Summertime means hammocks, BBQs, fireworks, and mosquito bites.

At least it does for me. Those rotten little suckers seem to just love me. They’ll flock to me even when there are three other people sitting in my backyard. What is it about my blood that they seem to enjoy so much?!

Let’s take a look at the science behind mosquitos and try to answer two questions: Why do mosquitos bite certain people, and what should we do to make them stop?

Take-home message:

- Blood type may or may not play a role in attracting mosquitos

- Products using DEET, icaridin, PMD, metofluthrin, and some blends of essential oils are effective at repelling mosquitos

- Bug zappers, sonic devices, citrosa plants, B vitamins, and scent-baited traps are not effective at repelling mosquitos and should be avoided

Mosquito isn’t a Species, it’s a Group

Before discussing the nitty-gritty of mosquito attraction, we need to realize something. While we tend to think of all flying bugs with proboscises as mosquitos, in truth there are more than 3500 species categorized into 112 genera that fall under the moniker of mosquito.

With such variation in species comes a lot of variation in habitats, behaviours, and risks. For instance, malaria is transmitted to humans only by mosquitos of the genus Anopheles, while yellow and dengue fever are transmitted by those in the genus Aedes. Canada is home to roughly 82 species of mosquitos belonging to the genera Anopheles, Culex, Aedes, Mansonia, and Culiseta. Some mosquitos are anthropophilic, meaning that they preferentially feed on humans, while others are zoophilic and preferentially feed on animals.

We’re typically taught to remove standing water from our property and avoid boggy or marshy areas (good luck in Ontario) to avoid mosquitos, but some species of these bugs don’t exclusively lay their eggs in water. We tend to think of mosquitos being at their worst in the summer, at dusk and dawn, but different species are active at different times, and their behaviour can even change from season to season, making it hard to predict when we are at risk of getting bitten.

Something that is true of all mosquito species though is that only the females bite. They require a blood meal in order to produce their eggs. The nasty by-product of this reproductive cycle is that they transmit diseases, and actually kill more people per year than any other animal.

How Mosquitos Track You

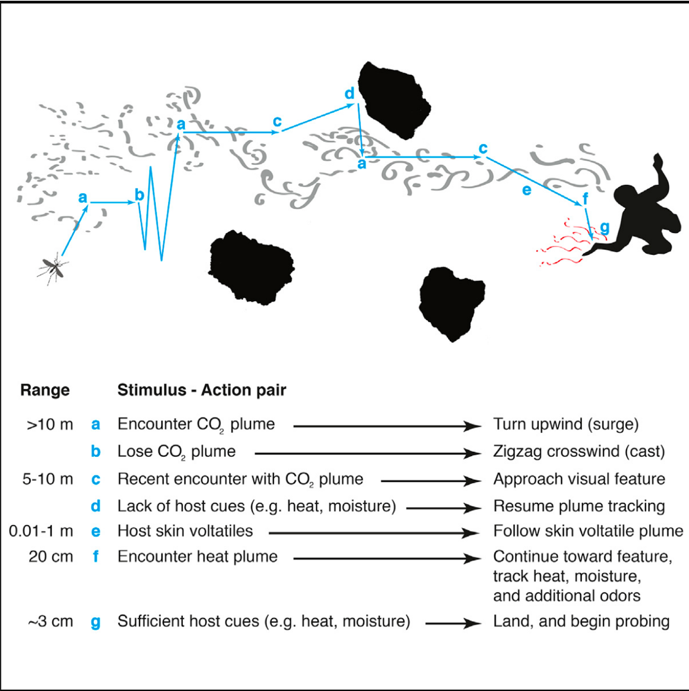

Mosquitos home in on their dinner-to-be by following a few different signals. The first clue that something biteable is nearby is the detection of a CO2 plume exhaled on the breath of mammals and birds alike.

The amount of CO2, however, does not affect the attractiveness of a specific target, so even if you’re a human who produces more CO2 than others (such as those who are larger or pregnant) that alone is not responsible for your irresistible-to-mosquitos aura. This makes sense since large animals like cows naturally produce much more CO2 than humans, yet many mosquito species still prefer to bite us.

Mosquitos will track a CO2 plume until they encounter host-cues. These first of these clues that a target is close by is usually smells emanating from the skin, which we’ll discuss more in a second. As they get close to the source of a smell, mosquitos will then detect and head towards heat and moisture signals emanating from a body.

We don’t know whether changes in body temperature affect how attractive you are to a mosquito, but we do know that sweating increases the volatile compounds on your skin that they love, and that anhidrotic people, or those who show decreased sweating, are less attractive to the pests.

The main mosquito-cues that can differ between humans are the olfactory ones. While it’s easy to swap your shampoo and soap for unscented varieties that won’t attract mosquitos like the sweet-scented ones do, a lot of the smells that mosquitos sense are innate to your physiology and sadly are not something that we can really change.

A few of these odorous chemicals include ammonia, lactic acid, sulcatone, and acetone. For many of these compounds, however, higher concentrations don’t equal greater mosquito attraction. Instead, they modulate the attractiveness of other substances. For instance, lactic acid has been shown to increase mosquitos attraction to ammonia and CO2.

While an animal may produce similar-to-human levels of CO2, humans tend to produce more lactic acid than primates or cows. This lactic acid synergistically increases the appeal of CO2for anthropophilic mosquito species, while actively dissuading zoophilic species from landing on you. Conversely, ruminants like cows also exhale1-octen-3-ol, a substance that attracts zoophilic species of mosquitos. In a demonstration of this, skin rubbings taken from cows were made just as attractive to anthropophilic mosquitos as skin rubbings from humans via the addition of lactic acid.

The Role of Blood Type

There has been significant debate over the role blood type plays in attracting mosquitos. Initially, a 1972 study using Anopheles gambiae found that mosquitos preferred those with O type blood (O>B>A>AB). But a 1976 study using the same mosquito species did not confirm this.

A 1980 study examined 736 patients and found that while those with A type blood made up 17.6% of the control group, they made up 29% of the malaria cases. Conversely, those with type O blood made up 33% of the control group but only 22% of the malaria cases. While this alone does not tell us whether or not certain blood types are more likely to be bitten by mosquitos or contract malaria, it does point to blood type playing some role in mosquito attraction.

Some clarity came with a 2004 study done with Aedes albopictus that found a similar pattern to the original 1972 study: O>B>AB>A. The researchers also compared the mosquito-attracting ability of those who secrete substances corresponding to their blood type onto their skin, versus those who do not. Their theory was that these blood type-specific secretions could explain mosquito’s ability to find their preferred type O prey. Their results, however, showed an order of preference of O secretors>A nonsecretors>B secretors>O nonsecretors>A secretors>AB secretors>B nonsecretors, which do not correspond to the blood type preferences established.

Concerning blood type’s role in attracting mosquitos, we’re stuck with the often-written phrase more research needed. Given the conflicting results and relatively small sample sizes of these studies, we cannot make definitive conclusions. Not to mention that we have no idea how mosquitos are able to detect a target’s blood type from a distance.

If mosquitos do truly target those with type O blood, the authors of this study theorize that preference could have evolved due to the prevalence of type O blood in African nations. The three most populous African nations are Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Egypt, and the percentage of their populations with type O blood are 51.3%, 39.0%, and 52.0% respectively.

How to Avoid Getting Bitten

Anyways, even if we knew what blood types attract mosquitos, you can’t change your blood type. So, what can you do to get some relief from these minuscule menaces?

First, it’s important to remember that just because you’re not forming welts doesn’t mean you’re not getting bit. Not all bites will lead to the familiar welts, so even if you’re not covered in itchy bumps, if you’re near mosquitos you should be using repellant.

Things That Work

Physical barriers should be your first line of defence against mosquito bites. Install screens on your windows, doors, tents, and RVs, and cover children’s cribs, playpens, and strollers with fine mesh to keep mosquitos out.

You can get specialty meshes and clothing treated with permethrin, an insecticide, for adults in Canada. The anti-mosquito effects of the chemical will last through several wash cycles, but permethrin-treated objects should never be used for or around children, including screens or mosquito nets that they may interact with, as their safety has not been evaluated.

In general, you should strive to wear light coloured clothing, and cover as much of your skin as the heat will allow. Mosquitos are better able to orient themselves towards darker targets, so skip the Nirvana t-shirt and try on a white tee instead.

Flowery and fruity scents will attract mosquitos greatly since they feed on flower nectar (in addition to us) but even non-botanical scented products should be avoided whenever possible. This includes (amongst many others): shampoo, soap, conditioner, shaving cream, aftershave, perfume, deodorant, hand cream, makeup, and even laundry soap and softener.

In terms of repellants, the good news is that you have more options on the market than ever. The bad news is that only some of them work.

DEET

N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide, better known as DEET, has been the standard ingredient in commercial bug sprays since 1957 when it made the jump from military to civilian applications. While it used to be thought that DEET interfered with a mosquito’s ability to detect lactic acid, more recent research has found that mosquitos detect and avoid DEET directly. Much like I do with vinegar.

Misguided fears about DEET’s safety have spurred some to move towards other mosquito repellants, and while there are other effectual repellants, none work as well or for as long as DEET. In terms of its safety, DEET has been more thoroughly studied than any other repellant and when used according to guidelines is quite safe.

When utilizing DEET-based repellants it’s important to pay attention to the concentration of DEET in the product. The Government of Canada recommends that no concentration over 30% be used on anyone and that only formulations containing up to 10% be used on children aged two to twelve (up to three daily applications) and aged 6 months to 2 years (only one daily application). Babies under 6 months should be kept mosquito-bite free through the use of nets and screens rather than repellants of any type.

Icaridin

Icaridin, also known as picaridin, is a safe alternative to DEET popular in Europe and recommended by the Government of Canada for use against mosquitos and ticks on anyone over the age of 6 months. This study showed that products with 9.3% icaridin can repel mosquitos for up to 3 hours, while this study showed that a 10% concentration repelled mosquitos for more than 7 hours. This is comparable to the 5 to 7+ hours of protection provided by 7-15% DEET products, although DEET has been more widely studied. Contrarily this study found a 10% icaridin repellant rather ineffective. If you find them effective, icaridin-based products could be particularly useful for small children who have exceeded their daily recommended applications of DEET-based products but still need to remain outside.

Citronella

Citronella has long been the standard of backyard BBQs and picnics in its candle form, but in addition to the coils and candles designed to keep mosquitos out of a particular area, there are also repellants that contain citronella oil.

Citronella oil is made mostly from 2 species: C. nardusand C. winterianus, and contains many different chemicals, the most notable in terms of their insect-repelling nature include camphor, eucalyptol, eugenol, linalool, geraniol and citronellal.

While it’s citronellal that provides the flowers with their characteristic lemony scent, a 2008 study’s findings suggest that it is actually linalool and geraniol that provide the bug-repelling effects. The researchers compared candles made of 5% citronella, linalool, and geraniol, and found the geraniol and linalool candles much more successful at repelling mosquitos than normal citronella (85% and 71% versus 29% repellency rates over 3 hours). This study likewise confirmed straight citronella candle’s inability to effectively repel mosquitos alone.

This study examined three mosquito repellants that contained citronella and found them all significantly less effective than formulas containing DEET or icaridin, and this study examined 3 wearable bracelets that claimed to emit geraniol and found them as effective as using no repellant at all.

So while it could be useful to burn a geraniol or linalool candle while you’re sitting outside, you should probably still backup your protection with an effective repellent.

P-Menthane-3,8-diol (PMD)

Products with p-Menthane-3,8-diol, a chemical found in small amounts in oil extracted from the lemon eucalyptus tree, have generally (studies 1,2,3) show it to be as effective as DEET and icaridin. The Canadian government recognizes PMD’s repellency effects on blackflies and mosquitos but recommends against using PMD-containing products on anyone younger than three.

Soybean and Essential Oils

Soybean oil is perhaps the strangest bug-repelling ingredient on this list, but repellant formulations containing mixes of soybean oil and various essential oils have been rapidly making their way onto the Canadian market. While the soybean oil itself does not repel mosquitos, it works in tandem with the essential oils also included in the repellants to stabilize their volatility.

This study found that a formulation including soybean oil, coconut oil, geranium, and vanillin repelled mosquitos for more than 7.2 hours. However, the same study, and another, showed that other formulations also containing soybean oil, as well as other various essential oils (menthol, eucalyptus, lavender, rosemary, sage, etc.) worked very minimally.

This points to the particular essential oils and other ingredients in the repellant making the difference rather than the soybean oil itself. This makes sense when you consider that the geranium included in the effective soybean repellant was likely citronella, and that vanillin has been shown to increase the repellency effects of citronella.

The Government of Canada doesn’t place any age restrictions on formulas containing soybean oil but recommends not using essential oil formulations on those younger than 2. So, you’re free to experiment with different products using different ingredient blends and see which works, but make sure to turn to something a bit more reliable when actually venturing into the woods.

Metofluthrin

If you’d rather wear a clip-on device than use a mosquito repelling lotion or spray, your only good option is those that emit metofluthrin. This 2017 study examined the efficacy of 5 wearable anti-mosquito devices and found that only the metofluthrin at a concentration of 31.2% effectively repelled mosquitos. Much like citronella candles, however, clip-on devices work by creating a fog of mosquito-repelling chemicals around you. This means that they will only be effective for times when you’re sitting still.

Things That Don’t Work

While components of citronella oils may be effective repellants, citrosa houseplants are not. Nor are the sonic mosquito repelling products that claim to play sound at frequencies that will drive mosquitos away. I’ll let the authors of this paper sum up the evidence for these products: “We are not aware of any scientific study showing that mosquitoes can be repelled by sound waves and therefore we consider these devices as the modern equivalent of snake oil”.

While synthetic mosquito lures that attract the bugs just as well, if not better, than humans have been developed, in practice mosquitos continue to be attracted to humans even when these devices are used. Thus, their use is not recommended by the Canadian Government. Likewise, handheld or mounted bug zappers certainly exist and can be quite satisfying to use for revenge on the bugs that stole your blood, relying on them for protection is not a good idea.

You may have heard that eating bananas can alternatively make mosquitos more or less attracted to you. The claims of banana’s repelling power stem from their high vitamin B6 content, but a 2005 study tested the effects of vitamin B consumption on mosquito attraction and found absolutely no effects. In terms of bananas attracting power, those claims come from octenol content, a chemical that does indeed attract mosquitos. But, octenol isn’t unique to bananas, it’s found in many foods, and no studies have been done that prove consuming bananas does make you a bug-target, so keep on munching.

A subtler mistake you may make when selecting your mosquito repellant is to use a product that combines sunscreen and bug spray. While certainly convenient, the problem lies in sunscreen’s need to be reapplied much more frequently than mosquito-repellants. If both products are needed for an outing, it’s recommended that you wait 20 minutes between applying sunblock and repellant.

Basically, to avoid being a mosquito-target you should stay as scent-free as possible, wear light clothes, avoid bogs and use an effective repellent (such as those containing DEET or icaridin). Or, you could always stay inside- I hear its quite nice this time of year.

Want to comment on this article? View it here on our Facebook page!