into living-room and resulted in disturbance between different activities. However, the direct entry into the kitchen allowed a more frequent use of service lanes, and promoted more social contact, since homemakers could do cooking preparation in service lanes while watching children playing. The side-lanes become an extension of service zone, very important in daily familial and neighborly activities (Zhang Jianmin, 1992, p.105).

This model had some disadvantages. The compact lot size lead to the most coverage of building mass except small void space for courtyards. The limited surface of exterior walls restricted ventilation and lighting, since they had to rely mostly on the one-spanned front and back exterior walls, as well as the internal light-well. The privacy of the house was not very good. The partition walls between every two units were not well insulated. Acoustic disturbance couldn't be prevented(Zhang, 1992, p.106).

II. The One-and-half Jian Layout: (Fig. 3.3b)

Based on the one jian house model, a half jian was added to the house aiming at solving the problems of insufficient circulation and private open space. At the front, the half jian was converted to a circulation corridor which consisted of entrance and stair-case; at the back, it was used as a service courtyard located beside the kitchen.(Sheng, 1987, p.47-49)

The existence of corridor and side yard improved physical function of the house considerably. The front corridor eliminated traffic disturbance to living space and helped organize the horizontal and vertical circulation of the house more clearly. The side yard enhanced the efficiency of service activities as food preparation, cleaning and laundry areas. Both spaces also functioned as spatial insulation inserted between two dwelling units, neighborly interference was thus reduced and better privacy attained (Wang, 1989, p.64). The diagonal location of the two, allowed more direction of ventilation throughout the house and more exterior walls for fenestration, for example, the side-yard enabled the kitchen to have west-facing windows.

In one and half-jian unit, the second story was used as sleeping & reading area for the master, and the third story was used as sleeping and playing area for children. A roof terrace was created on the third floor above the kitchen, offering spacious above ground semi-open space - terrace.

The simple but creative integration of half-jian into layout helped improve livability of a house within its compact urban lot. The house, occupying an average lot as 6.3m by 12m (Wang, 1989, p. 55-60), had double access and double yards, usable open space, separation of private & public zones, clearer spatial order, and better ventilation & lighting condition.

The use of side yard as extension of family's living space, created a spatial fluidity running from one family's side yard to the service lane, and into another family's side yard. This also allowed a flexible way in conducting housework and neighborly social interaction (Xu Jinyou, 1983, p.23). Residents, living so close to each other, sharing their daily life, established a strong sense of friendship.

III. The Two-jian Layout: (Fig. 3.3c)

The two-jian house model basically comprised: two spacious rooms, - a drawing-room and a living-room - one recessing from the other; the service areas located at the back linking to the front building body by an internal corridor. The second and third story were not much changed from the previous models, except the number of bathrooms and standard of interior facilities were raised. The usage of rooms was more defined (Sheng, p.40, 1987).

A garage was integrated into the service zone as two-jian house model was created to cater to higher income families. Sometimes garages were put together at irregular-shaped area of the settlement site, wherever considered not good for housing. The width of side lanes were generally increased to 5 ~ 6m, assuring enough space for vehicles to pass (Sheng, 1987, p.40).

The normal lot size ranged from 7.2m by 9m to 8m by 12m. The building mass, having increased width and decreased depth, would naturally ensure better lighting and ventilation throughout the house(Wang, p.66, 1989).

The 3 - 5m deep front garden became a nice amenity of the house. It was ample and manageable in size, and protected with steel-framed fence or 1m high brick wall. It allowed much personalization, and enhanced the sense of ground-relatedness and openness of the house. Children could play in the garden under supervision of their parents sitting indoors. The interior space, having large windows facing onto the garden, could borrow views from the garden, without sacrificing much of its privacy. This visual and spatial permeation of interior and exterior expressed the new open way of living. Mezzanines and roof-top gardens, large bay-widows swarmed.

Circulation was concentrated and distributed on the service zone. The different location of stair-case in the service zone gave the house different advantages. 1). When the stair-case was located at the center of the service zone, rooms like the kitchen, storage, and bathroom could get direct access to it. This articulation shortened the routes of circulation (see Fig. 3.3c). 2). When the stair-case was placed at one end of the service zone, the circulation space became independent from other rooms. This placement was especially beneficial when a family divided from one unit into three different apartments, each occupying one floor. In this case, every family could enter from the back entrance, using the stair-case to access one's apartment without disturbing the other two families (Fig. 3.3d). This arrangement provided more flexibility in using the house differently during the life cycle of a family.

Overall, compared to the previous two models in New-type lilongs, the most prominent features of this model, is its better functional layout, effective spatial organization, and high quality of interior finishes and facilities (Wang, 1989, p.64-66). However, this model was more land-consuming. The spacious two jian house model was suited to large-size and high income families.

Exterior

With the abandon of the exterior enclosure walls, features and elements of an open character increased. Exterior fenestration were increased to improve ventilation. Gardens, balconies and roof terraces appeared frequently. In some cases, the front gardens were fairly big, and these houses got another name: Row-Garden lilong houses (Sheng, 1987, p.42). Traditional details like brick carvings and meticulous decoration were replaced by simple western ornamentation. Differentiation of building bodies and creative spatial organization contributed to more vivid appearance of the New-type lilong housing. By this stage, traditional inward-looking character gradually disappeared. Lilong housing step by step attained the open character of Western town house.

Structure

Concrete-framed structure, brick-wall as partitions and wood-truss roof system were the common building components in New-type lilong houses. The lots of houses also underwent evolution. Freed from wooden bay, the width of rooms slightly increased. They were generally 3.6m - 4.8m (compared to previous 3.6m ~ 4.2m), with some even to 6m. On the other hand, the depth of lots were 10m -14m, decreased from 12m -16m due to a consideration for better physical function of the house, e.g., lighting and ventilation (Wang, 1989, p.66) (12).

Interior Facilities

Large-scaled construction of New-type lilongs brought about profound changes to housing market. With the development of economy and technology, modern appliances and high quality of housing facilities, were considered an important mean to improve the physical function of houses and to produce comfortable dwelling. The adoption of bathrooms and gas-stoves in kitchens were two principle characteristics which distinguish the New-type lilong houses from the previous models. High level of interior furnishings & finishes also demonstrated profound housing revolution which was taking place during this stage.

1). Bathrooms:

For the first time in lilong's history, bathrooms as standard sanitary facilities were integrated into houses. Normally a house in New-type lilong was equipped with two bathrooms, one on the ground floor serving the servants and visitors, the other one on the second floor serving the family. For high income families, bathrooms on each floor seemed not to be a luxurious facility. For low income families, there was at least one bathroom placed on the ground floor. The bathroom on the ground floor was usually furnished with a lavatory and a toilet. The bathrooms on the upper floors were furnished with lavatory, toilet and bath-tub (Wang, 1989, p.67-68).

2). Kitchens:

Kitchens discarded the traditional briquette stoves and adopted gas ones (Wang, 1989, p.68).

3). Telephones and Garages, etc.:

Heating systems were incorporated in most of the New-type homes. Domestic telephones prevailed. For higher income families , fireplaces appeared in the living room. Garages were necessary facility and were incorporated into the service area.

4). Lighting and Ventilation Techniques:

After high exterior walls were removed, the lighting and ventilation condition of houses improved. The appropriate building distance ratio(13) (average as 1 : 0.7), assured sufficient sun-shine in the ground-floor rooms (Xu Jinyou, 1983, p.23). New devices like air-shafts were introduced in courtyards or light-wells to improve ventilation of the ground floor rooms which were adversely effected by an additional story which was added to those buildings.

Summary

Though the transformation in housing were comprehensive, the basic urban structure of a house in relation to the ensemble of the settlement wasn't affected. The maximum land coverage for housing, the most efficient way to optimize open space, had ensured a high density of 50% ~ 60%(14) for New-type lilongs (Yu Minfei, 1992, p.147).

3.4 The garden Lilong house

From 1930, with the spread of western culture and values in Shanghai, with the development of economy and accumulation of wealth in hands of the rich community, the Garden lilongs came to its prime. Its sophisticated layout, vivid elevation, various international styles, and high quality of finish and furnishings, catered to the tastes and fancy life-styles of a few well-to-do.

Layout (Fig. 3.4a)

The volume of a house model was controlled by the number of stories in height and the number of Jians in layout. The average house volume was limited to two Jians in layout and three stories in height, because this spatial dimension could maintain an efficient circulation within the house, and avoid excessive use of space.

The basic layout resembled that of the New-type lilong. However, the superiority were demonstrated by the grandness of space, comprehexity of different service rooms, and higher standard interior facilities. The function of each room was well designed. For example, between the dinning room and the kitchen, there was a meal-preparation area as transitional space used for high-standard food service; and the dinning-room also accommodated a lounge for guests to have casual chat.

The access towards the house embedded more meaning and thus additional entrances were required. The front entrance was used as formal access or for guest entry; a side entrance was added to garage and used as owner's casual entry; the back entrance remained for servants' entry. The front entrance was often emphasized in the form of a verandah, or a porch, displaying rich decoration, and was incorporated with the beautifully land-scaped grand garden, to show off the wealth and privilege of the owners. The use of side entrance by owners avoided disturbance into living-room.(Sheng, 1987, p.43)

Benefited by spacious-sized lots, flexibility in site planning was achieved. Rooms were freed from restricted site-orientation often seen in a narrow-long type of lots. Windows could be put up on any side of exterior walls. With three or four orientation and more sides of exterior walls available for fenestration, ventilation and lighting condition of Garden house were greatly improved.

A good view into the garden could be intentionally designed, and exterior landscape or scenery could be guided into interior space. Visual privacy and acoustic insulation could be attained by taking advantages of the side walls of neighboring houses. For example, by staggering around, or recessing one unit from another in the general plan, a group of houses could achieve lively and organic relationship in their general environment, but maintain individuality and tranquillity in each private garden. (See Fig. 3.4b.)

The existence of abundant private open space eliminated neighborly contact. The side lanes, which used to be semi-public space for social interaction, were utilized only for circulation. In fact, for lifestyles of well-to-do, a lot of social activities could be taken indoors - parties at home or entertainment in clubs. Telephones and cars were available for them when service and socialization were needed. Rich people living in the Garden lilongs didn't have the strong ties with their neighbors.

Exterior & Structure

The Garden Lilongs gathered a variety of European style house forms, from French, Spanish to English ranch. The exterior used many Western elements, front porches, bay windows, colonnades, to name a few. Their structure were concrete-frame(Wang, 1989, p.68).

Interior Facilities

The house interior were highly furnished and finished - full bathroom facilities, heating system, fireplaces, marble or wooden plank floors, high ceiling, and grand staircases, etc. (Wang, 1989, p.70).

Summary:

In terms of architectural form, quality of structure, physical function and interior furnishing, the Garden lilongs houses were much larger and more comfortable than other types of lilong houses. But, they required large lots and their density was very low.

3.5 The apartment Lilong house

Layout

According to their basic layout and spatial volume, the Apartment lilong houses were classified into three categories: I). the row-patterned building model; II). the dot-patterned building model; III). and the butterfly-patterned building model. They ranged from four to six storied, and were similar to modern apartment buildings (Sheng, 1987, p.45-46).

I). The Row-patterned building model used a rectangular shape of layout. There were two to six units per floor, and two to three units per landing. Basically, each unit had living-rooms and bedrooms at the front (normally south), and service rooms at the back. Since service lanes were no longer available in use for each family, a secondary staircase, serving as service access or emergency exit, was added at the back of the building for every two units. (See Fig. 3.5a.)

II). The Dot-patterned building model had a more tight and compact layout and so slimmer volume. There were two units on each floor, sharing one front entrance and one back exit. Since each unit was free on three sides of exterior walls, orientation and ventilation were generally good. (See Fig. 3.5b.)

III). The Butterfly-patterned building model was a larger-scale dot-patterned building model. Instead of two units, there were four units on each floor, sharing one common staircase, usually located on the north. Modeled after the European point-block, each unit occupied one corner of the layout. All service rooms of four units were clustered in the center of the floor plan, where ventilation and lighting conditions were poor. The service rooms maintained lighting and ventilation by having openings towards common corridors. Secondary staircases were integrated into the service area, one for every two units. (See Fig. 3.5c.)

Structure & Exterior

Adopting concrete-framed structure, the structure of Apartment buildings were good. Being 4 - 5 storied, they had most characteristics of modern apartment buildings. The exterior were stone, brick, or stucco finish, with some ornamentation including modern and Westernized decoration (Wang, 1989, p.70-71).

Interior Facilities

The interior facilities were of high standard. Full bathroom facilities, heating system, gas and electricity supply, and even fireplaces were included in the apartments. Elevator in the common lobby of a building was considered a must.

Summary

In short, Apartment lilongs was a very compact and concentrated type of lilongs, embedded many features of modern apartment buildings. However, the ground-relatedness, socially cohesive atmosphere common in traditional lilong dwelling was sacrificed or lost.

3.6. Evolution of house forms

The coexistence of different house modes in the same pattern of lilong dwelling was an inevitable outcome of social and economic transformation. The complexity of social and economic gap between users' group required housing market to produce a wide range of option to satisfy various needs and to adapt to different contexts. As lilong houses went through all these changes, the method of construction, standard of facilities, and quality of finish also improved due to the improvement of modern technology.

Reviewing the change of house models, one can observe an evolution accompanying this settlement form. Except Garden Lilongs designed for a specific income group, lilong houses were transformed to become spatially more vertical than horizontal. During the whole evolution process, the number of stories of the house model increased, while the lot size decreased. Corresponding to this trend, was the transformation from ground-related pattern to concentrated pattern of building mass. Besides the spatial and volume evolution, architectural characteristics also changed. Traditional inward-looking character gradually dying out, Western open elements prevailed.

The evolution, however, did not profoundly affect the general pattern of a lilong parti, where organization of internal lanes, common entry (gateway) from the urban streets, and hierarchical distribution of open space from the most public to semi-public, then to semi-private and finally to the most private areas, still remained in the overall composition of the settlement form of lilong housing. The idea of street shops on the perimeter of the development sites, and small-scaled home business randomly placed around internal area of the neighborhood, persisted.

To summarize, traditional hierarchical principles sustained on the general urban structure of this settlement form where this pattern of dwelling was deeply rooted, while western ideas seemed to have more impact on individual house forms. For lilongs, its exterior outfit might have changed, but its inherited spirit didn't.

7. 7 Which means a three-sided courtyard - a compound with houses built on three sides around a central courtyard.

8. 8 Which means a four-sided courtyard - a compound with houses built on four sides around a central courtyard.

9. 9 Jian: traditional name for a complete main room. It is usually the space that spans between two or several of structural bays.

10. 10 Shang: traditional name for a complete secondary room.

11. 11 Site coverage percentage.

12. 12 Some houses built after the Sino-Japan War were only 8m to 12m deep.

13. 13 Building distance ratio = Building height / Distance between buildings.

14. 14 Site coverage percentage = Building ground area / Site area.