In 1843 a letter to the editor entitled “The growth of the beard medically considered” published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal argued that beards were medicinally beneficial, and that “the practice of shaving the beard, and thus depriving the face, throat and chest of that efficient protection which nature has provided” was responsible for the “numerous diseases of the respiratory organs with which mankind are afflicted.”

Yet, by 1916 beards had lost their safeguarding status. Edwin F. Bowers (who would go on to invent the pseudoscience of reflexology) wrote in an article for McClure’s Magazine that “there is no way of computing the number of bacteria and noxious germs that may lurk in the Amazonian jungles of a well-whiskered face, but their number must be legion.”

It was only two years later that the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic hit, and any possible disease vector, including beards, was targeted in bids to quell the number of sick individuals. Given that we’re currently in the midst of what the United Nations is calling “a global health crisis unlike any” it seems inevitable that beards once again fall under the literal microscope as potential germ gardens.

Luckily, given the scientific advances that have taken place since the last few hundred years, we don’t need to rely on racially contentious observations like this one from 1843: “those nations where the hair and beard are worn long, they are more hardy and robust and much less subject to diseases, particularly of a pulmonary character, than those who shave.”

Let’s see what science has to say about how pathogenic your facial hair might be.

Does facial hair collect more germs than a smooth face?

The real question of hair’s cleanliness isn’t whether or not it can harbour microbes. Unfortunately, just like any other surface, it most certainly can. What we really care about is whether a beard contains more germs than a clean-shaven face.

A 1967 study saw four volunteers’ beards or clean-shaven faces sprayed with a bacterial solution and swabs taken from their skin 30 minutes and six hours after, either with or without letting them wash their faces with soap. They found that while there were more bacteria on clean-shaven faces than on beards before washing, more bacteria were removed by washing a clean-shaven face compared to washing a beard. So even though the beards didn’t accumulate more bacteria than the face, they did retain it through the wash.

A 2014 study reinforced the finding that facial hair doesn’t accumulate more bacteria than non-hairy facial skin. Researchers took swabs from the cheeks and upper lips of 199 healthcare workers who had facial hair and 209 who didn’t. The results showed that clean-shaved healthcare workers were actually more likely to harbour certain types of bacteria than their fur-faced coworkers. Similarly, a 2015 study of 118 mustachioed and 123 non-mustachioed men found that “nasal S. aureus [a bacterium] carriage is similar in men with and without a mustache."

So even though beards may retain bacteria through a wash (highlighting the importance of washing your beard well), there’s no evidence that they accumulate or harbour larger bacterial populations than smooth faces.

Does facial hair spread more germs than a smooth face?

The other piece of this facial hair puzzle is whether or not people with beards spread more microbes than those without. This question has been at the forefront of a debate over whether or not doctors, nurses, surgeons and other healthcare workers should be allowed to have facial hair. Some people fear that their beards and mustaches could be contaminated and lead to infected patients. Others worry that strict facial hair rules unnecessarily limit a doctor’s personal choices.

Part of why this debate rages on is due to some conflicting study results. A study published in 2000 by McLure et al. compared the bacterial shedding of 10 bearded, 10 clean-shaven and 10 female subjects. The researchers had the volunteers wear a surgical mask either while talking and moving their faces such that the mask “wiggled” around or while still. They held agar plates just below their chins to collect any bacteria that fell off and then cultured these colonies and quantitated them. The results showed that with or without mask wiggling, bearded subjects shed more bacteria than clean-shaven ones.

However, a 2016 study by Parry et al. using the same methods found no difference in the amounts of bacteria shed by bearded versus clean-shaven subjects regardless of whether they wore a surgical mask, a surgical mask plus a hood (shown below), or nothing.

Image source: http://www.healio.com/doiresolver?doi=10.3928/01477447-20160301-01

Unfortunately, this leaves us at the familiar scientific dead-end: more research is needed. Without another study, preferably one with a much larger sample size than the 30 and 20 of these trials, it’s difficult to know which results to trust. Both researchers present reasonable explanations for their results. McLure et al. suggest that beards “may act as a reservoir for bacteria and dead organic material which can be easily dislodged with movement of the face mask,” whereas the daily act of shaving helps to remove the “superficial layer of skin containing bacteria” and thus give clean-shaven men fewer microbes to shed.

On the other hand, Parry et al. suggest that daily shaving can cause micro-cuts on the face that can serve as hiding places for bacteria. They also pondered if their results could be due to beard lengths. They showed that longer beards shed less than shorter beards when the subjects wore masks and hoods, which they hypothesize is due to longer beard hair being less abrasive and therefore leading to fewer shed bacteria. Unfortunately, since McLure did not report their participants’ beard lengths, it’s not possible to know for sure.

But wait, what about viruses?

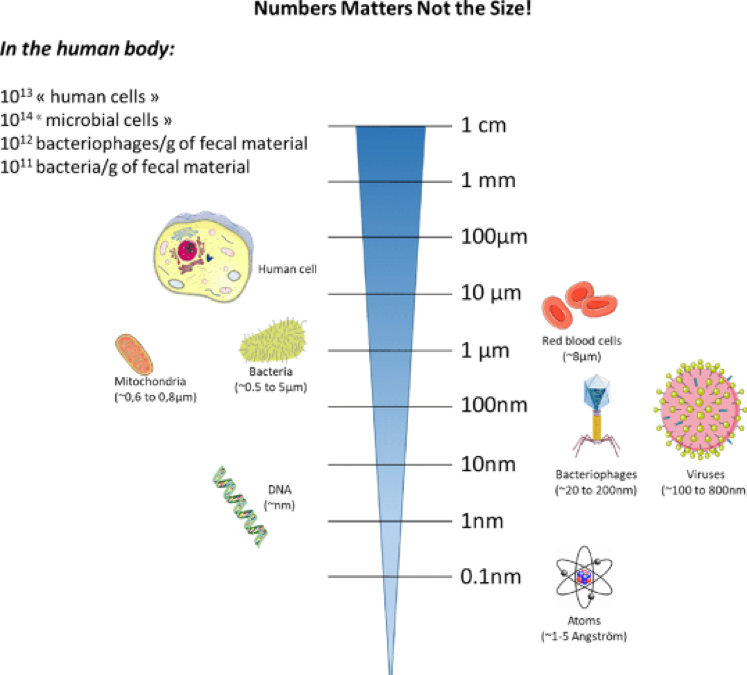

To throw another wrench in the interpretation of these results, allow me to point out that all these studies measured the amounts of bacteria on participants’ faces or beards. However, the current COVID-19 pandemic is being caused by a virus, not a bacterium. While this distinction may not seem important, there are a lot of differences between these two types of microbes: in particular, size! As you can see below, the size range for bacteria is roughly 500-5000 nanometres, but for viruses is only roughly 100-800 nanometres, making them quite a bit smaller. The SARS-CoV-2 virus (at the time known as 2019-nCoV) has been reported to be 60-140 nm in diameter, making it a particularly small virus, as viruses go.

In the end, there’s no compelling evidence that beards foster bacteria, but we cannot really say if they do lead to increased bacterial shedding. And as far as viruses are concerned, we have no evidence at all.

The good news is, that if you’re practicing proper social distancing, washing your hands often and not exposing yourself to others unnecessarily, you and your beard are unlikely to encounter the SARS-CoV-2 virus at all. So, if you’re doing your part to flatten the curve by staying home, keeping your beard should be fine. However, healthcare workers should consider the role that their facial hair may play in transmitting microbes and take care to wash it very thoroughly whenever possible. However, I do expect that, given that many facial hairstyles can interfere with special masks called respirators, many have already done a spring shave.

Image source: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/FacialHairWmask11282017-508.pdf

Leave a comment!