Note Throughout this reflection, I use the umbrella term “Indigenous Peoples” to refer to Native people and communities living in North America. This reflection addresses the erasure of Indigenous individuality and traditions by European toy manufacturers. While this reflection does not refer specifically to one Indigenous group, North America is home to many people with rich and diverse traditions, histories and languages. In the United States, 567 entities are recognized1 while Canada has recognized 634 First Nations governments or bands.2

As Black Lives Matter movements re-emerge across the continent there comes a need to address forms of racism deeply ingrained in our cultural psyche. Although the role of children in the construction of political narratives is often overlooked, Eurocentrism has pervaded all levels of our Western society and continues to be conveyed through white, middle-class children’s toys. Many scholars have assessed the representation of housing and cities per children’s toys, revealing shifting narratives in the nineteenth and twentieth century.3 Countless studies have addressed how toys shape the minds and psychology of children. The discourse often focuses, through a prism of gender, on how children learn social roles through exposure to repeated stereotypical images.4 The systematic oppression of certain populations disseminated through toys to children, has gone largely unaddressed. Toys often place figures in space and within architectures, rendering them powerful vehicles of architectural colonialism. While these toys are plainly brilliant from design perspective, this essay demonstrates that some toys perpetuate racism through misrepresentation. Particularly, Playmobil® and LEGO® toys single out Indigenous people and their architecture, portraying it as placeless and rootless. Ultimately this necessitates a more diverse and comprehensive representation of the architectural canon in objects as seemingly innocuous as children’s toys. Playmobil® and LEGO® evolved from the 20th century’s interest in construction toys, providing children with a miniature and colourful replica of society. Playmobil® is a German toy brand founded in 1974. Targeting primarily children aged four to twelve, the “Native Indians” were among the first toy sets released alongside knights and construction workers. The series culminated in 1995 with the release of set no.9998, a complete “Western” Collection. The set critically conveys that Indigenous people do not exist as a self-sufficient set but are designed to be completed by cowboys and white policemen. Rarely is Playmobil® analyzed without comparison to its counterpart LEGO®. Originating in Denmark, LEGO® began with the production of wooden toys in 1932 and transitioned to plastic figurines and building blocks following World War Two, gaining popularity mostly in Europe and North America. Introduced in the late summer of 1996, LEGO®’s “Western” series proposed twelve comparable sets to the Playmobil® “Western” Collection, which were all discontinued after a re-edition in 2002.

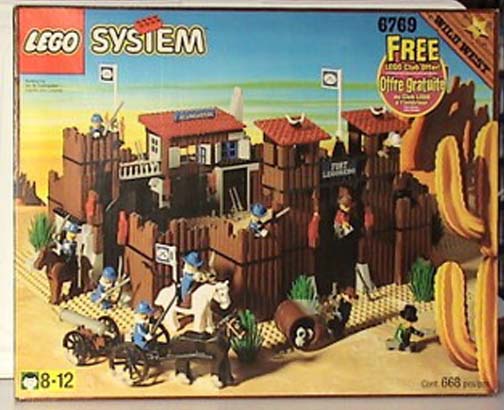

The Playmobil® and LEGO® sets are practically mirror images of each other. Both sets include a canyon with “Indian” mini-figures, a canoe, decorated horses and bow and arrows. LEGO®’s mountain includes a boulder positioned to roll onto and destroy the site composed of a tipi, fire, and totem pole. The Playmobil® set includes a wagon, recalling settler’s mode of transportation to “conquer” the West. Both forts are composed of rearrangeable sections protected by a main gate and watchtowers overlooking a central courtyard and jail cell. Revolvers, rifles, and a gun on limber complete the set, clearly outnumbering the Indigenous both in artillery and manpower. Cavalry, colonels, soldiers, and bandits occupy the space exuding a sense of control. While the Playmobil® or LEGO® games lack set objective, they allow children to develop an understanding of space and belonging. The architectural elements do not emulate a real destination, but the implications are not trivial. The landmarks and structures opposing the tipi remind the child of the triumph of the white sheriff and cowboy, forging a sense of space in which the “Indian” never seems to belong. These toys are more than harmless plastic blocks; they are equipped with the ability to stage complex dynamics of identity, race and belonging.

Toys to Narrate and Educate

The current concept of toys as a child’s plaything emerged in the 19th century, when for the first time, children formed an autonomous category that required its own tools to support its cultural development. There is a strong lineage of construction toys marking the 20th century that architects, such as Bruno Taut or Charles and Ray Eames, have used to express forms and ideas. Such toy sets inherently influence a child’s social and spatial education. Toys are educational devices, representations of culture and ideology. The Playmobil® set glaringly identifies which core ideas of adult culture are to be passed down to the younger generation. A toy is a carefully curated representation of a real or fantasy world, which serves as a dissemination device for architectural and historical narratives. As Roland Barthes has explained, “toys always mean something, and this something is always entirely socialized, constituted by the myths or the techniques of modern adult life.”5 Toys translate imagery into physical objects designed for engagement and knowledge acquisition through the act of play. The sociologist Gilles Brougère further explains that for children, play is not limited to acts and objects bound by logic but rather allows the creation of images with a logic of pretending.6 Children are imitators, they will reproduce the scheme given to them.7 Playmobil® set no.9998 clearly evidences a connection between the transfer of adult spatial and racial dynamics into a child’s world. The Playmobil® set, akin to LEGO®’s equivalents, behaves as a historical and anthropological device within which we can read different architectural narratives.

“Timeless” and Insignificant

The Western architecture in both toy sets displays modernization and expansion, whereas the Indigenous people are portrayed as fixed in an obscure time period. It is alarming that even in the re-editions, these populations have neither enriched nor evolved and it remains geographically hard to decipher where these people belong. By never proposing the tipi as a structure that can be built, but as a ready-made complete element, the narrative of the insignificance of the building process is reinforced. By buying the complete no.9998 set, the child is urged to spend a greater amount of time erecting the infrastructures of the colonial oppressor. Interpreting the set’s staging of the individual parts, the importance is placed on the architectural elements of the white colonizer, emphasizing an architecture of violence and control. Indeed, the fortified structure of “Fort Glory” underlines that there is a clear spatial boundary between populations. Highly secured entry points thus filter who belongs and who doesn’t. The name of the fort itself implies a conflict and explicitly identifies the winner. Nationalistic symbols such as the flag and uniforms are central to the presentation of the set, while the presence of the tower reinforces surveillance as a tool of control over Indigenous populations.

Toys of Genocide. Icons of Colonialism.

There is no doubt that even a child of Indigenous descent would rather be a Playmobil cowboy and re-enact a war where the Indigenous populations are displaced. The colonial canon upholds white supremacy and Indigenous inferiority, feeding into fantasies of a superior race entitled to occupy all spaces. Indigenous scholars have addressed the coloniality and aggression embedded within cowboy and Indian toys. Scholar Michael Yellow Bird writes that “cowboys and Indians [symbolize] America’s past and current infatuation with colonization and genocide” which “create a subconscious desire to kill real Indians”.8 Today, white parents remain unconcerned by such imagery and vocabulary. Michael Yellow Bird urges us to view these as toys of genocide, as toys of supremacy and icons of colonialism. Indigenous culture is reduced to a caricature that distorts Indigenous past, present and future experiences. Indigenous populations, presented as unreasonable savages are outnumbered and readily defeated by cowboys who, despite their oppressive weaponry are portrayed as the heroes.

Status Quo

While the LEGO® set allows pieces to interchange, Playmobil®’s narrative is controlled by the manufacturer. This dynamism of LEGO®’s pieces does not insist on a single structural hierarchy but leaves that up to the user. In 2002, Tom Morton in Frieze Magazine wrote “Playmobil isn’t about… the limitless possibilities of Lego; it’s about the plastic preservation of the status quo”.9 One will however notice that LEGO® proposes a tipi as a mere accessory (Fig. 2), for it can’t be built by the child. These toys thus uphold systemic racism. The toys legitimize the idea that Indigenous populations can be removed from space. The mass production and popularity of these toys systemically supported the proliferation of this discourse. This narrative has even been exported to other countries due to the success of the toy. Playmobil® and LEGO®’s built an economic market that contributes to the material and cultural oppression of Indigenous populations through infantilization and misrepresentation. It is fraudulent to insinuate that all Indigenous people live remotely in depictions of deserts, which lack clear geographical references, therefore such toys romanticize a Eurocentric fiction of the past. One could argue that these toys, like Viking sets or Pharaoh and Pyramids, simply represent history, but solely representing Indigenous populations in the historical Western collection toy set frames their presence as a historical anecdote and refuses to acknowledge the multi-dimensional complex history of an entire culture. The re-edition (Fig. 5) of cowboys and “Indians” demonstrates absolutely no attempt to promote culturally accurate models. A systematic racial division and classification of space and architecture—of form, style, colour, materials—is still imposed. As if the tools, objects, and architecture were not enough to convey that the Indigenous populations did not belong, stereotyped physical features are accentuated: indeed the “Native Indian” figures were the only figures on which LEGO® has printed noses.

Geometry and Generalizations

The idea that such simplifications in the architecture and portrayal of standard elements were made to be better understood by children must be refuted. Indeed, countless western housing typologies, both ancient and modern, exhibit deeply nuanced and comprehensive architectures. For example, the Medieval Blacksmith (set. 6329) released in 2014, boasts minute architectural details and the house must be completely assembled for the enjoyment of the child. The White characters are presented in countless spaces and configurations further asserting that variety is possible.

We should also refute the idea that Indigenous architectural typologies are simplified because of the inherent cone-like and circular forms. Both LEGO® and Playmobil®’s catalogues showcase countless projects that disprove this supposed constraint. The Coliseum, for example, is built for assembly despite the circular architecture. While it could be argued that the toys represent the textile surfaces, there is precedent for fabric objects being offered as buildable elements, as with the 2020 Pirate sails (no. 31109). Furthermore, these toys convey numerous architectural inaccuracies and gross generalizations regarding the Indigenous cultures. Tipis and totem poles cultural forms from different native groups. The tipi was used by Plains groups of the Plateau region10 while totem poles were cultural traditions of the groups of a narrow strip on the Pacific Northwest coast.11 Mixing and homogenizing the diverse native heritages is another example of racist misinformation in media and popular images, further rendering invisible the existence of permanent villages, pit houses and wood frame structures.12 These toys influence racial and spatial thinking. While attempting to represent different architectural languages, they reinforce a dominant architectural language rooted in the coloniality of power. Colonization is founded on the forced erasures of tradition and culture. These toy sets, through mass production and dissemination, are tools employed to erase authentic Indigenous culture, prioritizing White architecture and existence. These toys evidence the systematic representation of Indigenous populations as physical obstacles to American progress. The cover of the Playmobil set places the Indigenous populations at the side, a mere obstacle in the path of thriving white men. Their displacement is implied as a necessary step in the heroic white Anglo-Americans conquest over savage, subhuman populations for the “greater good” of Americans.

Toys to Topple down and Figurines to move Forward

Unless we challenge the false histories conveyed through harmful representations of population hierarchies and dynamics through a concerted, collective endeavour, these toys will continue to legitimize the narrative of European colonialism, stereotyping Indigenous populations through the reduction of tipis, headdresses and tom-toms as toys. Companies like Playmobil® must immediately cease employing racist terms to refer to Indigenous People such as “Indians”, “American Indians” or “Native Americans”. While “Fort Glory” is no longer for sale, it has been replaced with “Fort Brave” still conveying cowboy heroism.

To counteract the paucity of non-white architectures deemed valuable, we must develop architectural pedagogies imbued with and inspired by decolonization. The popular corporate-driven narrative of Indigenous populations must shift to reflect the reality of their culture. Indigenous architecture and sacred cultural elements are not simply toys for white children. Neither LEGO® nor Playmobil® offers toys with slave boats or concentration camps, reflecting the widespread condemnation of such barbarous historical events. The glamorization of colonialism and the genocide of the Indigenous people in America apparently still leaves parents unoffended, and this must be addressed. Human history is arguably a long series of violent events. Perpetuating the erasure of oppressed cultures is certainly not the solution. Instead of reducing Indigenous architecture to a single tipi, these toy sets should include a diversity of representations. These toy manufacturers must expand their current canon of what they advertise as architecture. Today there is a tendency to create toys replicas of a specific building, architect or city. This is highlighted in LEGO® Architecture’s new series that reproduces architectural icons such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Falling Water” or Mies Van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and landmark cities, often emblems of Capitalism or icons of an antique empire. It is time to expand the educational applications of toys with diverse, rich and comprehensive knowledge.

--------------------------

Hermine Demaël wrote this essay for ARCH 355 in Winter 2021 while an undergraduate student at the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University.

--------------------------

1 International Work for Indigenous Affairs, “Indigenous People in the United States”, accessed March 27, 2021, https://www.iwgia.org/en/usa.html.

2 Bob Joseph, “21 Things You May Not Know about the Indian Act,” Indigenous Corportate Training Inc., accessed March 27, 2021, https://www.ictinc.ca/indian-act-art.

3 “Toy Town,” CCA, accessed March 23, 2021, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/events/2746/toy-town.

4 Danielle Barbosa Lins de Almeida, “On Diversity, Representation and Inclusion: New Perspectives on the Discourse of Toy Campaigns,” Ling. (dis)curso, Tubarão 17, no. 2 (May 2017): 257-270, https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4017-170206-6216.

5 Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Jonathan Cape (New York: The Noonday Press, Farrar, Straus & Girou, 1972), 53.

6 Martin Fournier, “A quoi sert le jeu ? Entretien avec Gilles Brougère," Sciences Humaines, no. 257 (March 2014): 8.

7 Wang Zhidan, Williamson Rebecca A., Meltzoff Andrew N., “Imitation as a mechanism in cognitive development: a cross-cultural investigation of 4-year-old children’s rule learning,” Frontiers in Psychology, volume 6 (2015): 256, https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00562.

8 Michael Yellow Bird, “Cowboys and Indians. Toys of Genocide, Icons of American Colonialism,” Wicazo SA Review, no. 19 (Fall 2004): 33-48.

9 Tom Morton, “ Plastic People,” Frieze, June 6, 2002, https://www.frieze.com/article/plastic-people.

10 Pauls, E. Prine. "Plateau Indian," Encyclopedia Britannica, November 11, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Plateau-Indian.

11 Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia, "Totem pole." Encyclopedia Britannica, March 18, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/totem-pole.

12 Heather Ramsay, “Totem Poles: Myth and Fact,” The Tyee, March 31, 2011, https://thetyee.ca/Books/2011/03/31/TotemPoles/.

Additional References:

Aisha Gani, “Playmobil accused of ‘perpetuating ugly stereotypes’ by UK parent,” The Guardian, October 9, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/09/playmobil-toys-accused-ste....

Arlene Hirschfelder, Paulette F. Molin, “I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans,” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, February 22, 2018, https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/native/homepage.htm.

Corey Snelgrove, Rita Kaur Dhamoon, Jeff Corntassell, “Unsettling settler colonialism: The discourse and politics of settlers, and solidarity with Indigenous nations”, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 3, no. 2 (2014): 1-32, https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/native/homepage.htm.

Jason Wilson, “The Playmobil Conundrum,” The New Yorker, October 9, 2015, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-playmobil-conundrum.

Kevin Gover, “Five Myths about American Indians,” The Washington Post, November 22, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths/five-myths-about-ameri....