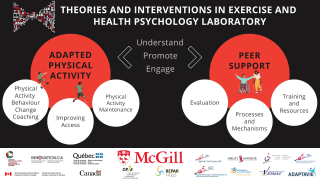

Research Areas

Stream 1: Adapted Physical Activity

Dr. Sweet and his team demonstrated that engagement in physical activity programs can help individuals with a physical disability participate in daily (e.g., cooking, self-care) and social (e.g., volunteering, meeting with friends) activities [1, 2, 3]. However, barriers to physical activity participation persists for people with a physical disability. Accessing physical activity opportunities is therefore a challenge. Dr. Sweet and his team of undergraduate and graduate students and community-based partners showed that access to physical activity opportunities is a result of the interaction between infrastructure, social interactions, and policies/public services [4]. As a result of this study, his team led one of the few studies that focused on identifying solutions to counter the many barriers to physical activity among people with a physical disability [5].

Dr. Sweet and his team have begun testing solutions to enhance physical activity opportunities among persons living with a physical disability:

1) Increasing Physical Activity Opportunities through tele-health interventions

Increasing physical activity opportunities through tele-health interventions among people with spinal cord injury (SCI; [3, 6]) and lung disease (Michalovic, PhD thesis (2021); Osborne, Master’s (2022).

2) Enhancing training to kinesiologist working in disability community organizations

Dr. Sweet and his community-based partners co-wrote an applied book chapter on how kinesiologists can assess, prescribe, and motivate physical activity among people with spinal cord injury in a kinesiologist guidebook for adapted physical activity [7]. Most recently, Dr. Sweet and his community-based partners co-designed a project to create, deliver, and test a new kinesiologist training program on approaches to promote and prescribe physical activity among people with a physical disability (Sadaawi, Master’s thesis).

3) Increasing physical activity opportunities a the local context

In response to another of Dr. Sweet’s recommendations to increase physical activity opportunities at local context [5], Dr. Sweet worked alongside McGill’s Student Accessibility and Achievement Office and later Equity Office to develop Fitness Access McGill. Fitness Access McGill is a program that helps and supports McGill students and staff with a physical disability, chronic illness, or other impairments access physical activity opportunities.

Dr. Sweet and his team’s current research in adapted physical activity examines:

1. The use and coaching of physical activity behaviour change techniques among university students with physical disability or chronic conditions;

2. The conceptualization of physical activity maintenance among adults with physical disability.

Stream 2: Spinal Cord Injury Peer support

Only a few years ago, peer support research within a SCI context was at its infancy. Through his pan-Canadian peer support community-university partnership, Dr. Sweet propelled SCI peer support research forward by:

1) Identifying the most important outcomes for SCI peer support

Dr. Seet and his team has identified up to 87 outcomes that were related to SCI peer support [8; 9]. To render this list of outcomes realistic for community-based organizations to use, two studies using community-based consensus methodology identified 20 outcomes as being the most important for SCI peer mentees (i.e., individuals who receive peer support) [10].

2) Creation of SCI peer support evaluation toolkit

With the in-depth understanding of the outcomes of peer support, Dr. Sweet and his team developed a new evaluation survey for SCI community-based organizations following a multiple step process for outcome identification. They are currently collecting data on the validity and reliability of this evaluation survey prior to making it freely available. Simultaneously, Dr. Sweet’s team is co-creating and testing a SCI peer support evaluation toolkit. This toolkit will assist community-based organizations select outcomes and custom build a survey to evaluate their SCI peer support programs. The survey and toolkit are in the final phase of testing.

3) Understanding of peer support program components

Dr. Sweet’s research has also provided insights into the key features of peer support programming which include high quality mentor characteristics [18, 19], program considerations [18, 20], and mentor-mentee interactions [10, 21]. These program features provide guidance on how to build SCI peer support programming, an area of research that has largely been ignored.

Dr. Sweet’s current research in spinal cord peer support examines:

1. Implementation of the SCI peer support evaluation toolkit within community-based SCI organizations, and

2. Co-developing and testing resources to develop and optimize SCI peer support delivery.

Citations

Underlined co-authors are TIE lab current or past members; italics are community partners

[1] Sweet, S.N., Donkers, S.J., Martin Ginis, K., Cao, P., McIntyre, A., Tomasone, J.R. (2023). Physical Activity Following Spinal Cord Injury: Psychosocial Outcomes. In Eng JJ, Teasell, R.W., Miller, W.C., Wolfe, D.L., Townson, A.F., Hsieh, J.T.C., Connolly, S.J., Noonan, V.K., Loh, E., Sproule, S., McIntyre, A., Querée M., editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 7.0. Vancouver: p 1- 60

[2] Sweet, S. N., Shi, Z., Rocchi, M., Ramsay, J., Pagé, V., Lamontagne, M.-E., & Gainforth, H. L. (2021). A longitudinal examination of leisure-time physical activity (LTPA), participation, and social inclusion upon joining a community-based LTPA program for adults with physical disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 102, 1746 - 1754. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.02.025

[3] Chemtob, K., Rocchi, M., Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K., Kairy, D., Fillion, B., & Sweet, S. N. (2019). Using tele-health to enhance motivation, leisure time physical activity, and quality of life in adults with spinal cord injury: A self-determination theory-based pilot randomized control trial. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 43, 243-252. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.03.008

[4] Bonnell, K., Michalovic, E., Koch, J., Pagé, V., Ramsay, J., Gainforth, H. L., Lamontagne, M.-E. & Sweet, S.N. (2021). Physical activity for individuals living with a physical disability in Quebec: Issues and opportunities of access. Disability and Health Journal, 14, 101089. DOI: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101089

[5] Herbison, J., Osborne, M., Anderson, J., Lepage, P., Pagé, V., Levasseur, C., Beckers, M., Gainforth, H.L., Lamontagne, M-E., & Sweet, S.N.(2023). Strategies to Improve Access to Physical Activity Opportunities for People with Physical Disabilities. Translational Behavioral Medicine.

[6] Rocchi, M., Robichaud Lapointe, T., Gainforth, H., Chemtob, K., Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K., Kairy, D., & Sweet, S. N. (2021). Delivering a tele-health intervention promoting motivation and leisure time physical activity among adults with spinal cord injury: An implementation evaluation. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 10, 114–132. DOI: 10.1037/spy0000207

[7] Sweet, S. N., Levasseur, C., Michalovic, E., Pagé, V., & Lepage, P. (2020). Lésions médullaires et activités physiques adaptées. In C. Maiano, O. Hue, G. Moullec, & V. Pepin (Eds.), Guide d’intervention en activités physiques adaptées à l’intention des kinésiologues. Les Presses de l’Université du Québec.

[8] Rocchi, M. A., Shi, Z., Shaw, R. B., McBride, C. B., & Sweet, S. N. (2022). Identifying the outcomes of participating in peer mentorship for adults living with spinal cord injury: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Psychology and Health, 37(4), 523-544. DOI:10.1080/08870446.2021.1890729

[9] Sweet, S. N., Hennig, L., Shi, Z., Clarke, T., Flaro, H., Hawley, S., Schaefer, L, & Gainforth, H. L. (2021). Outcomes of peer mentorship for people living with spinal cord injury: Perspectives from members of Canadian SCI community-based organizations. Spinal Cord, 58, 1301-1308. DOI: 10.1038/s41393-021-00725-2

[10] Shi, Z., Michalovic, E., McKay, R., Gainforth, H. L., McBride, C. B., Clarke, T., Casemore, S., Sweet, S. N. (2023). Outcomes of Spinal Cord Injury Peer Mentorship: A community-based Delphi consensus approach. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 66, 101678. DOI: 10.1016/j.rehab.2022.101678

[11] Sweet, S. N., Hennig, L., Pastore, O., Hawley, S., Clarke, T., Flaro, H., Schaefer, L, & Gainforth, H. L. (2021). Understanding peer mentorship programs delivered by Canadian SCI community-based organizations: Perspectives on mentors and organizational considerations. Spinal Cord, I59, 1285-1293. DOI: 10.1038/s41393-021-00721-6

[12] Gainforth, H. L., Giroux, E., Shaw, R., Casemore, S., Clarke, T., McBride, C., Garnett, C., & Sweet, S. N. (2019). Investigating characteristics of quality peer mentors with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 100, 1916-1923. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.04.019

[13] Shaw, R., Sweet, S. N., McBride, C. B., Adair, B., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2019). Operationalizing the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to evaluate the collective impact of autonomous community programs that promote health and well-being. BMC Public Health, 19, 803. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-019-7131-4

[14] McKay, R. C., Giroux, E., Baxter, K., Casemore, S., Clarke, T. Y., McBride, C. B., Sweet, S. N., Gainforth, H. L. (2022). Investigating the Peer Mentor-Mentee Relationship: Characterizing Peer Mentorship Conversations Between People with Spinal Cord Injury. Disability and Rehabilitation. DOI: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2046184

Pillars of Research

Pillar 1: Understand

It is critical to understand the underlying concepts that predict physical activity and well-being before attempting to promote these outcomes. As a result, the focus of this pillar is to understand the psychosocial factors that predict physical activity and/or well-being. Research within each of the physical activity or well-being streams has been grounded in theory such as self-determination theory, self-efficacy theory and the health action process approach. The research consists of cross-sectional, prospective and experimental quantitative studies aimed to identify predictors of physical activity/well-being and qualitative studies that obtain the perspectives of specific groups on physical activity/well-being.

Examples of ongoing studies:

Physical activity stream: (a) Psychosocial predictors of physical activity for individuals who have completed cardiac rehabilitation; (b) Testing self-determination theory concepts in a set of experimental lab-based exercise studies.

Well-being stream: (a) Examining the role of spinal cord injury peer mentors on enhancing the lives of fellow peers with spinal cord injury; (b) Investigating the intersection between physical activity and eudaimonic (e.g., meaning) and hedonic (e.g., life satisfaction) well-being among cardiac rehabilitation participants. (c) Understanding social participation (i.e., engagement in daily and societal tasks) levels of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

Pillar 2: Promote

Pillar 2 focuses on promoting behaviours and enhancing well-being outcomes. Research within Pillar 2 can be informed from Pillar 1 studies or designed based on theoretical frameworks. In this pillar, promotion refers to any action taken to change behaviour or cognitions and has been organized by two streams: Persuasive messaging and intensive interventions.

Examples of ongoing studies:

Persuasive messaging stream: (a) Testing and comparing messages to reduce sedentary behaviour and increase physical activity; (b) Evaluating messages to promote physical activity action planning among inactive adults.

Intensive interventions stream: (a) A pilot randomized controlled trial on testing a self-determination theory-based tele-health intervention among adults with spinal cord injury.

Pillar 3: Engage

The engagement of consumers has become an integral part of research. Note that I am using the term “consumer” to represent any segment of the population that can (1) inform research, and (2) apply and use research findings which include all citizens, whether they are patients, healthy individuals, community organizations, researchers and/or health professionals. Therefore, this pillar focuses on two streams: consumer engagement and knowledge translation research.

Examples of ongoing studies:

Consumer engagement stream: (a) Examining the research and health care priorities of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; (b) Obtaining the perspectives of spinal cord injury peer mentors and mentees on the importance of peer mentorship on their lives.

Knowledge translation research stream: In collaboration, evaluate (a) the Active Living Leaders Program, a Canada-wide physical activity training program for adults with a disability and (b) Praxis 2016, an international conference aimed to bridge knowledge translation gaps in spinal cord injury using the RE-AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance).