Charles Boberg, Claire Henderson, and Jackson Mundie

A full analysis of the responses to The New Survey of Canadian English is still in progress, but interim results are now available and are presented and analyzed below. A final version of the results and analysis will appear soon in journal articles that are now in preparation. This page was last updated on April 22, 2024.

In keeping with the main goal of the project, the following analysis focuses first on a comparison with the study that inspired it: the original Survey of Canadian English, published in 1972 by M.H. Scargill and H.J. Warkentyne (see also Warkentyne 1971). Some of these comparisons can also extend to an even earlier survey of Ontario English conducted by Walter Avis in the mid-1950s (Avis 1954-1956), or with the more recent Dialect Topography research of J.K. Chambers and several of his colleagues in the 1990s (presented, e.g., in Chambers 1998, 2000, 2007, or online). Several other earlier studies can also be consulted for comparative quantitative data on some of the variables in particular regions: see Gregg et al. (2004) for Vancouver; Nylvek (1992) for Saskatchewan; Woods (1999) for Ottawa; De Wolf (1992) for a comparison of Vancouver and Ottawa; and Hamilton (1958) for Montreal.

The analysis then turns to regional and age-based variation in the new 2024 data, including a set of new vocabulary questions, which were reprised from the North American Regional Vocabulary Survey and related research of Boberg (2005, 2010, 2016); some of these also appear in Chambers’ work. Other aspects of the new data, such as regional variation below the provincial level, will be examined more extensively in subsequent publications.

References:

- Avis, Walter S. 1954–1956. Speech differences along the Ontario–United States border. Journal of the Canadian Linguistic Association 1/1: 13–18 (Vocabulary); 1/1 (Regular Series) 14–19 (Grammar); and 2/2: 41–59 (Pronunciation).

- Boberg, Charles. 2005. The North American Regional Vocabulary Survey: New variables and methods in the study of North American English. American Speech 80/1: 22-60.

- Boberg, Charles. 2010. The English Language in Canada: Status, History and Comparative Analysis. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Boberg, Charles. 2016. Newspaper dialectology: Harnessing the power of the mass media to study Canadian English. American Speech 91/2: 109–138.

- Chambers, J.K. 1998. Social embedding of changes in progress. Journal of English Linguistics 26/1: 5-36.

- Chambers, J.K. 2000. Region and language variation. English World-Wide 21/2: 169–199.

- Chambers, J.K. 2007. Geolinguistic patterns in a vast speech community. Linguistica Atlantica 27: 27-36.

- De Wolf, Gaelan Dodds. 1992. Social and Regional Factors in Canadian English. Toronto: Canadian Scholar’s Press.

- Gregg, R.J., et al. 2004. The Survey of Vancouver English: A Sociolinguistic Study of Urban Canadian English. Occasional Papers No. 5. Kingston, ON: Strathy Language Unit.

- Hamilton, Donald E. 1958. Notes on Montreal English. Journal of the Canadian Linguistic Association 4/2: 70–79.

- Nylvek, Judith Anne. 1992. Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions. Doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria.

- Scargill, Matthew Henry, and Henry J. Warkentyne. 1972. The Survey of Canadian English: A report. English Quarterly 5/3: 47-104.

- Warkentyne, Henry J. 1971. Contemporary Canadian English: A report of the Survey of Canadian English. American Speech 46/3–4: 193–199.

- Woods, Howard B. 1999. The Ottawa Survey of Canadian English. Kingston, ON: Strathy Language Unit, Queen’s University.

Citation and use

The data and analysis on this site/page can be cited as: Charles Boberg, Claire Henderson and Jackson Mundie (2024). New Survey of Canadian English: Results. URL: https://www.mcgill.ca/canadianenglish/results. They should not be reproduced without the permission of the authors.

The Sample

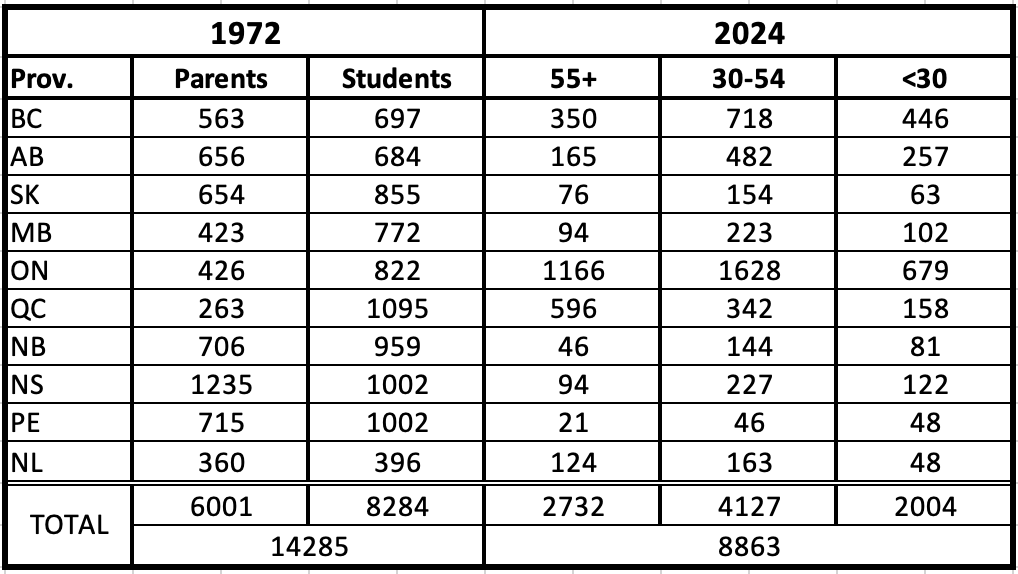

Since it was launched in the summer of 2023, the online survey has received 13,275 responses, just short of the 14,228 responses reported in the original survey. This is a notable achievement and our thanks go out to all the people whose participation made it possible: both individual respondents across the country and academic, government, institutional and media colleagues who helped recruit respondents in each region. The vast majority of the responses are from Canada, but the dataset also includes about 200 responses from the United States and 40 from the United Kingdom (most of these from Canadians living abroad), with a few from other countries. The results below focus on the Canadian responses.

To allow a comparison with the original study, the Canadian responses have been classified by province (a disappointingly small number of responses from Canada’s three northern territories, which were not included in the 1972 study, are therefore set aside in this analysis). The original study gives very little information about its participants: its results tables indicate only their province of residence, sex and age, the latter a generational division between students in Grade 9 English classes, who would mostly have been 14 years old, and their parents. To make the new regional analysis as informative as possible, for purposes of the present analysis the new dataset has been restricted to those respondents who are native speakers of Canadian English and who still live in the province where they grew up. This criterion substantially reduces the total sample to 8,863 responses, but also reduces the influence of international and interprovincial migrants on the regional patterns, making them more closely reflective of local speech. Responses from people who now live in a different province from where they grew up have been retained for future analyses that examine Canada as a whole and the linguistic effects of migration, an important factor in a highly mobile population like Canada’s.

The new sample also comprises a much wider age range than the students and parents of 1972 and has therefore been divided into three age groups: those 55 and older, those 30-54 years old and those under 30. A comparison of the oldest group with the original study indicates whether the speech of the 1972 generations has changed over the last five decades; a comparison of the youngest group with the original study, especially with the students, indicates how youth speech has changed since 1972. A comparison of the two samples is shown below.

Highlights

The new survey reprised 50 of the original survey’s questions, focusing on those with the most enduring relevance today, and added 35 new questions, a few from Avis’ early survey and a few brand new variables, but mostly reprised from the North American Regional Vocabulary Survey (Boberg 2005, 2010). With 85 questions to analyze, the most important patterns of variation can easily get lost in a sea of details. To avoid that problem, following is a list of the ten variables that show the biggest differences between 1972 and 2024, presented in the order in which they occur on the survey. In this first list we focus on nationwide data, reflecting a national mean of the response frequencies from each of the ten provinces. Regional variation among provinces and variation among age groups in the new dataset will be examined in subsequent top-ten lists, below. The discussion will sometimes refer to the British and American standards, to which Canadian English can be compared. For this purpose, we take The Concise Oxford Dictionary, Ninth Edition as indicative of Standard British English and Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition as indicative of Standard American English, hereafter Oxford and Webster. To see the table of data associated with each variable, click on the plus symbol (+) next to the question text; click again to make the table disappear.

1972-2024 comparison

P5. Does genuine rhyme with fin or fine?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 53, Q26)

British and American dictionaries agree that genuine normally rhymes with fin, but only Webster acknowledges the pronunciation rhyming with fine as an alternate form. Avis reports about a third of his Ontario respondents using the fine variant (1956:47), but this increases to the majority of Canadians, especially in Western Canada, by 1972 (53, Q26), with only a quarter using the standard fin form. This distinctive pattern is now fading quickly: use of the fin form increases in the 2024 data, from just over half of the oldest respondents to 84% of the youngest, only 6% of whom still rhyme genuine with fine.

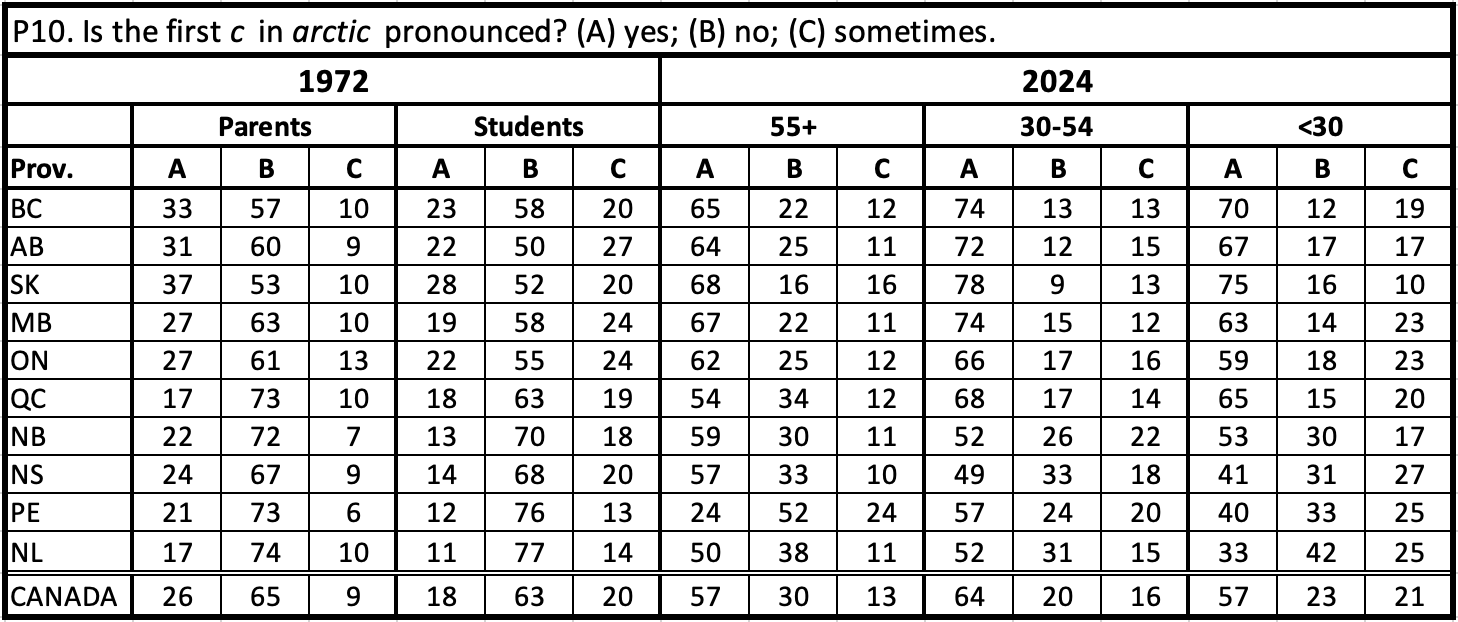

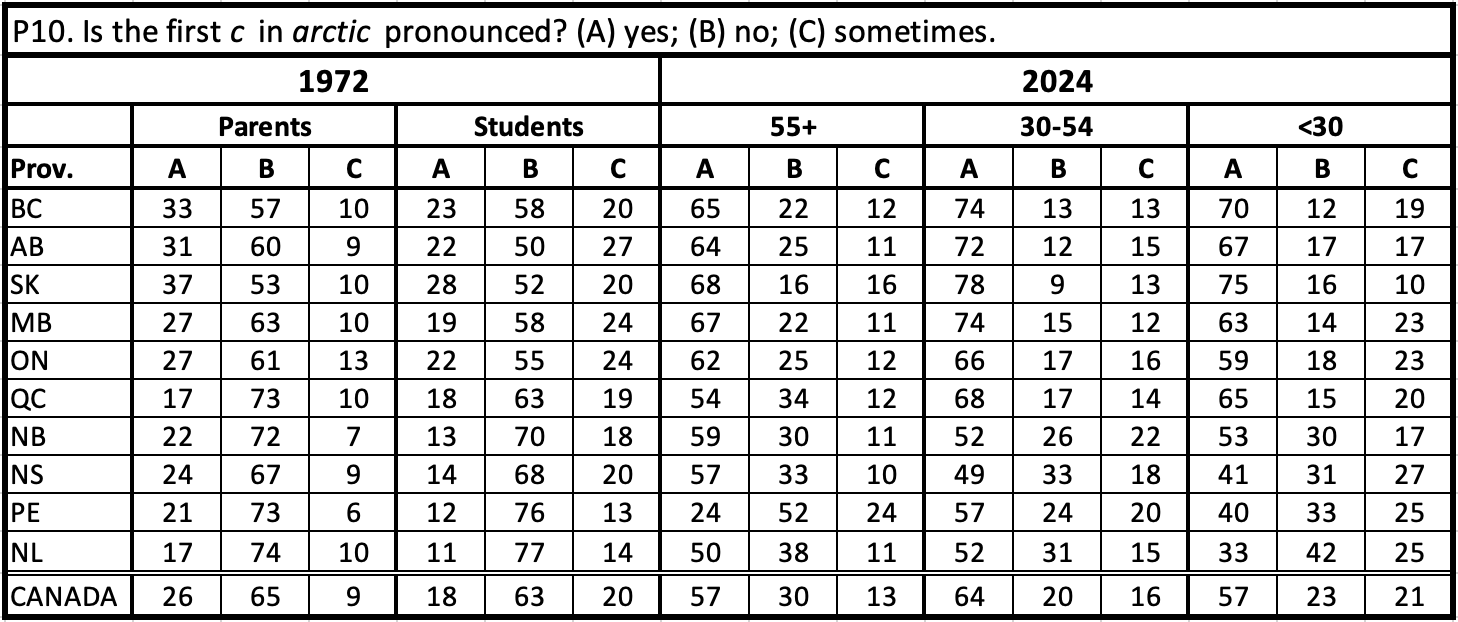

P10. Is the first c in arctic pronounced?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 56, Q42)

Arctic came into Middle English from Old French artique, without the c, but the French form was ultimately derived, via Latin, from Greek arktikos, which led to a corrected, classically-influenced spelling and corresponding pronunciation with the c in later English. Oxford gives only the c-pronunciation for British English, but Webster and Canadian dictionaries allow both in North America, with the c-less variant less frequent. In Canada, however, it was strongly preferred in 1972, by almost two thirds of respondents, especially those in the eastern half of the country (1972:56, Q42). This is no longer true: in 2024, the proportions are reversed, with the majority now preferring to pronounce the c, especially in Western Canada, while those who prefer to drop the c are now in the minority.

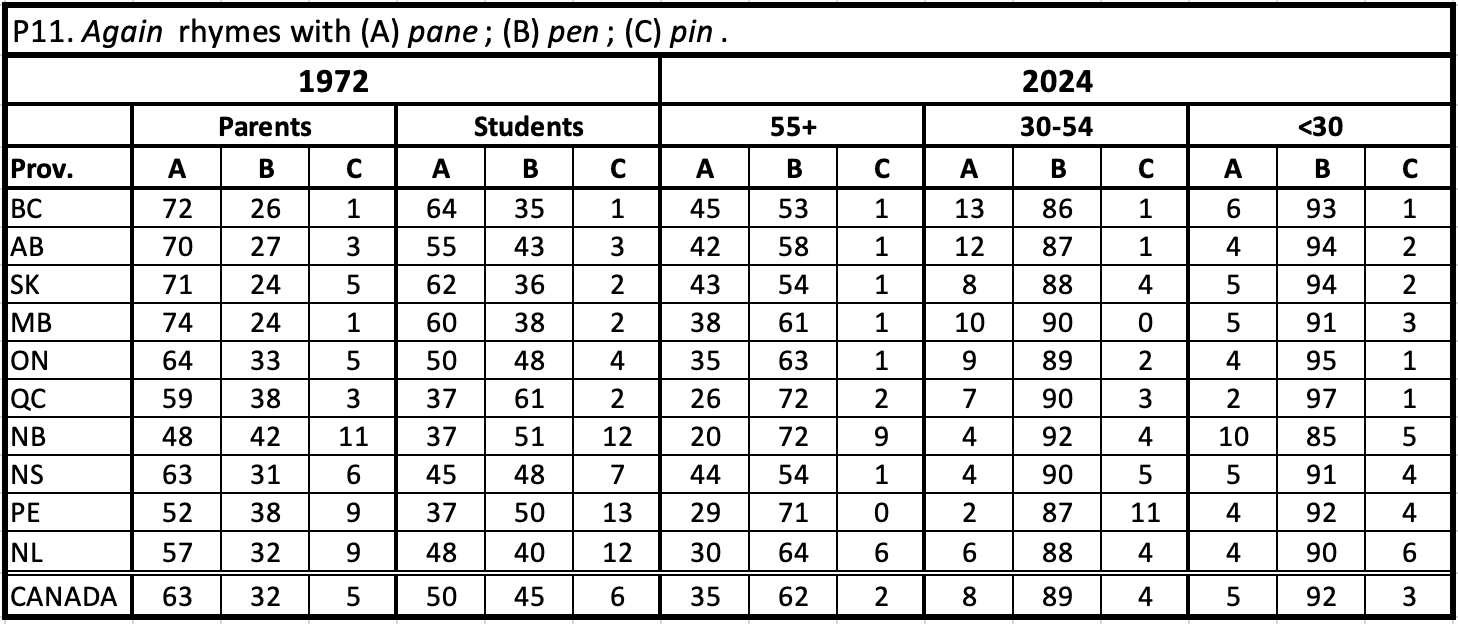

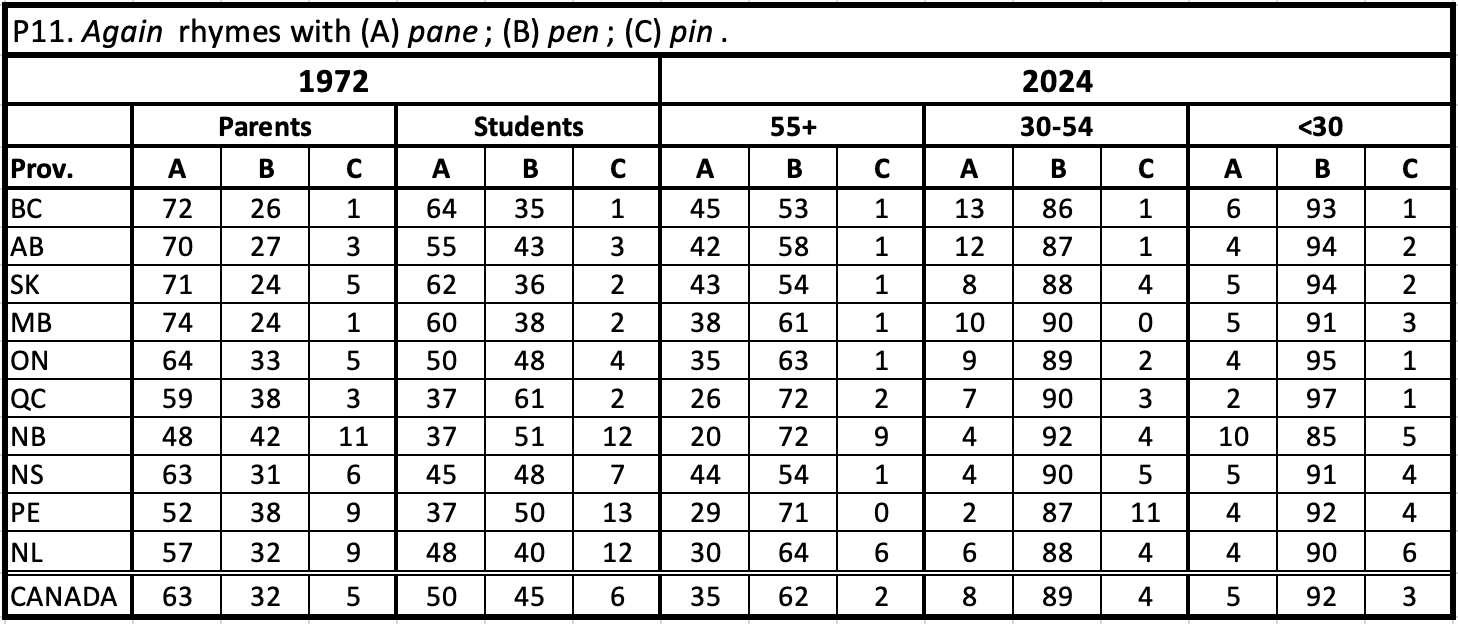

P11. Again rhymes with pane or pen.

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 60, Q59)

Dictionaries of British, American and Canadian English agree that both pronunciations of again are acceptable, but give that rhyming with pen first, suggesting that is the more frequent pronunciation. In Canada, however, the pronunciation rhyming with pane was once dominant, especially in Western Canada, with almost two thirds of parents preferring it in 1972, though this dropped to only half of the students (1972:60, Q59); Avis also cites the pane-pronunciation as a Canadian shibboleth (1956:45). In 2024, nevertheless, the shift of the 1972 students toward the more common pen-pronunciation is completed, rising from 62% of the oldest respondents to 92% of the youngest.

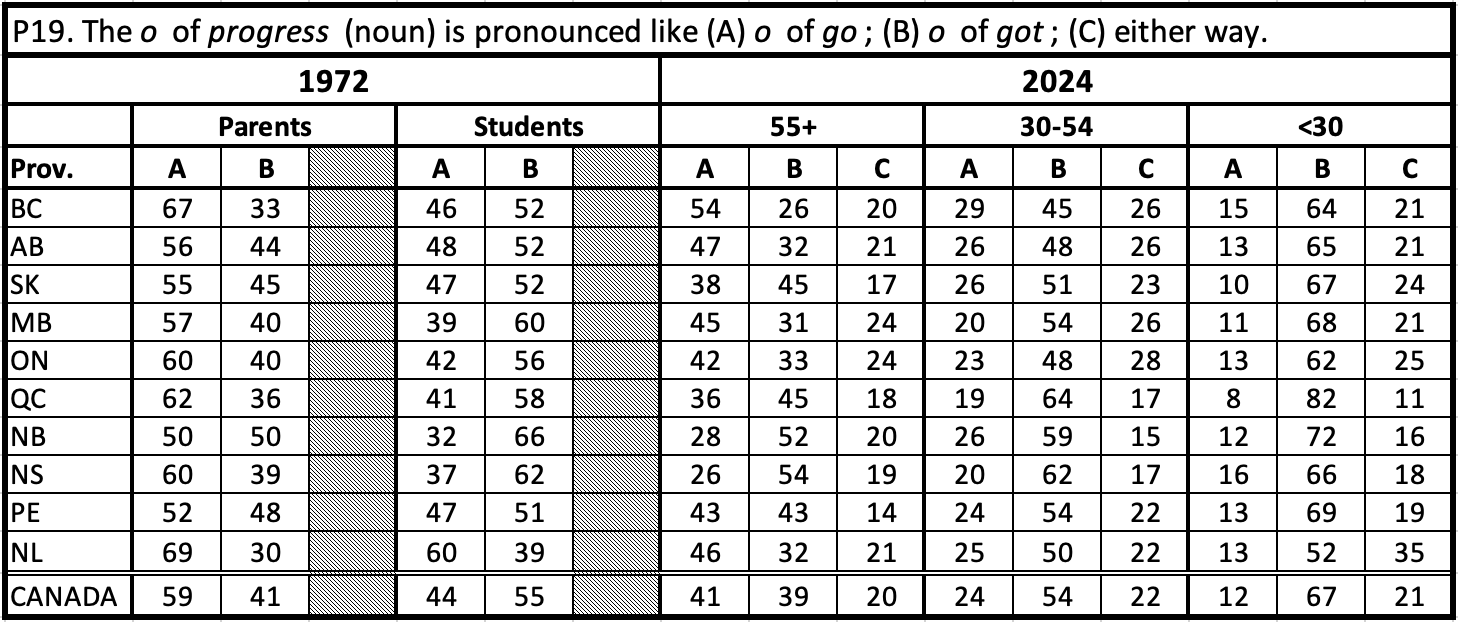

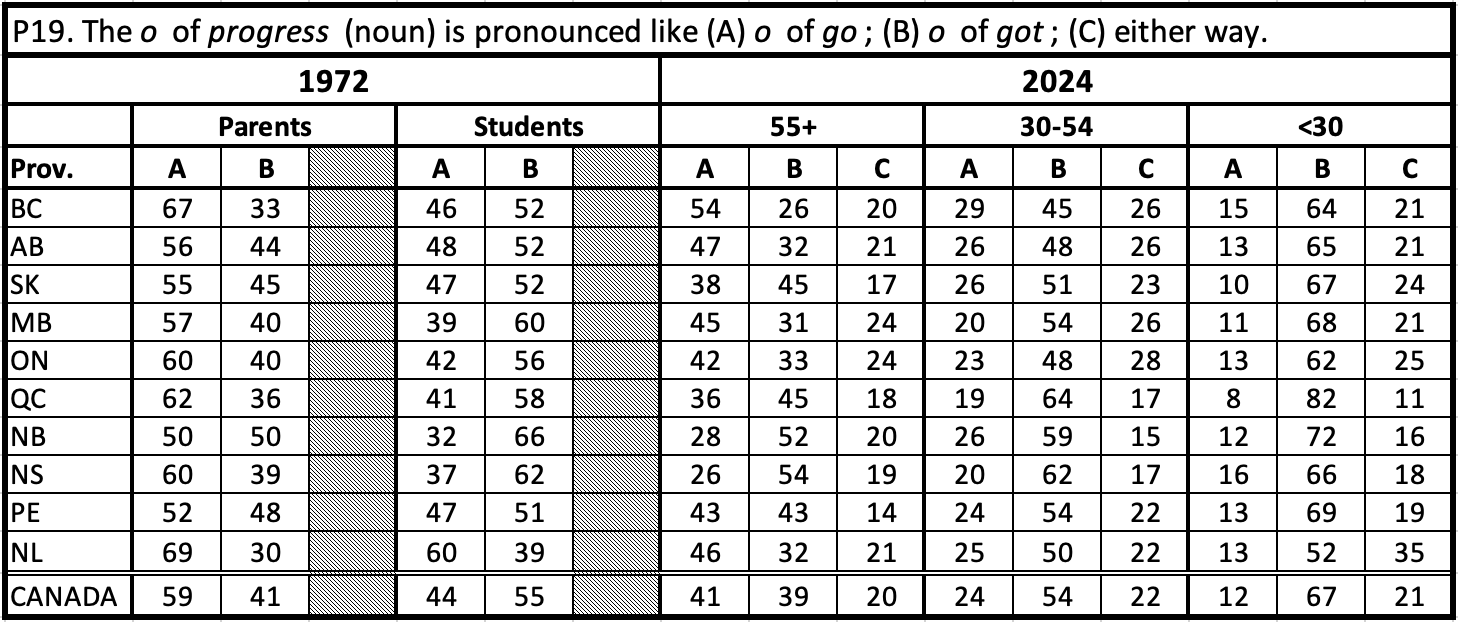

P19. The o of progress (noun) is pronounced like go or got.

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 67, Q91)

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 66%, B 34% (p. 45)

Oxford gives only the go variant, pro-gress; Webster gives this as a second (less common) variant in American English and associates it also with British English, giving the got variant, prog-ress, as the usual American pronunciation. Avis (1956: 45) records that two thirds of Ontarians preferred the British variant at mid-century, a proportion that began to diminish in the following decades: in 1972, the go variant was chosen by 59% of parents and 44% of students. The new data show the virtual completion of that trend, with the go variant declining further from 41% among the oldest group to only 12% among the youngest, who now prefer the American got variant by 67%, a reversal of the pattern of the 1950s.

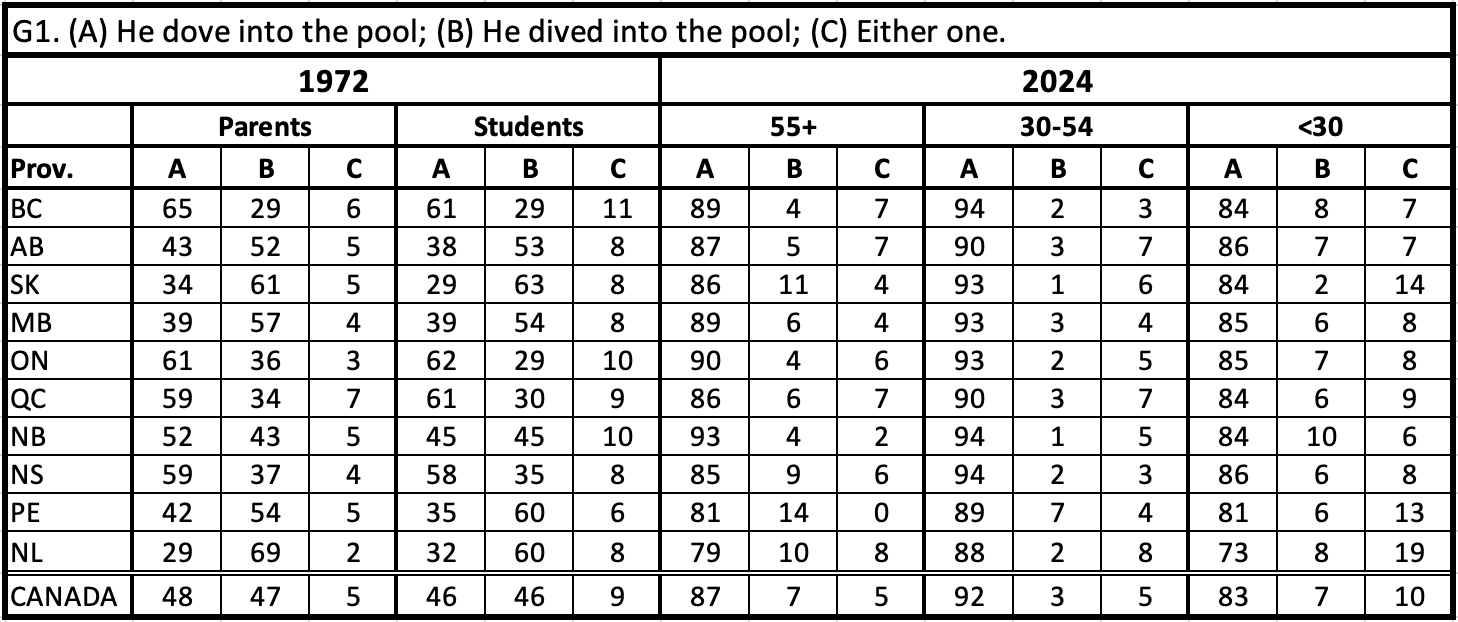

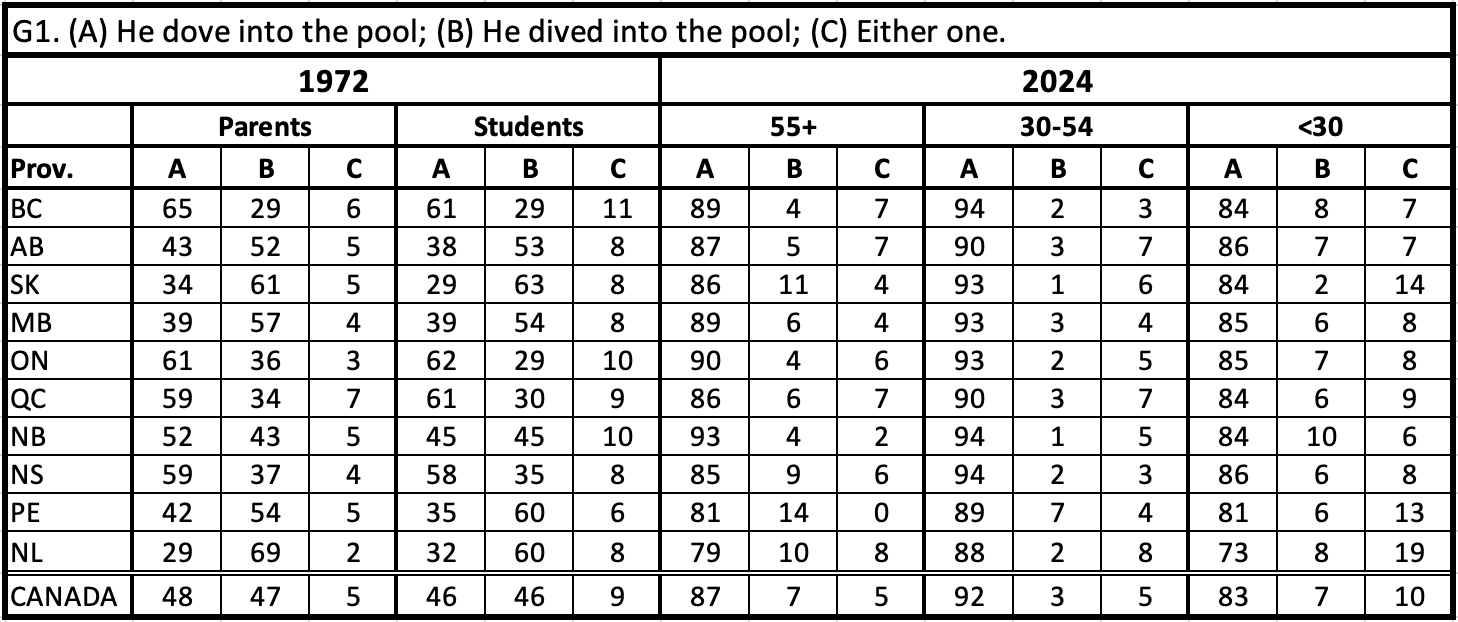

G1. He dove/dived into the pool.

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 72, Q23)

Dive was originally a ‘weak’ verb with a regular past tense form, dived, but later developed an alternative ‘strong’ past form, dove. Oxford labels dove an Americanism, but Webster gives both for American English and says the proportions vary regionally. Avis found that dove predominated in Ontario at mid-century (1955:14), a pattern also seen in 1972, when Ontario has the highest proportion of dove in the country, reaching 61-62%. Dove is less popular in other provinces, however, and the two forms garner equal support nationwide, around 47% each (1972:72, Q23). In 2024, by contrast, dove predominates strongly, with over 80% of all three generations preferring it; dived has all but disappeared, with less than 10% support. (See also Chambers 1998:19-22.)

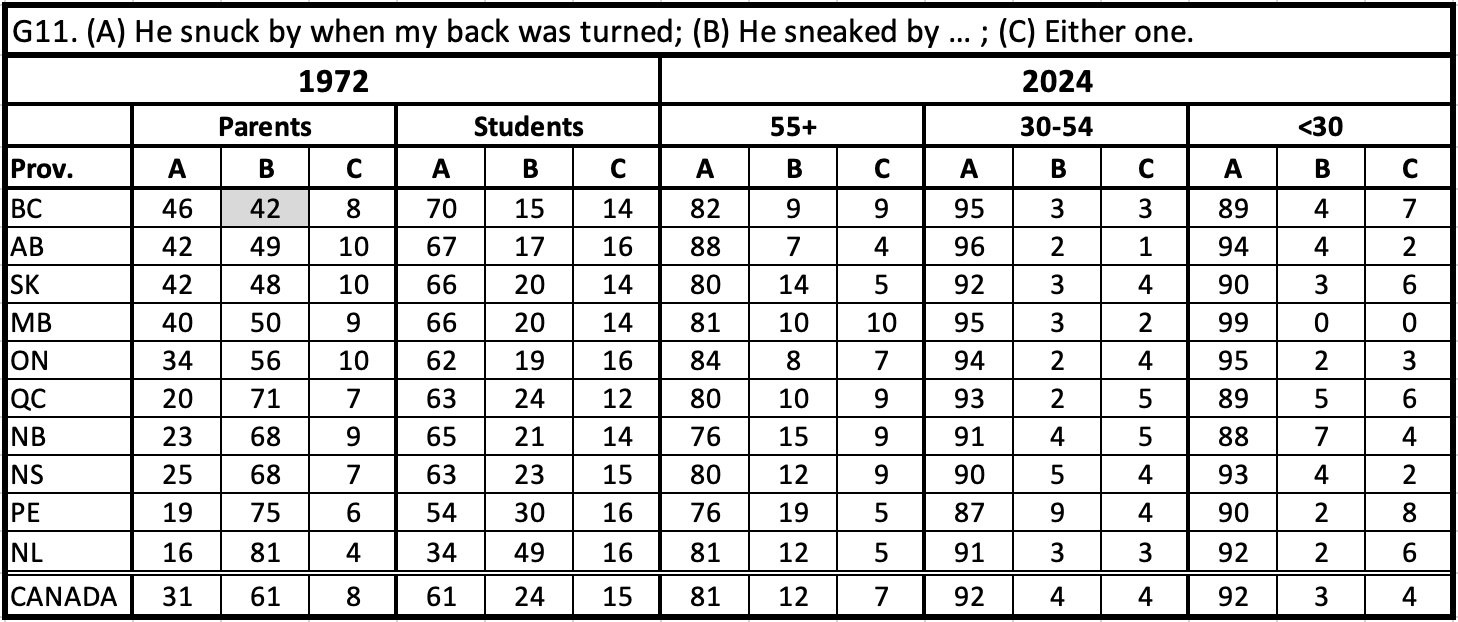

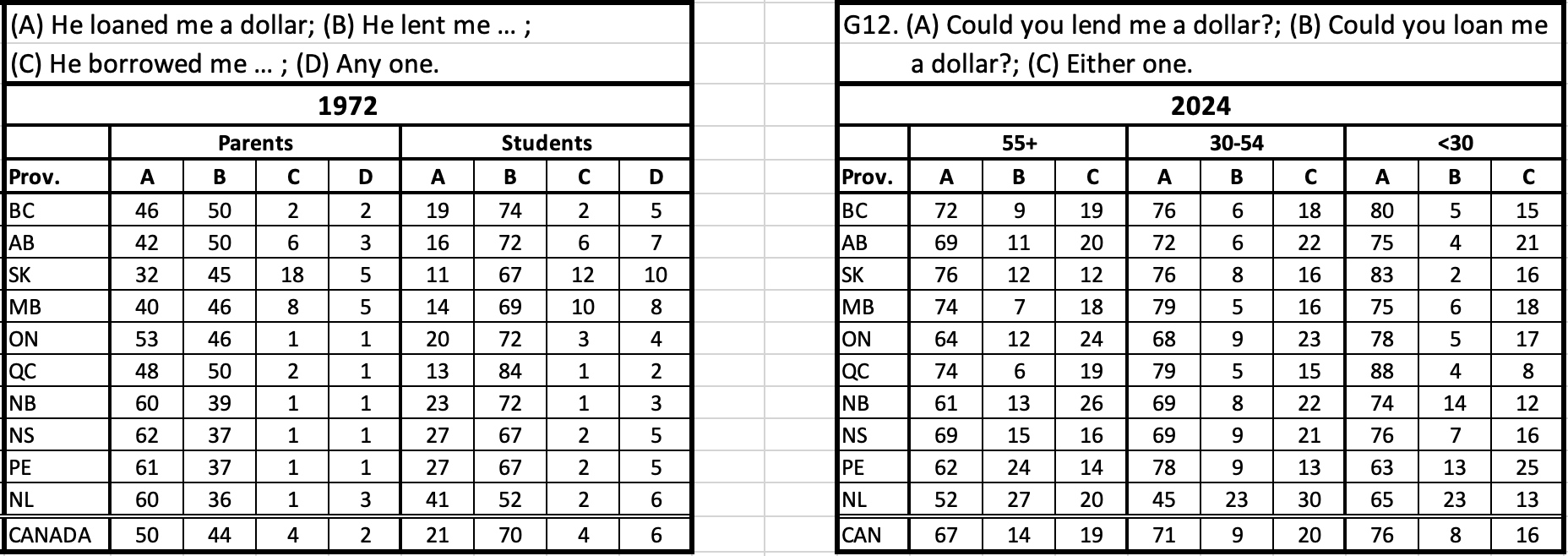

G11. He snuck/sneaked by when my back was turned.

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 83, Q89)

Note: The greyed out cell is an estimate

This variable showed a dramatic generational change in 1972, from two-thirds dominance of sneaked among parents to two-thirds dominance of snuck among students (1972:83, Q89). That shift is more or less completed in 2024, with preference for snuck rising over 80% among the oldest respondents and reaching 92% among the middle and youngest generations; following its dominance in the mid-20th century, sneaked has virtually disappeared from modern Canadian English. Webster gives both forms for American English but says snuck has come to dominate North American usage, as our data show, while in Britain, Oxford still labels snuck colloquial. (See also Chambers 1998:22-25, 2007:31.)

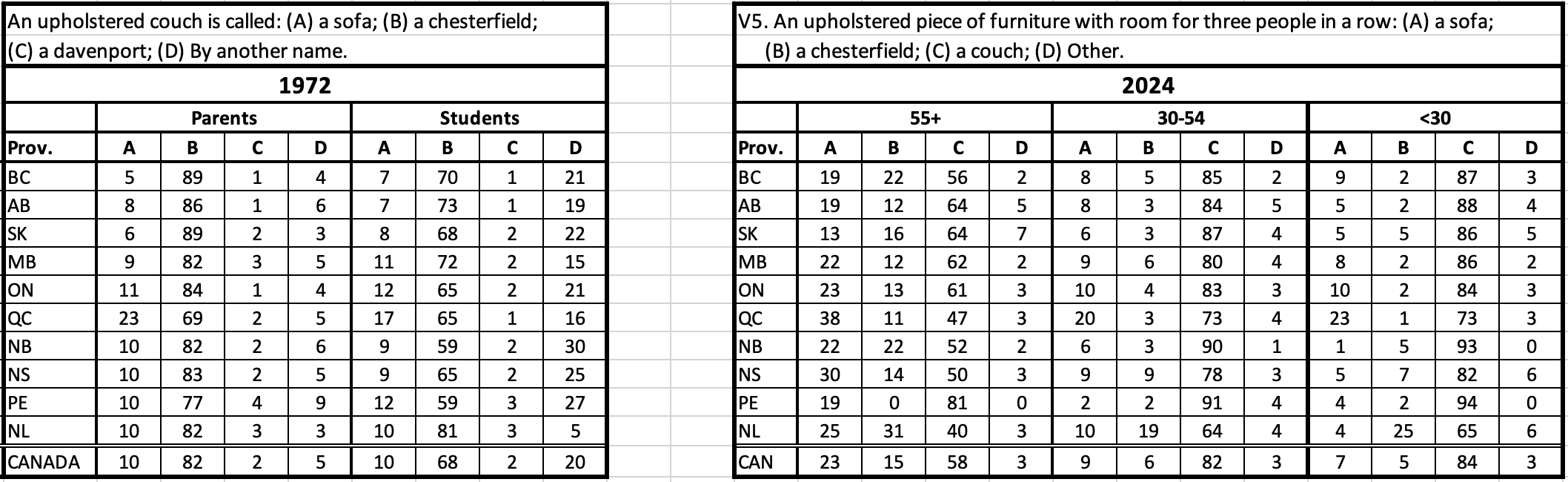

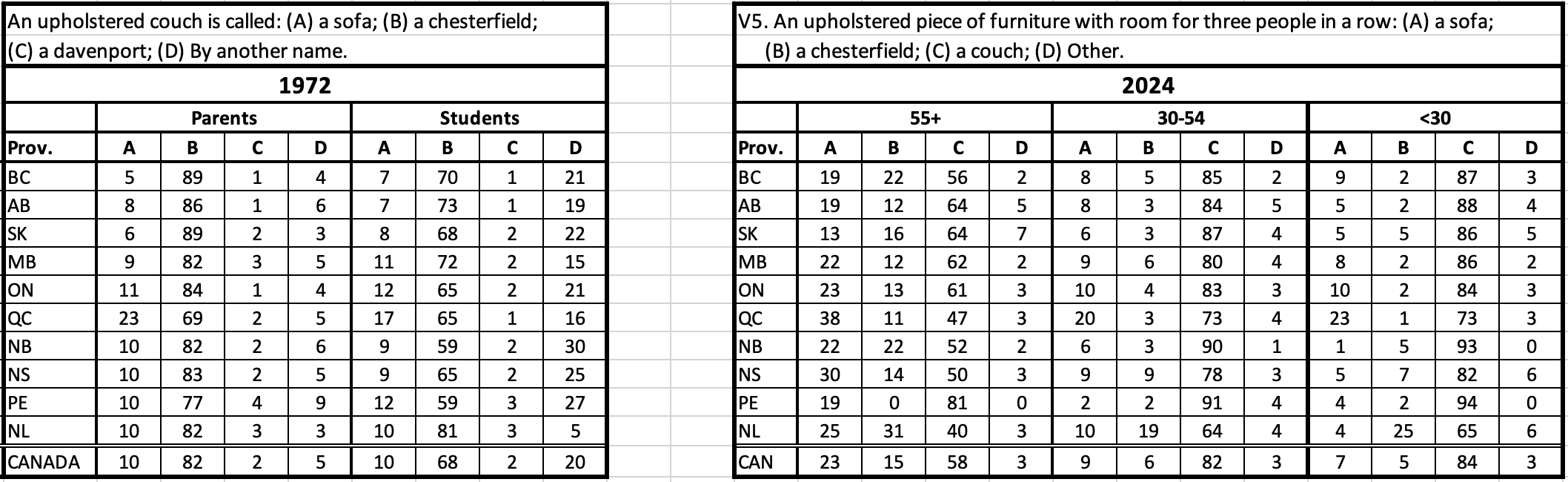

V5. Do you sit on a sofa, a chesterfield or a couch?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 86, Q29)

An upholstered piece of living room furniture that can accommodate three people in a row has many names across the English-speaking world: Oxford and Webster include entries for chesterfield, couch, davenport, divan, settee and sofa, sometimes specifying structural differences or alternative meanings (Webster’s first definition of chesterfield is a kind of coat; Oxford points out that a davenport is a kind of writing desk in Britain but a long seat in the U.S.). In Canada, the principal name used to be chesterfield: Avis labels this the normal Ontario term and reports its use by about 80% of his respondents, though the only alternative he lists is the “American” sofa, preferred by less than 10%; couch is absent from his analysis (1954:18). This problem reappears in 1972: chesterfield is shown to be the normal term not just in Ontario but across Canada, in every province, with an average of 82% of the parents choosing it, compared to 10% choosing sofa and 5% “another name”, which might have been couch (1972:86, Q29). A shift is already underway in 1972, however: preference for chesterfield slips to only 68% among students. In the 1990s, Chambers (1998:8-11) charted a sharp rise of the main American term, couch, at the expense of Canadian chesterfield. The new data confirm that trend: even among the oldest respondents, chesterfield has dropped to a mere 15%, with 58% preferring couch; among the youngest respondents, chesterfield has virtually disappeared (5%), with 84% now choosing couch.

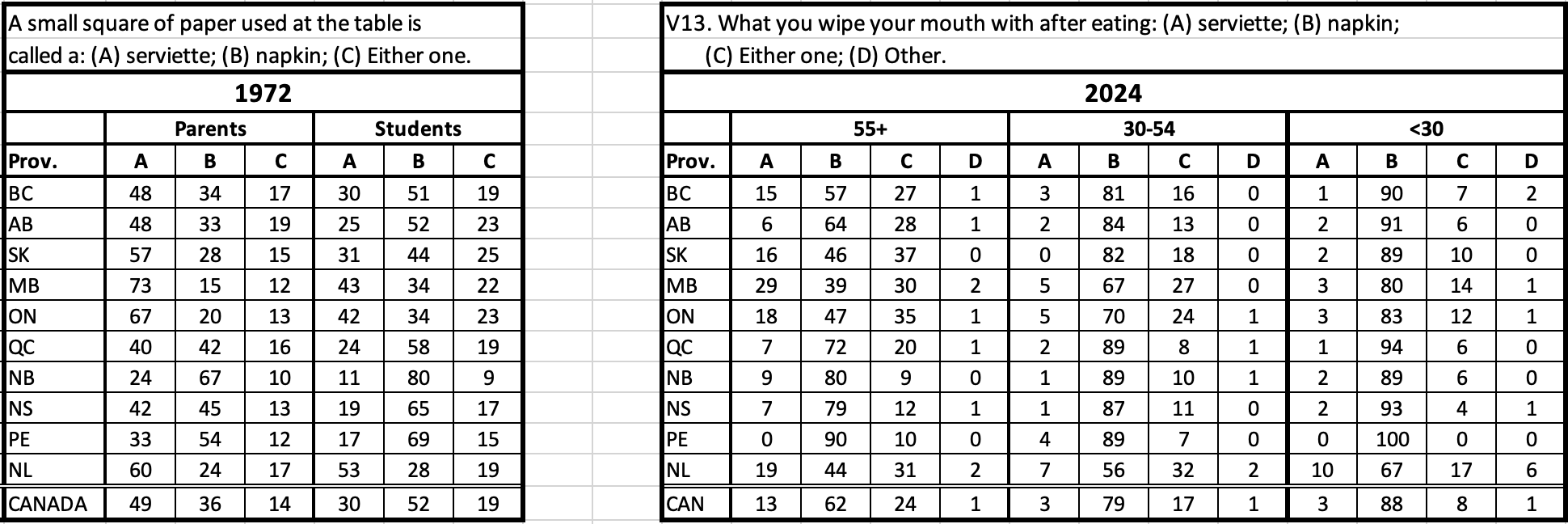

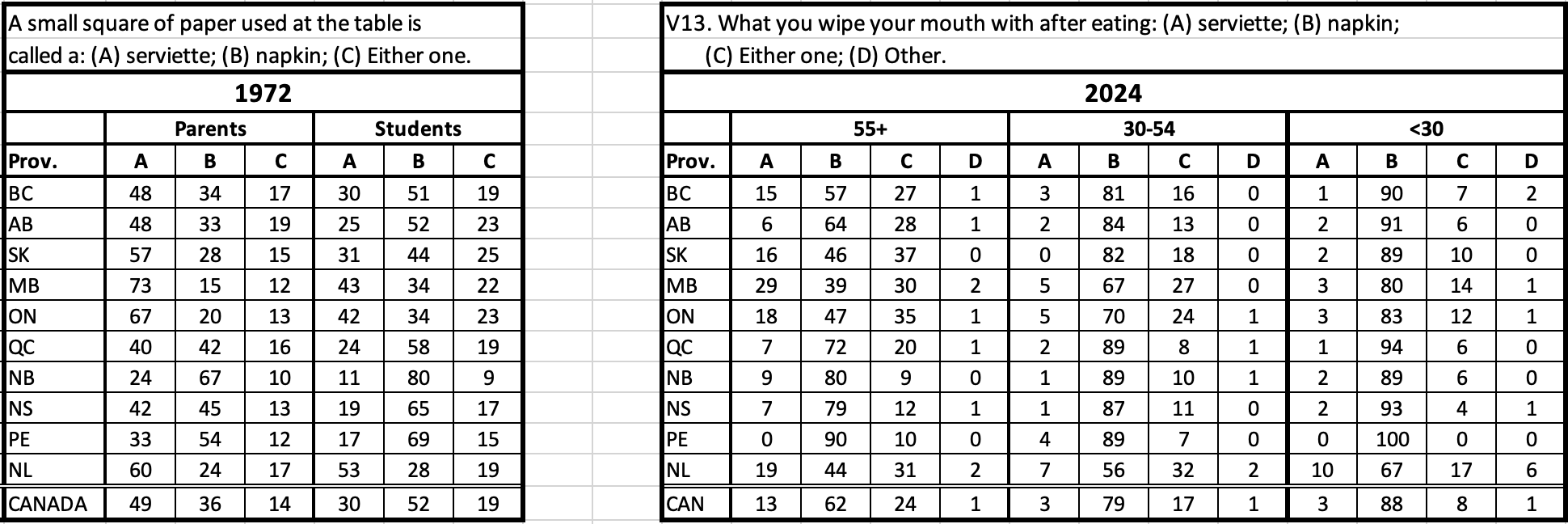

V13. Do you wipe your mouth with a serviette or napkin?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 90, Q58)

Oxford and Webster agree that the use of serviette for a table napkin is chiefly British. Avis associates it with Ontario English, where a majority of around 70% preferred it to napkin at mid-century (1954:18). By 1972, preference for serviette had dropped to half of parents and only 30% of students, with napkin growing correspondingly from 36% to 52% (1972:90, Q58). In 2024 we see this trend continue, with napkin increasing from 62% among the older respondents to 88% among the youngest; serviette has all but disappeared among young Canadians today, accounting for only 8% of their responses. (See also Chambers 1998:14-17.)

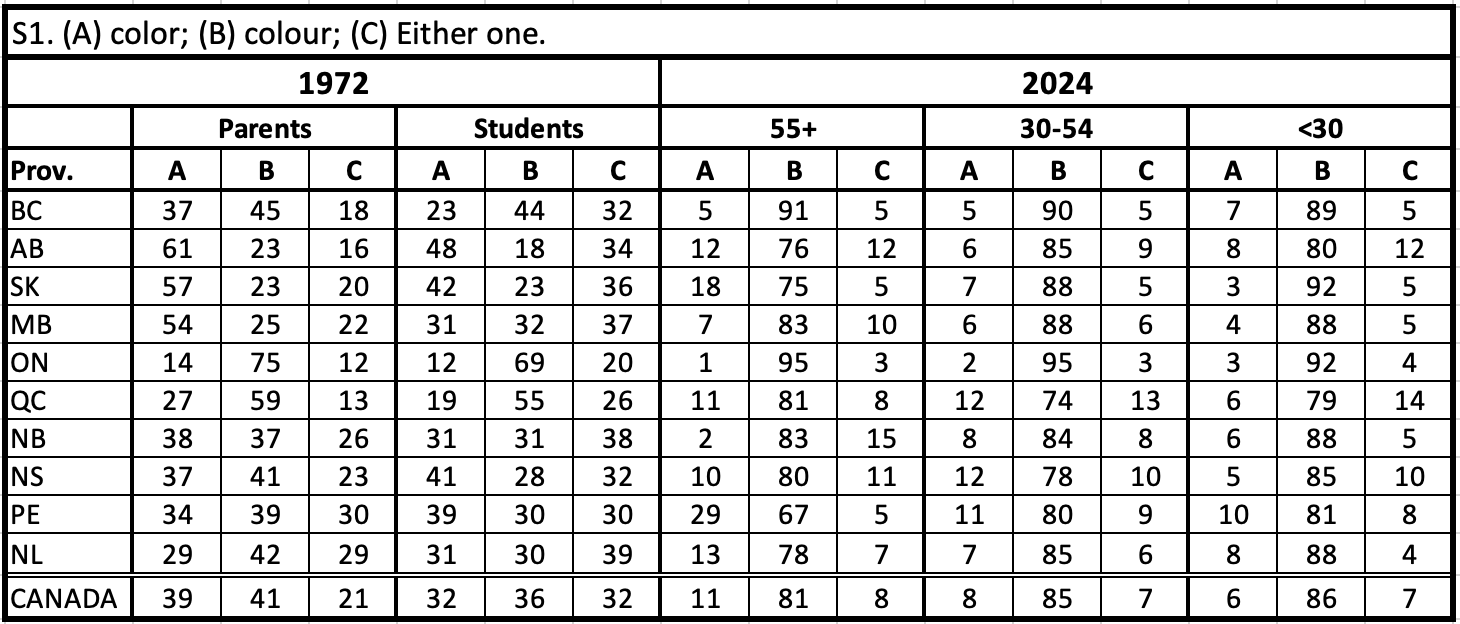

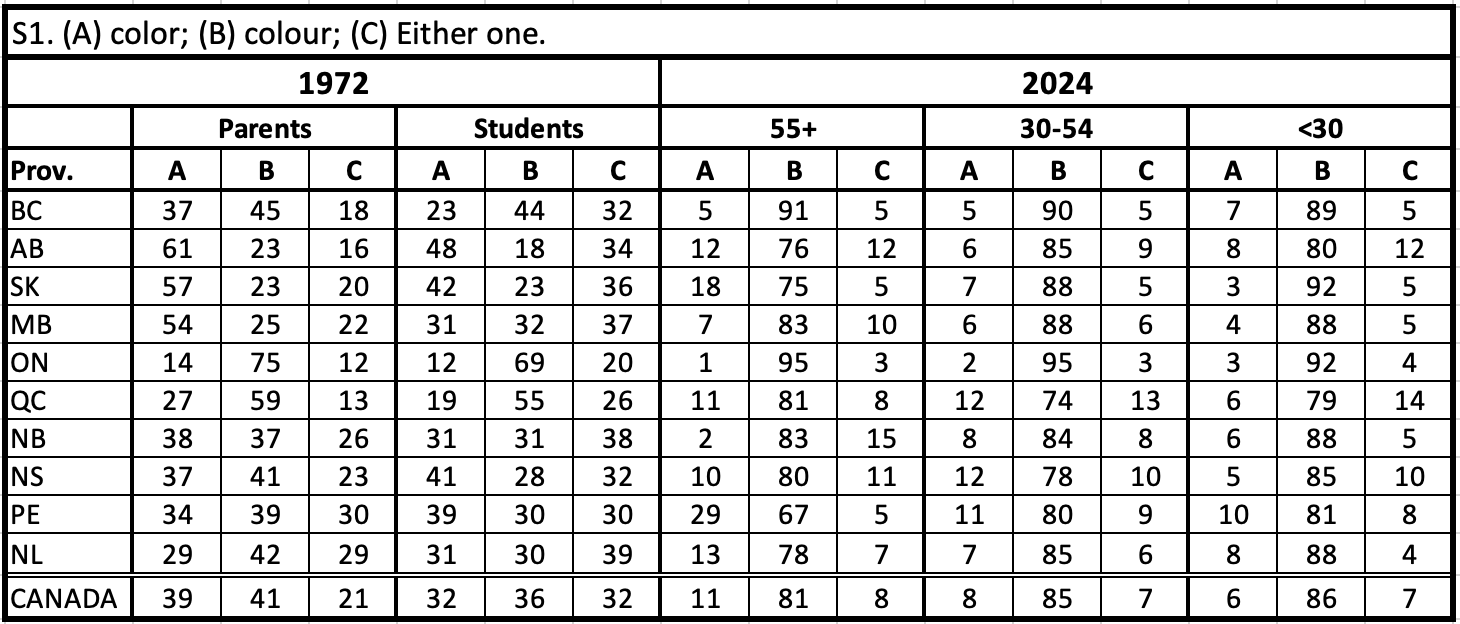

S1. Color or colour?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 101, Q10)

In 1972, respondents were more or less evenly split between the American (color) and British (colour) spellings, though there was a 50% increase in the “either one” option among the students (1972:101, Q 10). By 2024, colour, with the u, had asserted itself as the choice of a large majority of all three generations (over 80%), with less than 10% selecting color or “either one”. This presumably reflects the adoption of at least some British spellings as the standard in Canadian schools in the late 20th century.

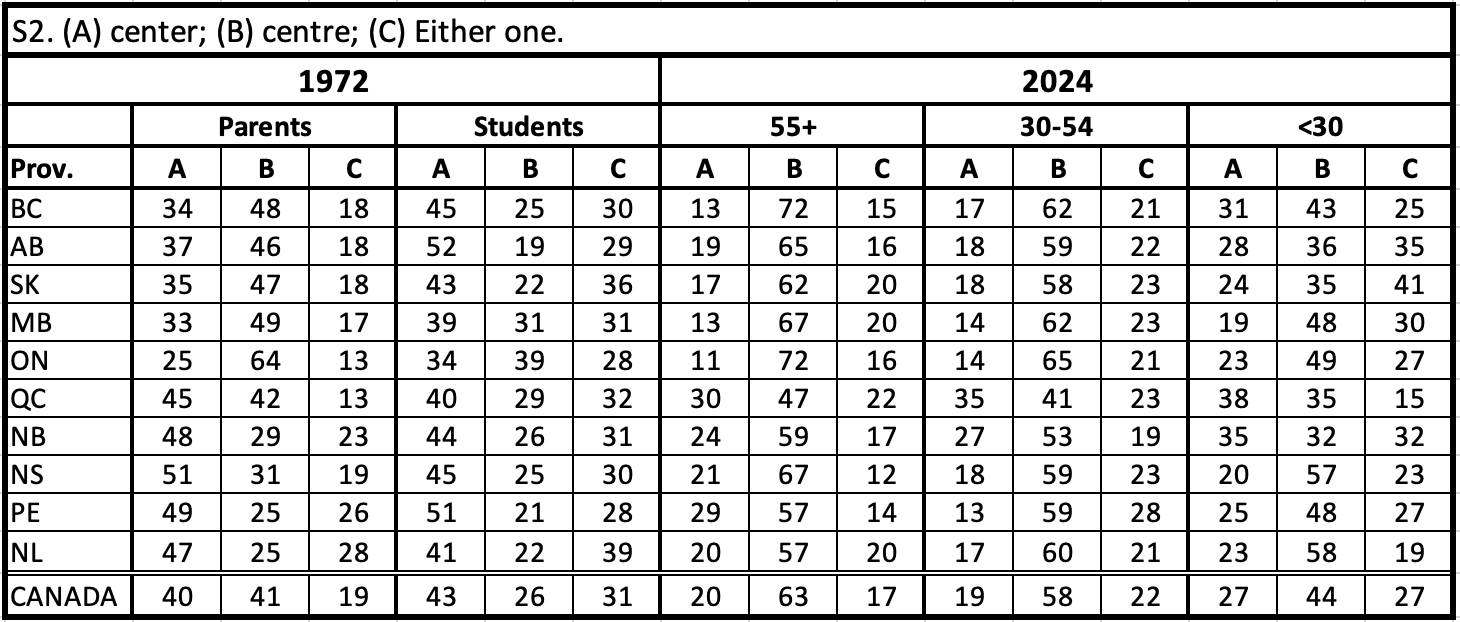

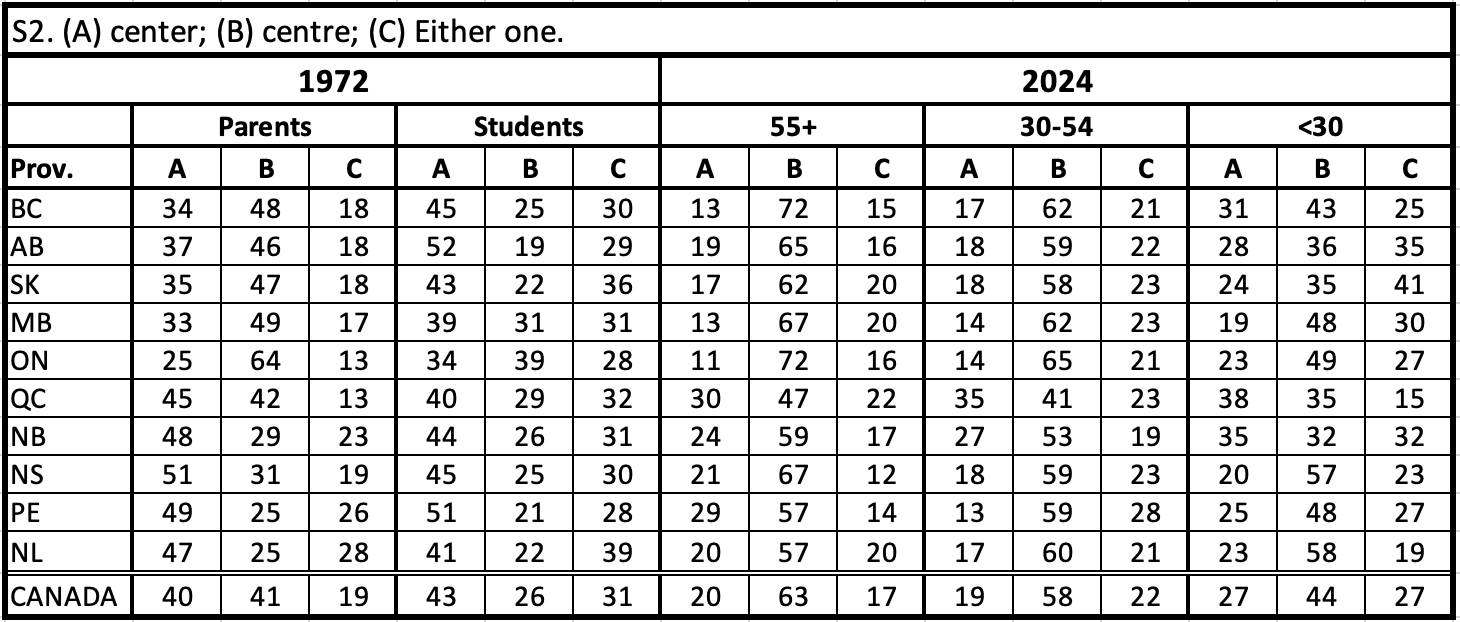

S2. Center or centre?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 101, Q11)

In 1972, parents were more or less evenly split between the American (center) and British (centre) spellings, but among the students there was a substantial shift away from preferring centre to accepting either spelling, while use of center remained stable (1972:101, Q 11). As with color and colour, however, use of the British spelling increases in the 2024 data, but not as sharply and it is now declining: it is preferred by 63% of the oldest respondents but only 44% of the youngest, with the remainder split between center and “either one”. In all three generations, use of the American spelling is highest in Quebec, despite (or perhaps because of?) the identity of the British spelling with the French spelling.

Regional variation today

Though the main focus of the New Survey of Canadian English is on a partial replication of and comparison with the original survey of 1972, another important focus is on variation and change in Canadian English today, as reflected in differences between provinces and age groups in the new data. A large set of new vocabulary questions not included in the original survey were added for precisely that purpose; in fact, these tend to involve considerably more inter-provincial variation than the 1972 variables. Following are the ten questions that display the most regional variation. The patterns they exhibit are similar to those identified in previous research, particularly in Boberg (2005, 2010, 2016), but the new dataset confirms these patterns with a much larger sample, as well as adding a few new variables.

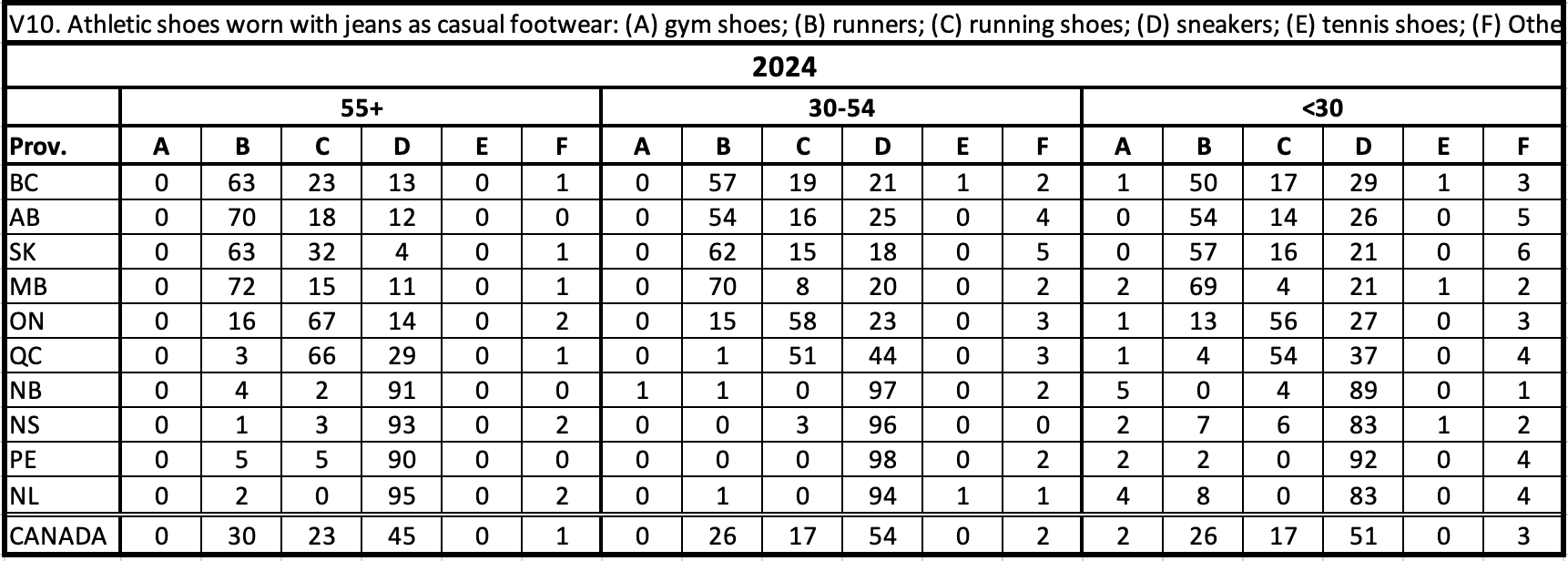

Reflecting their athletic origins, these shoes are called running shoes by most respondents in Ontario and Quebec (see also Chambers 2000:187-189) and runners by most in Western Canada, two terms that are more or less unique to Canada. In Atlantic Canada they are called sneakers, which is also the most common American term. The other American terms, gym shoes and tennis shoes, and the usual British word, trainers, are virtually nonexistent in Canada.

V11. A small house in the countryside where people go on summer weekends.

Note: Nova Scotia "other" is mostly bungalow

The set of words for this building shows clear regional differences across the country. In Western Canada this is a cabin, though older respondents in Manitoba prefer the Ontario word, cottage. Cottage also dominates the Maritimes, but has some competition in Quebec from the French word chalet, which means a ski lodge outside Quebec; moreover in Montreal, cottage can refer to a two-story house in the city, as opposed to a bungalow. Bungalow is the local term on Cape Breton Island, while some people in New Brunswick, as well as Northwestern Ontario, use camp, which would elsewhere be a place to pitch a tent, not a structure. Finally, in Newfoundland, western cabin reasserts itself.

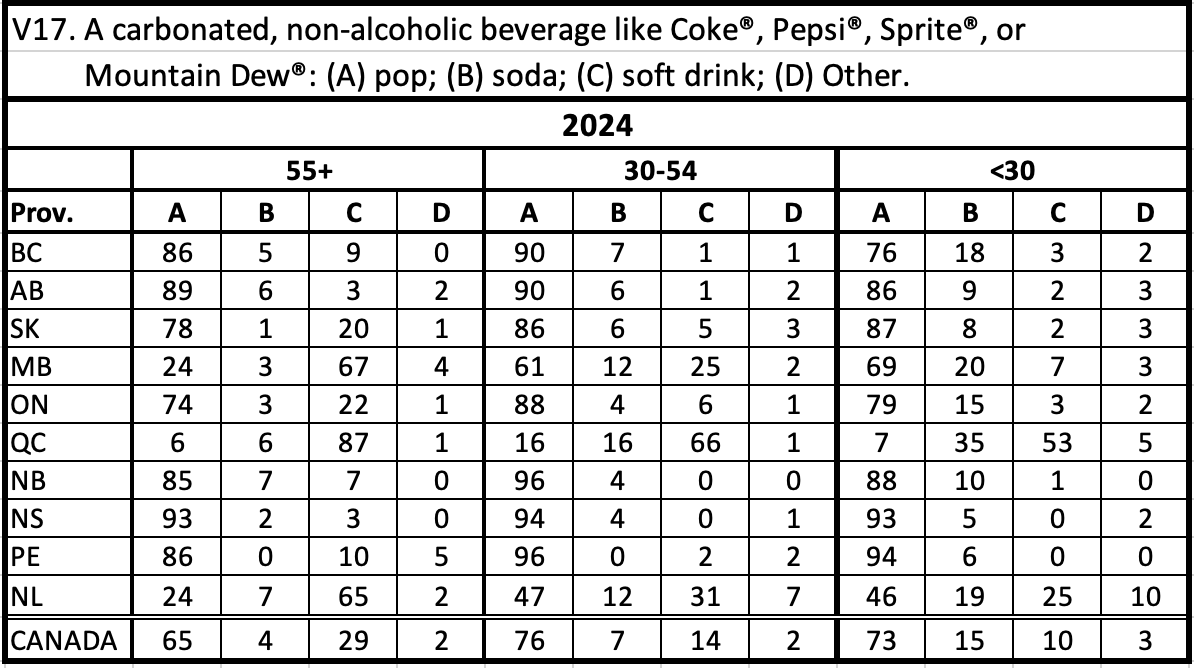

This is one of the best-known regional vocabulary variables across North America, on which Americans are famously divided. Collectively, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Sprite, Mountain Dew and other brands are called soda on the northeast and southwest coasts (e.g. in New York City and Los Angeles) and in parts of the Midwest (particularly Wisconsin and Missouri); pop in the remainder of the Midwest and Northwest; and coke, used generically, in most of the South. Still other terms occur in smaller regions, like tonic in eastern New England, at least traditionally, and cold drink in parts of the South. Along most of the northern border, however, it is pop that dominates American usage, which perhaps explains its preponderance across that border in Canada, where it rises from two thirds of the oldest respondents to three quarters of the middle and youngest groups, reaching a peak of 90% or greater among middle-aged respondents in British Columbia, Alberta and the Maritimes. As in the U.S., however, there are important regional exceptions, most notably Quebec, where pop is chosen by less than 10% of the oldest and youngest groups, though there is a bump up to 16% among the middle group. As also found in previous research by Chambers (2000: 190-193), the dominant Quebec term is soft drink, accounting for 87% of older responses, though it declines to 66% for the middle group and only 53% for the youngest. Challenging it now is the most popular American term, soda, preferred by a third of younger Quebec respondents. Soft drink is also the dominant term among older Manitobans (67%) and Newfoundlanders (65%), but it is now declining in those provinces, as well, giving way not to soda, as in Quebec, but to pop, the dominant term in neighboring regions of Canada.

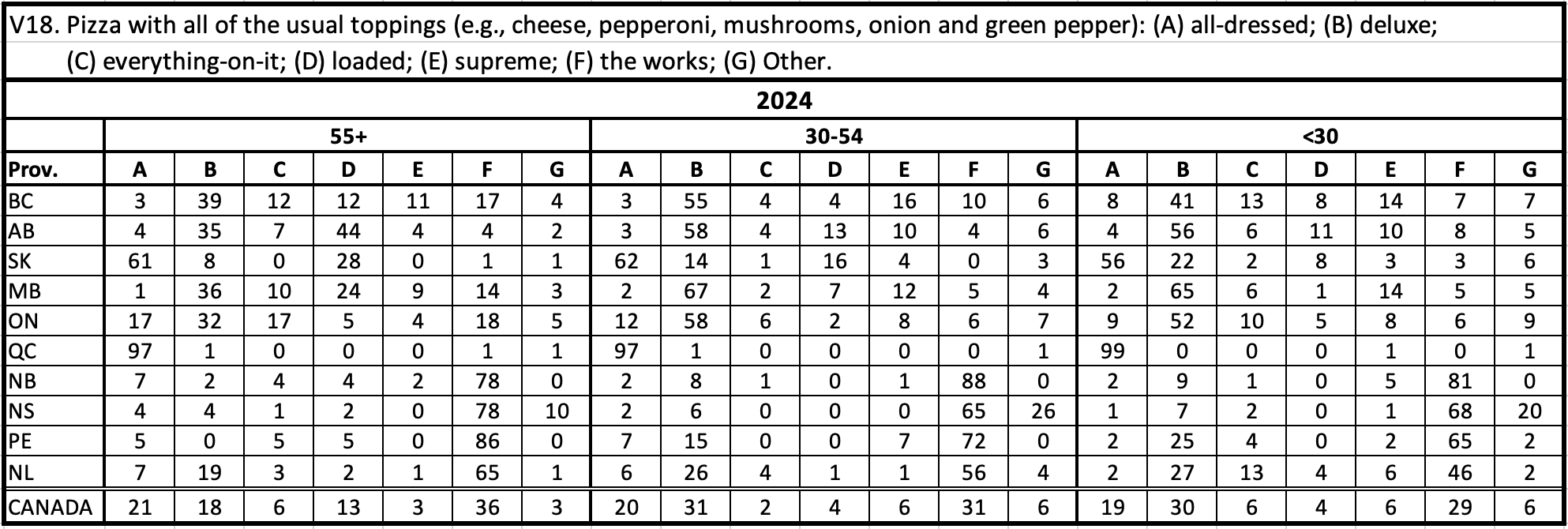

Since Italian immigrants introduced pizza to Canada after the Second World War, it has become one of Canada’s most popular meals, perhaps because of the wide variety of toppings available to suit different tastes. Pizzerias have developed different words for the topping combinations they offer, including the standard or most common set, which usually includes cheese, pepperoni, mushrooms, onion and green pepper. In Quebec, this combination is known as all-dressed, a term also used there for hamburgers and hotdogs, with a close French equivalent, toute-garnie. Use of all-dressed reaches almost 100% of all three generations in Quebec, but is curiously also chosen by around 60% of respondents in far-away Saskatchewan. In the rest of Western Canada and Ontario, deluxe is the most popular word, though loaded is also strong, especially in Alberta (44%), while the works dominates Atlantic Canada, especially the Maritimes.

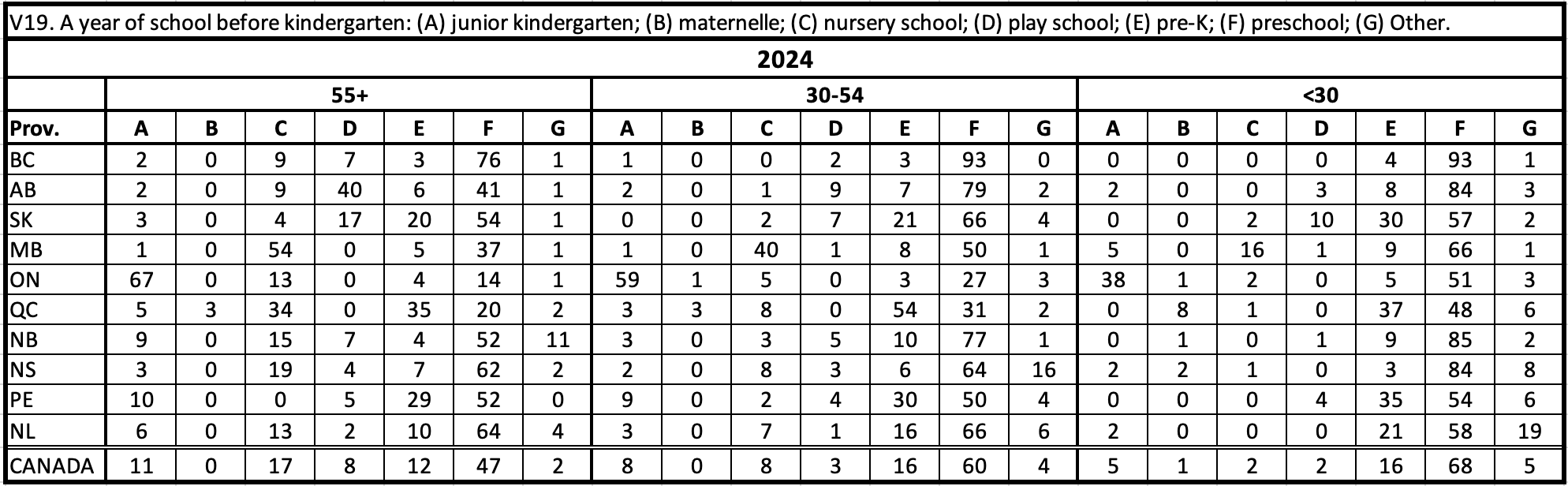

There are several words for the year of school before kindergarten, which may be partly determined by the official usage of provincial education departments rather than by individual choice. The most common term across Canada is preschool, which increases from under half of the older respondents to over two thirds of the youngest. The most important regional exception to this is junior kindergarten, which is more or less unique to Ontario, but loses ground to preschool among younger respondents (and may suffer from disagreement or confusion about what precisely it refers to). Older respondents in Alberta chose playschool at an equal rate to preschool, but this also gives way to the national term among the younger set. Elsewhere, the main contender is pre-K, which is strongest in Saskatchewan, Quebec and Prince Edward Island, an unusual and non-contiguous set of locations; only among middle-aged and older respondents in Quebec, however, does it surpass preschool. Many Newfoundland respondents offered KinderStart, the name of a provincial government school transition program in that province; similarly, some Nova Scotians call it pre-primary, a term used by their provincial government’s Department of Education.

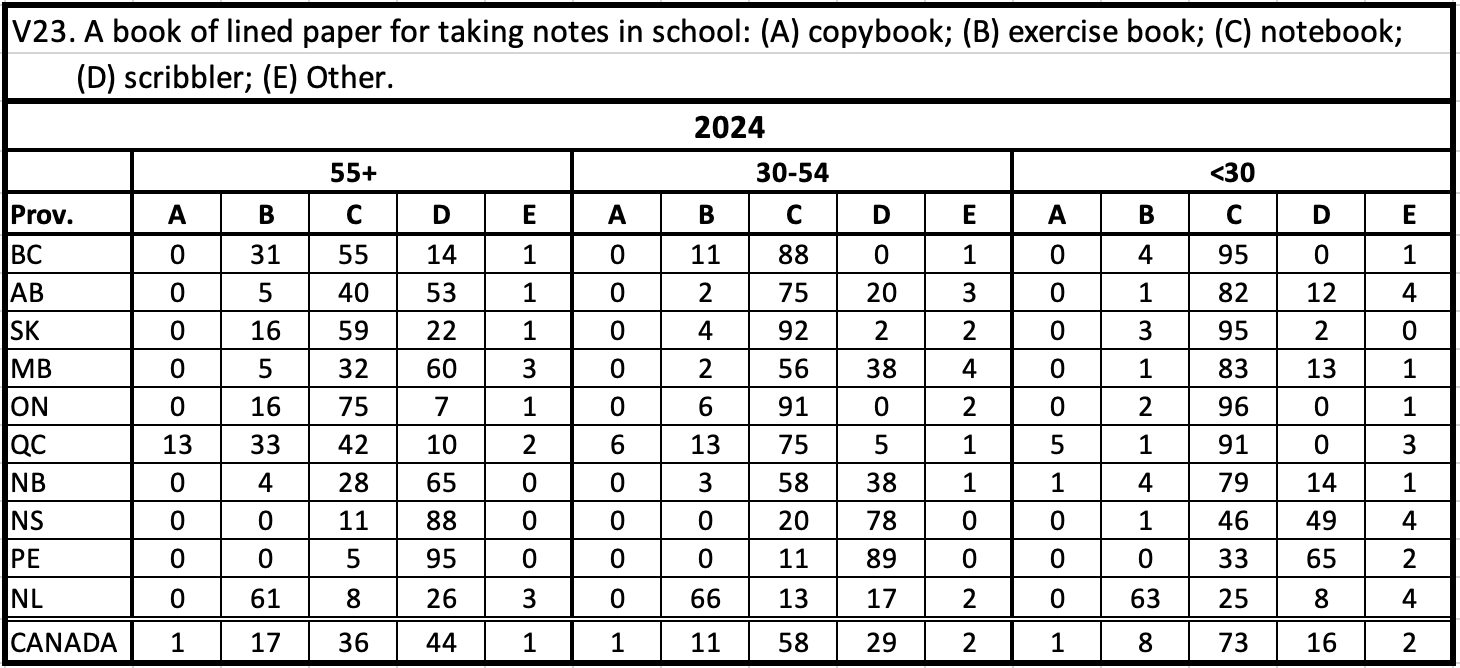

The usual American word for this is notebook, which is also the dominant choice across much of Canada today, but in several places a unique Canadian word, scribbler, competes with it: among older respondents this is in fact the dominant term in Alberta, Manitoba and all three Maritime provinces, with a peak at 95% on Prince Edward Island. This makes for a 44% showing in Canada overall in that age group, compared to only 36% for notebook. Among later generations, however, use of scribbler declines sharply, to 29% and then 16%, while notebook grows, from 58% to 73%; among the youngest respondents, scribbler retains its dominance only on Prince Edward Island, while in Nova Scotia it remains slightly ahead of notebook. In Newfoundland, the usual British term, exercise book, is chosen by around two thirds of all three generations, as well as by around a third of older respondents in British Columbia and Quebec.

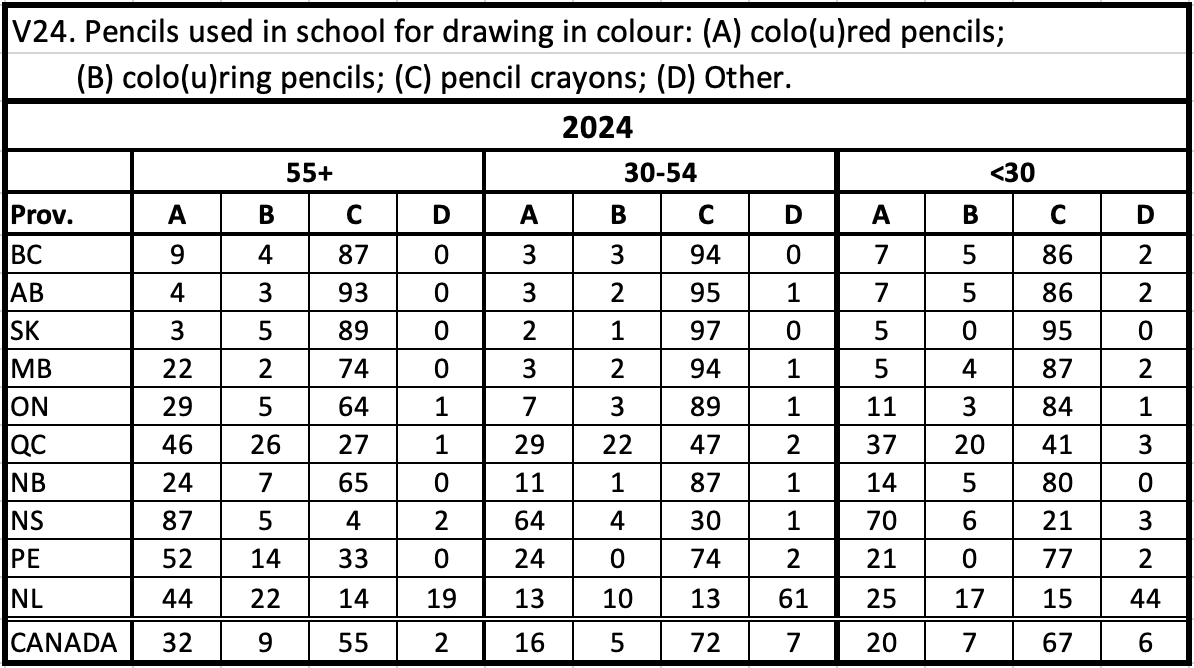

This staple of school supplies lists, like notebooks or scribblers, has a unique Canadian descriptor: pencil crayons, indicating a fusion of the graphite tip of a pencil with the colors of a pack of crayons. That is the dominant term across Canada, but is particularly strong in Western Canada and Ontario, as well as New Brunswick and among younger respondents on Prince Edward Island. The American term, colored pencils, is the dominant choice in Nova Scotia and among older respondents in Quebec, while many people in Newfoundland call them coloring or colored leads.

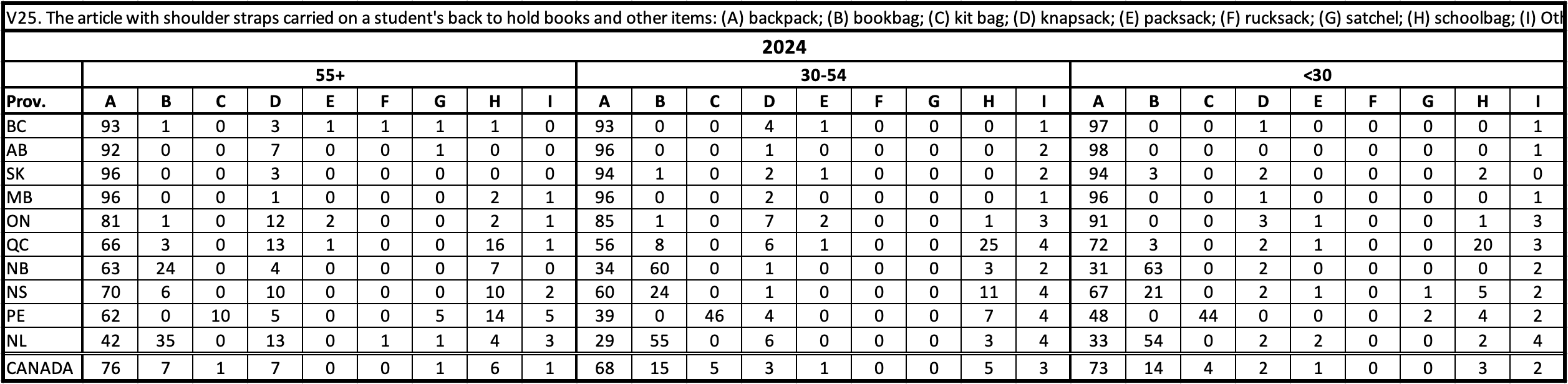

The usual term across North America for this item is backpack, which accounts for around three quarters of Canadian usage. The second-most popular term is bookbag, an Atlantic Canadian word that is the dominant choice among middle-aged and younger respondents in New Brunswick and Newfoundland and is in second place for the same groups in Nova Scotia. Prince Edward Island in this case goes its own way with kitbag, a term that has military rather than scholastic connotations elsewhere but competes for dominance with backpack among middle-aged and younger islanders. Finally, schoolbag is the second choice after backpack for all three generations in Quebec.

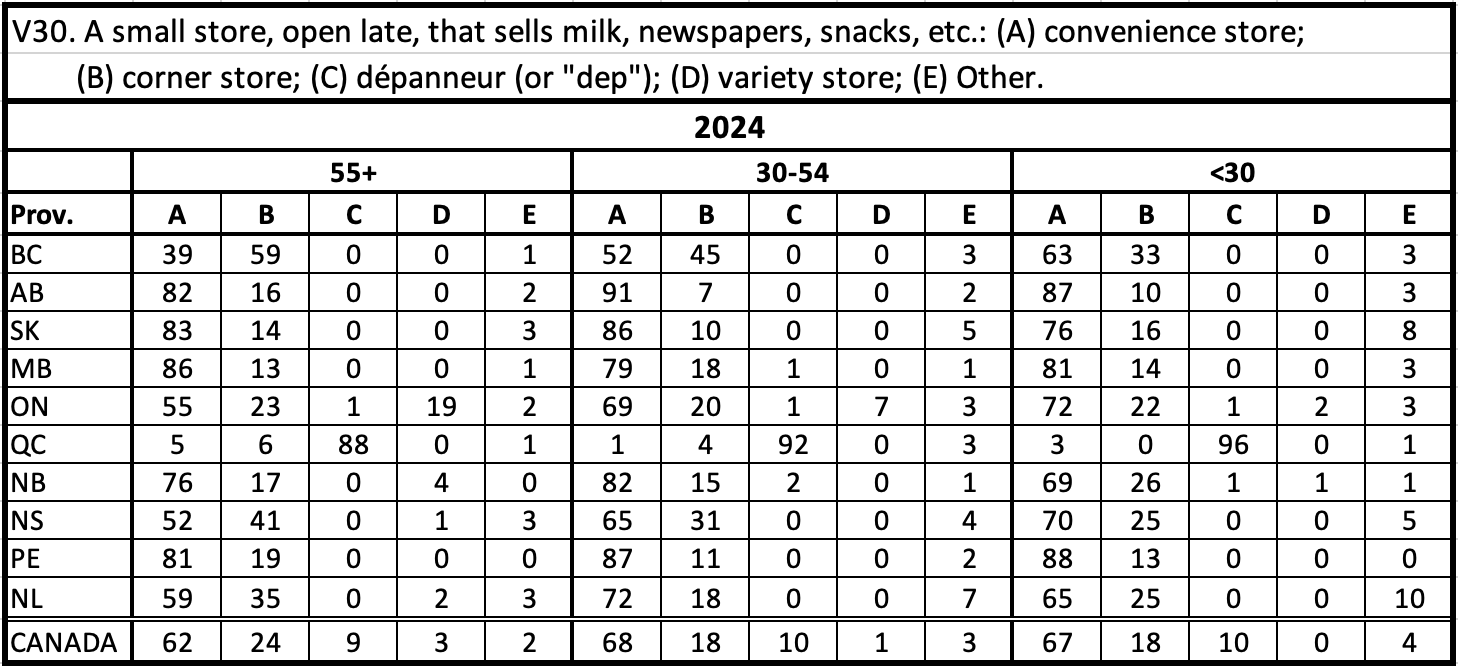

The main interest of this set of words is the term used exclusively by the vast majority of Quebec’s English-speaking population, which is a classic example of a Gallicism, or borrowing from French: dépanneur, often shortened by Anglophones to dep. In France, this means a repair shop (panne is a breakdown, so dépanner means ‘to repair’), but across Quebec, in French and English, it denotes what elsewhere in Canada are mostly called convenience stores. Another popular term outside Quebec is corner store, which dominates among older respondents in British Columbia and is also a strong contender among older and middle-aged respondents in Nova Scotia. A fourth term, variety store, is found only as the third-ranked term among older Ontarians.

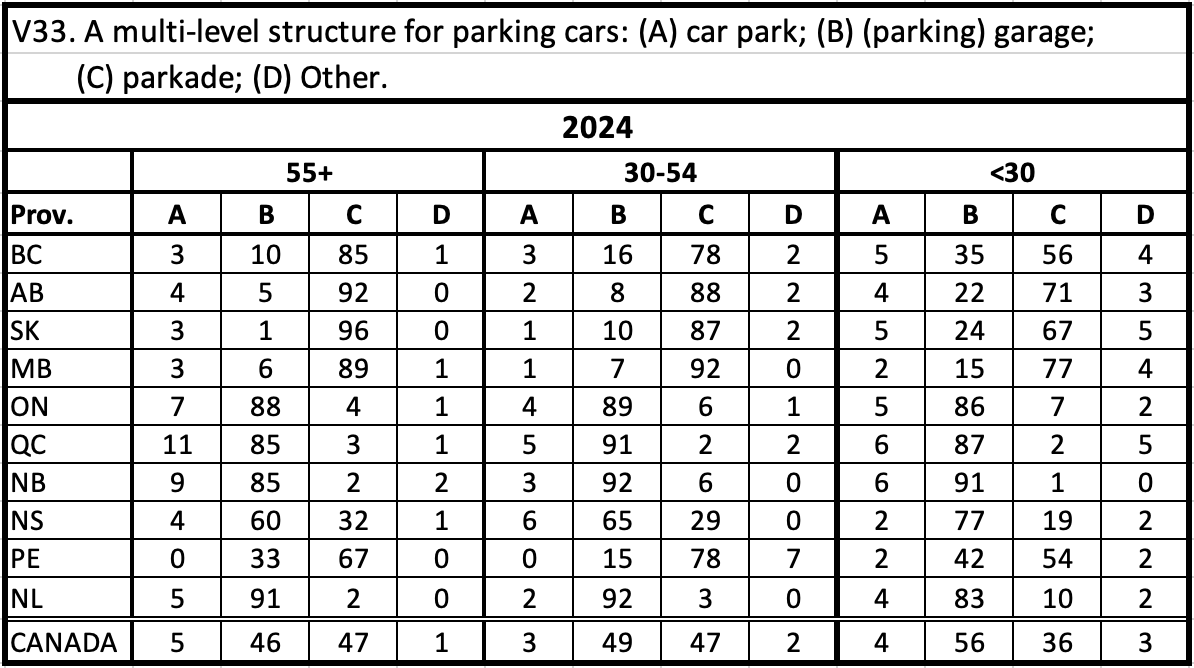

Like the words for athletic shoes and a small house in the countryside, those for a multi-level parking structure divide Western Canada from the rest of the country. West of Ontario, this is called a parkade, a term that likely originated as a trademark for the parking structures attached to department stores belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company, which were originally found only in Western Canada (‘the Bay Parkade’). The Bay’s department stores later spread eastward to Ontario and beyond, but not the word parkade, except, curiously, to Prince Edward Island and to a lesser extent Nova Scotia. From Ontario to New Brunswick, as well as in Newfoundland, we find the most common American term, parking garage, which is also now making inroads in Western Canada among younger respondents.

Age-based variation today

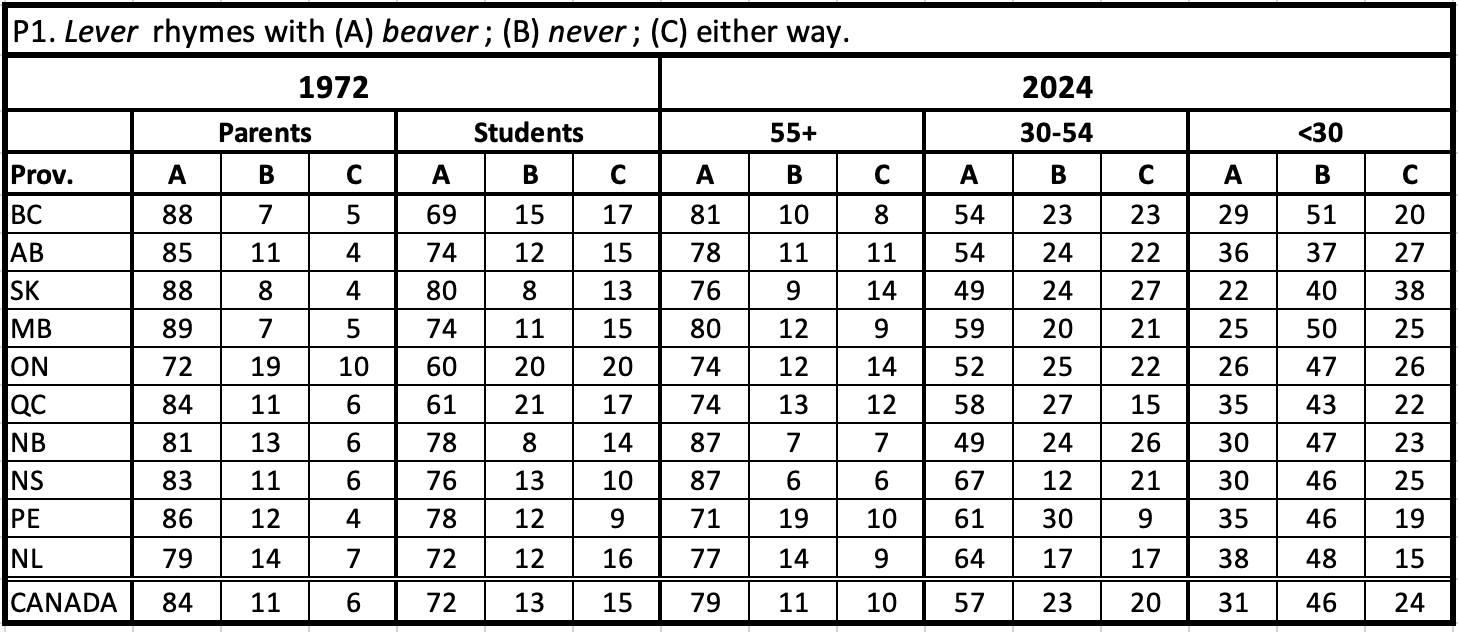

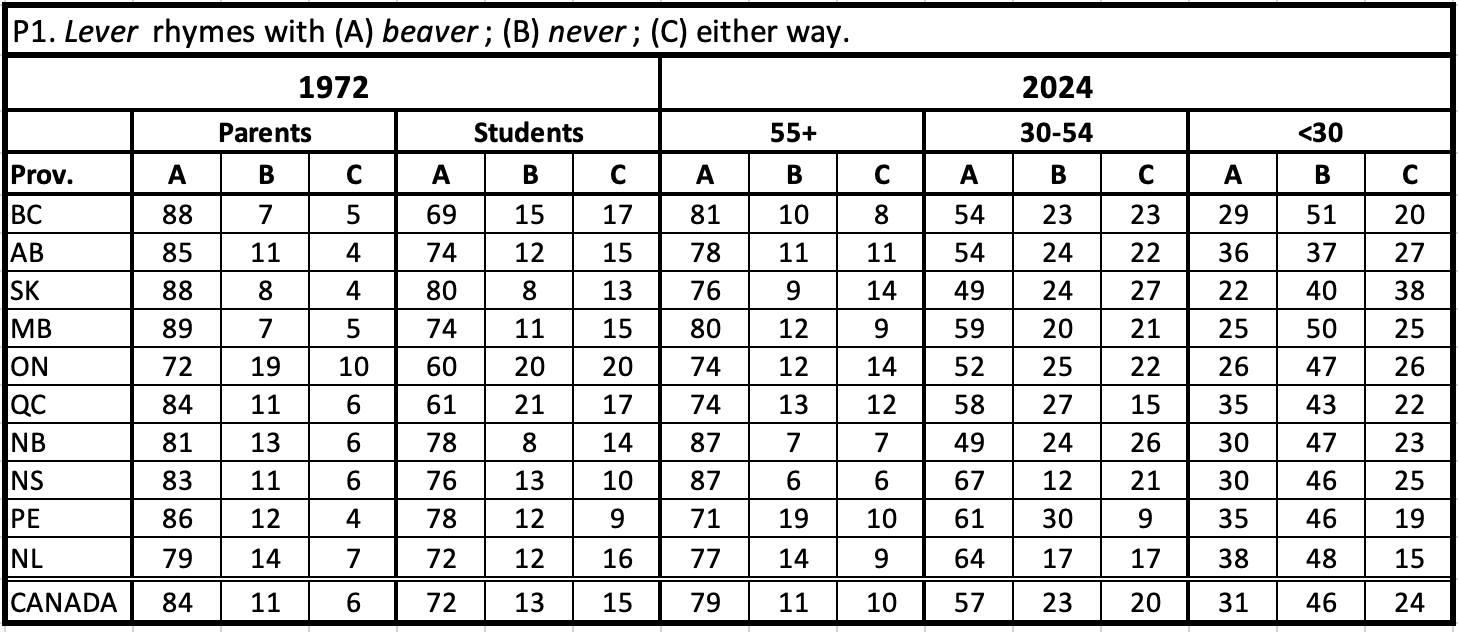

P1. Lever rhymes with beaver or never?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 51, Q8)

Oxford gives only the beaver pronunciation, making that the British standard, whereas Webster gives both variants but with the never pronunciation first, suggesting that is more common in American English. In 1972 (51, Q8), both parents and students inclined strongly toward the British beaver variant, but in 2024 that gradually gives way to the more American never variant: beaver declines from 79% to 31%, while never increases from 11% to 46%, becoming the dominant form in modern Canadian English.

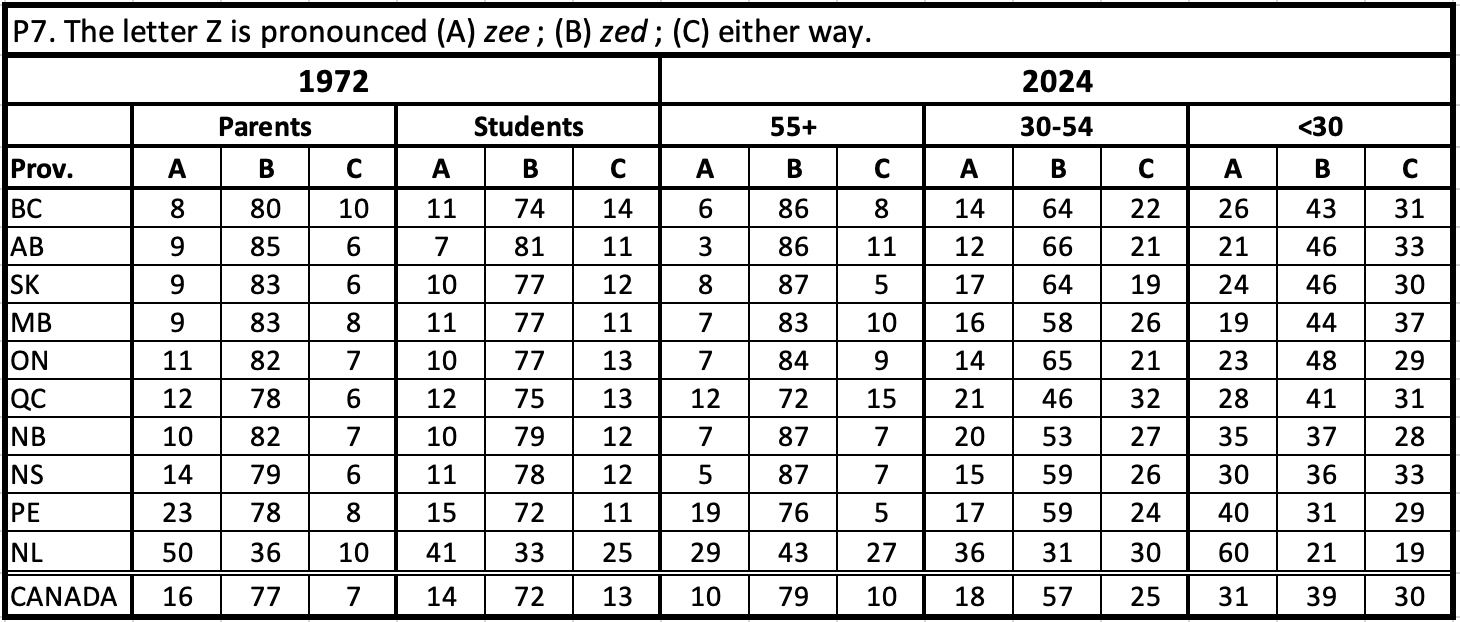

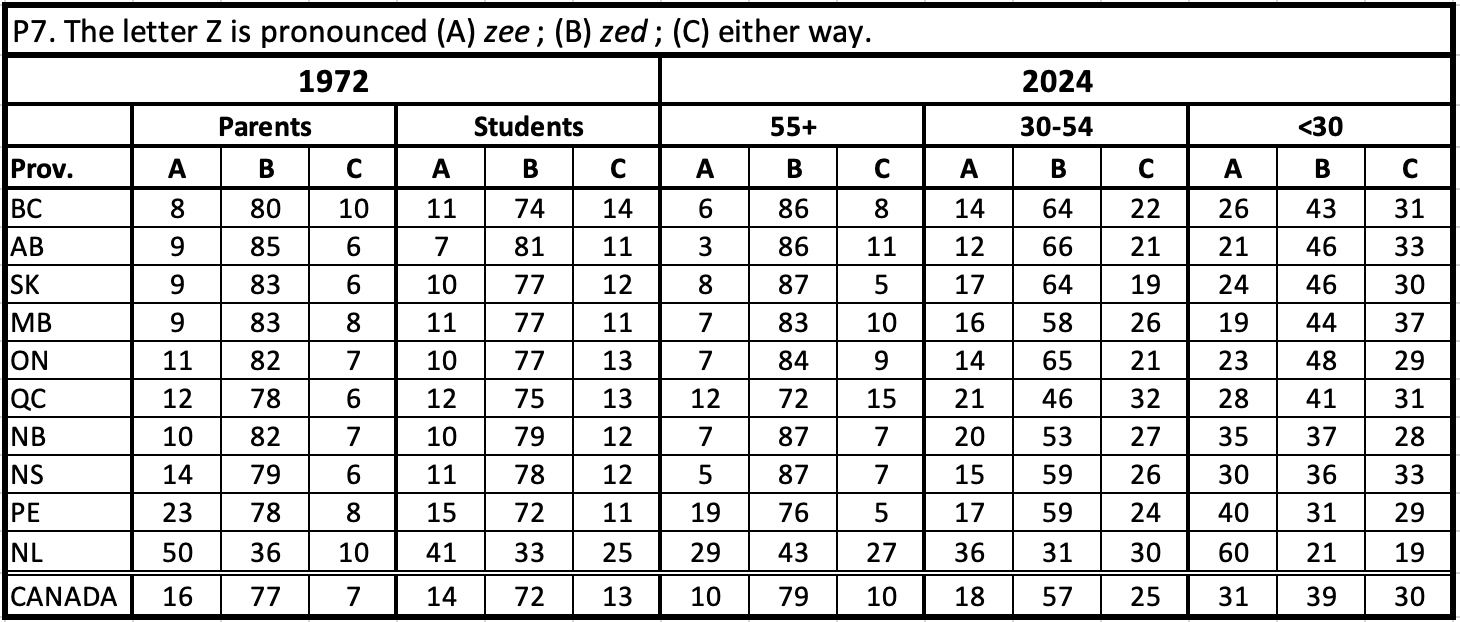

P7. The last letter of the alphabet is zed or zee?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 54, Q33)

There could hardly be a more iconic difference between British and American English, or symbol of Canadians’ orientation toward one standard or the other, than zed and zee. Notwithstanding the many similarities between Canadian and American English, Canadians have traditionally aligned strongly with British English on this question: Avis, who treats this as a pronunciation variable, reports that 93% of his Ontario respondents chose zed (1956:50). In 1972 (54, Q33), zee rises to around 15%, but zed still dominates everywhere except Newfoundland, where zee is the majority form. In the new data, however, we see a steady rise of zee, from 10% among the oldest respondents to 31% among the youngest, with zed declining correspondingly, from 79% among the oldest to 39% among the youngest, with another 30% of young people saying “either way” is okay. Newfoundland is again the leader in zee-usage, but our oldest Newfoundlanders show a preference for zed, like the rest of the country; it is among the youngest Newfoundlanders that zee attains clear majority status (60%). Atlantic Canada generally, in fact, shows a higher preference for zee than the rest of the country, whereas the strongest bastion of zed, among younger people, is on the Prairies and in Ontario.

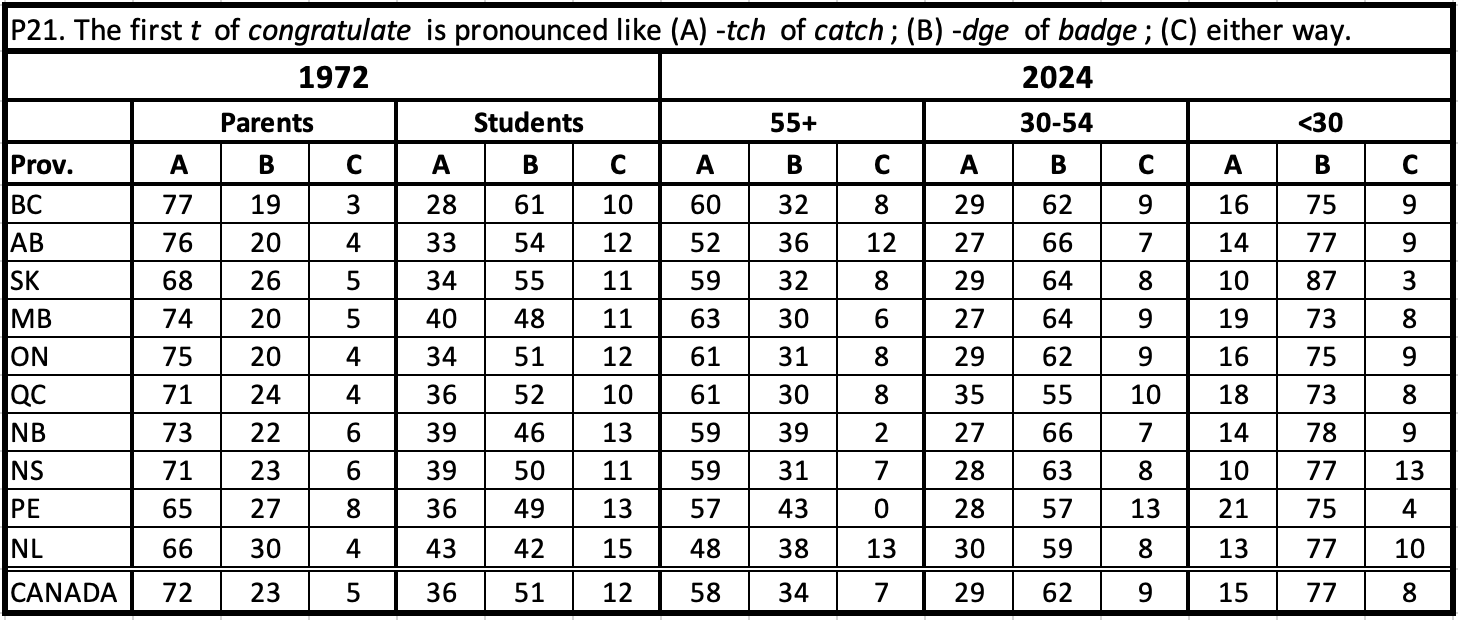

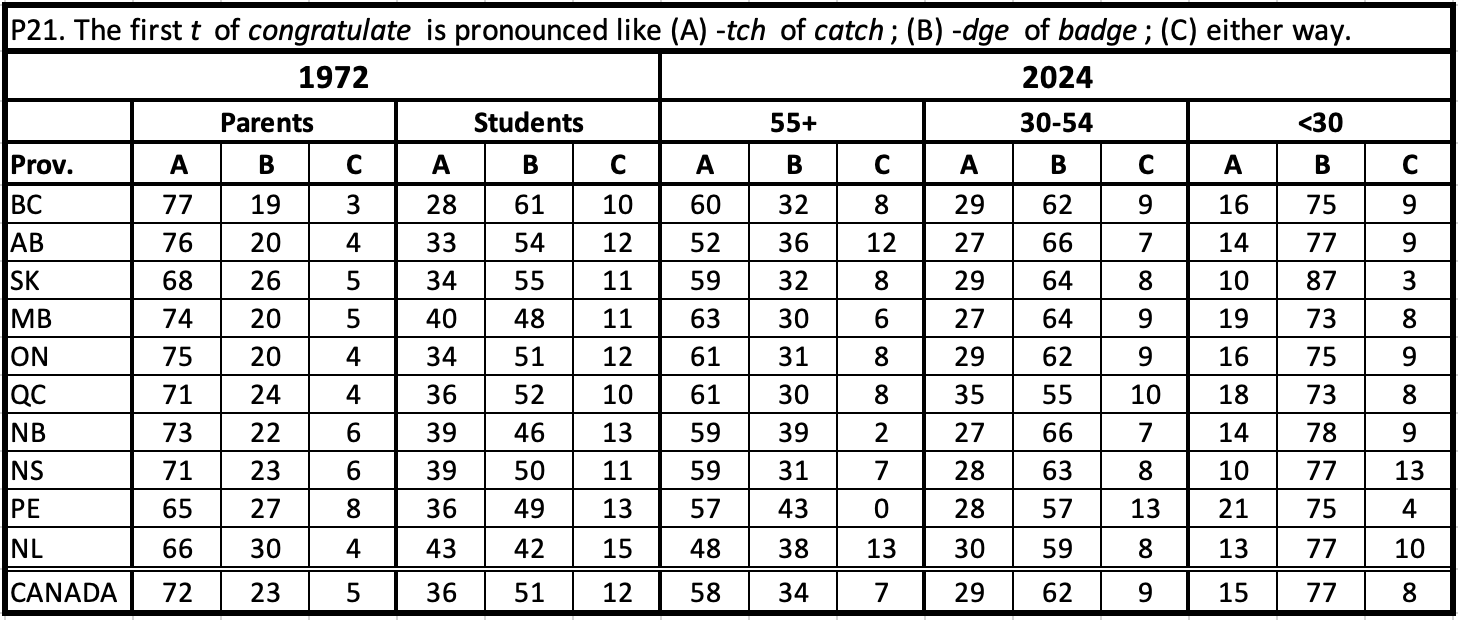

P21. Congratulate like catch or badge?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 69, Q101)

Oxford gives only con-GRATCH-ulate, while Webster allows con-GRADGE-ulate as a second variant. The original study showed a shift from a clear preference for the catch-like pronunciation among parents to a fairly strong preference for the badge-like variant among students (1972:69, Q101). The 2024 data show the same trend at a later stage: the catch variant declines from 58% of the oldest respondents to 15% of the youngest, while the badge variant increases from 34% of the oldest to 77% of the youngest, a dramatic reversal.

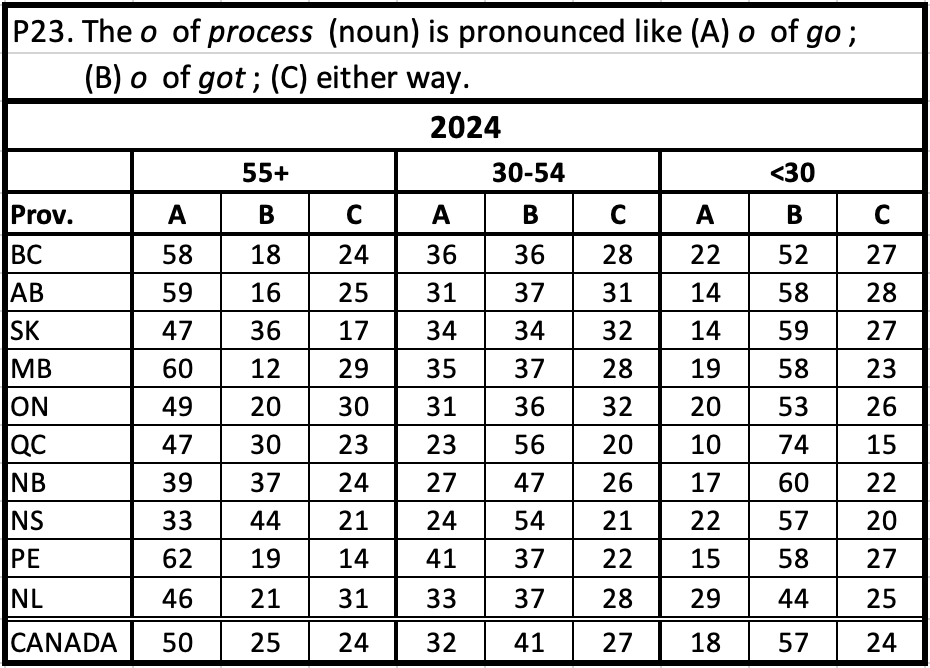

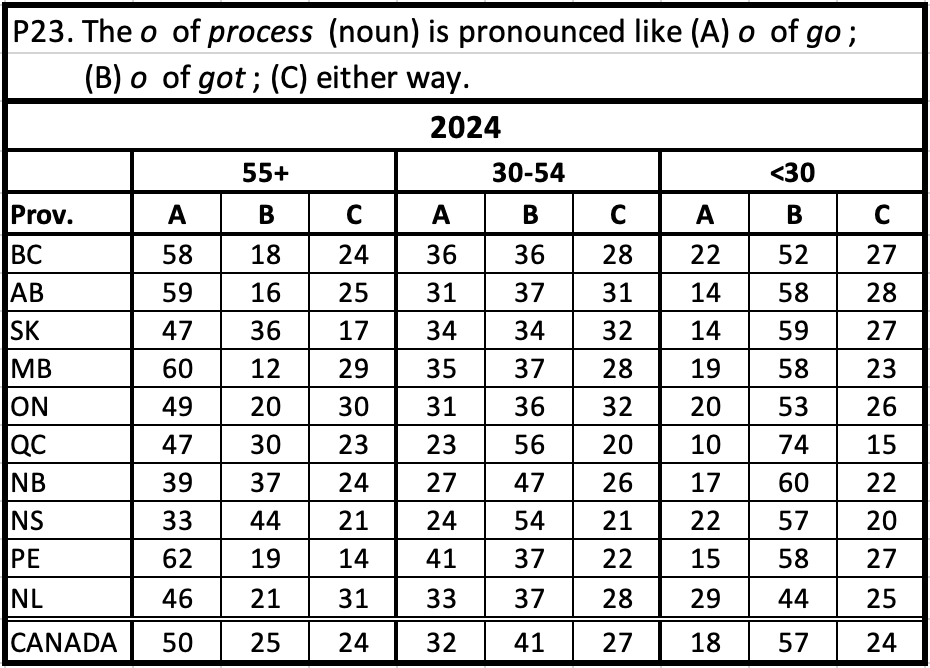

P23. The o of process (noun) is pronounced like go or got.

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 87%, B 13% (p. 45)

Variation in the pronunciation of this word is similar to that of progress, discussed above: Oxford gives only the go variant; Webster suggests the go variant is less common in American English but does not go so far as to label it British. Avis (1956: 45) shows an even stronger preference for the go variant in this word among Ontarians: 87%. It was not investigated in the 1972 survey, but our new data show a dramatic decline in the British pronunciation since the 1950s, from 50% among the oldest respondents to only 18% today; 57% of our youngest respondents now prefer the American got variant and a quarter say either is acceptable.

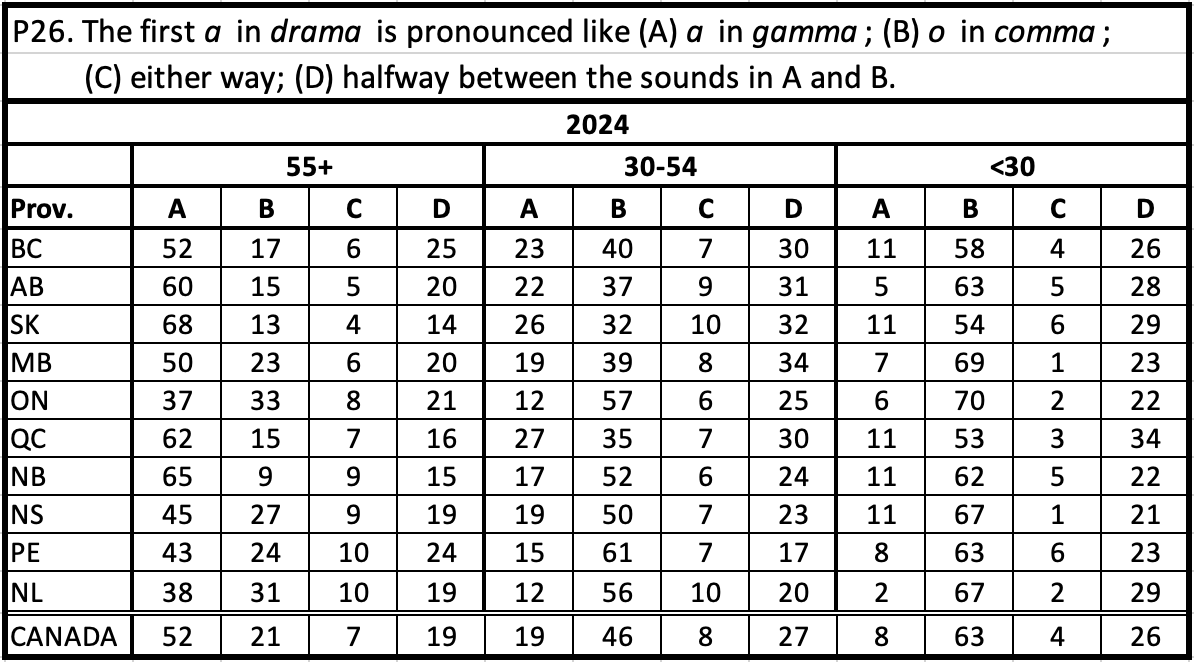

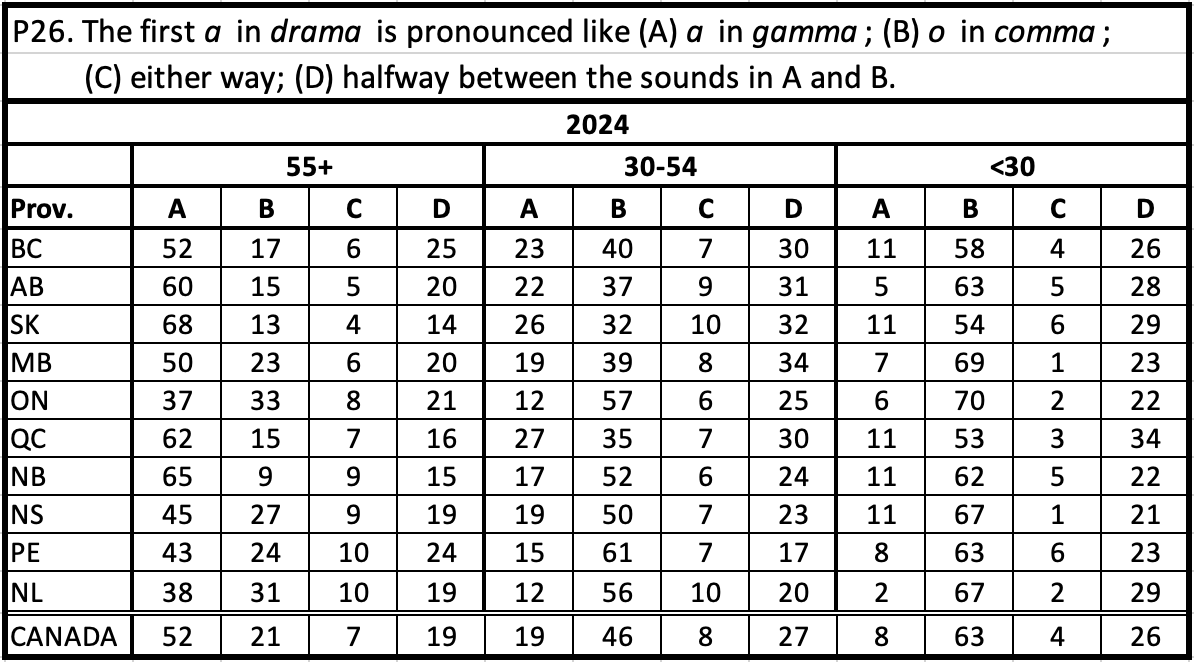

P26. Drama rhymes with gamma or comma?

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 83%, B 17% (p. 52)

Drama is one of many words of foreign origin in which the stressed vowel is spelled with the letter a and can therefore vary between the /æ/ sound of trap and the /ah/ sound of palm. There are three national patterns for pronouncing such words: Americans tend to use the /ah/ sound for most of them; British English chooses between the two sounds based on the length of the vowel, with /ah/ for long vowels (like drama) and /æ/ for short vowels; and Canadians, at least traditionally, tended to use the /æ/ sound in most of these “foreign (a)” words. That’s what Avis reports in the 1950s: 83% of his participants chose the /æ/ sound for drama, making it rhyme with gamma (1956: 52). This variable was not examined in 1972, but the 2024 data show a dramatic shift away from that traditional Canadian pronunciation: the preference for /æ/ declines steadily from 52% of the oldest participants to 19% of the middle group to only 8% of the youngest, while the British and American pronunciation with /ah/, which for Canadians rhymes with comma or trauma, increases correspondingly from 21% to 46% to 63%, though about a quarter of respondents suggest that the vowel of drama is really halfway between the two qualities.

G5. He has drank/drunk three glasses of milk.

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 77, Q28)

In modern standard English grammar, the past tense of drink is drank (“I drank a glass of milk for lunch today”), while the past participle is drunk (“I have drunk milk since I was a child”); this is one of many ‘ablaut’ or vowel-change patterns found in the paradigms of Germanic ‘strong’ verbs (compare German trinken-trank-getrunken, or other English verbs, like sing-sang-sung, sink-sank-sunk and swim-swam-swum, with the same vowel changes as drink). Throughout the history of English, however, there has been variation in the use of drank and drunk as past and participle forms and that variation continues today. In the 1950s, Avis records most Ontarians preferring the standard has drunk, which he labels British, but one third preferring non-standard has drank, which he labels Northern American (1955:19). In 1972 (77, Q28), if the published results are correct, the proportions appear to have reversed: about 60% of both parents and students chose drank. In 2024, the oldest group reverts to the earlier pattern of Avis’ data, with about two-thirds choosing drunk, but the preference evens out among the middle group and then shifts strongly to drank among the youngest group (70%), with only 21% using the grammatically correct form drunk.

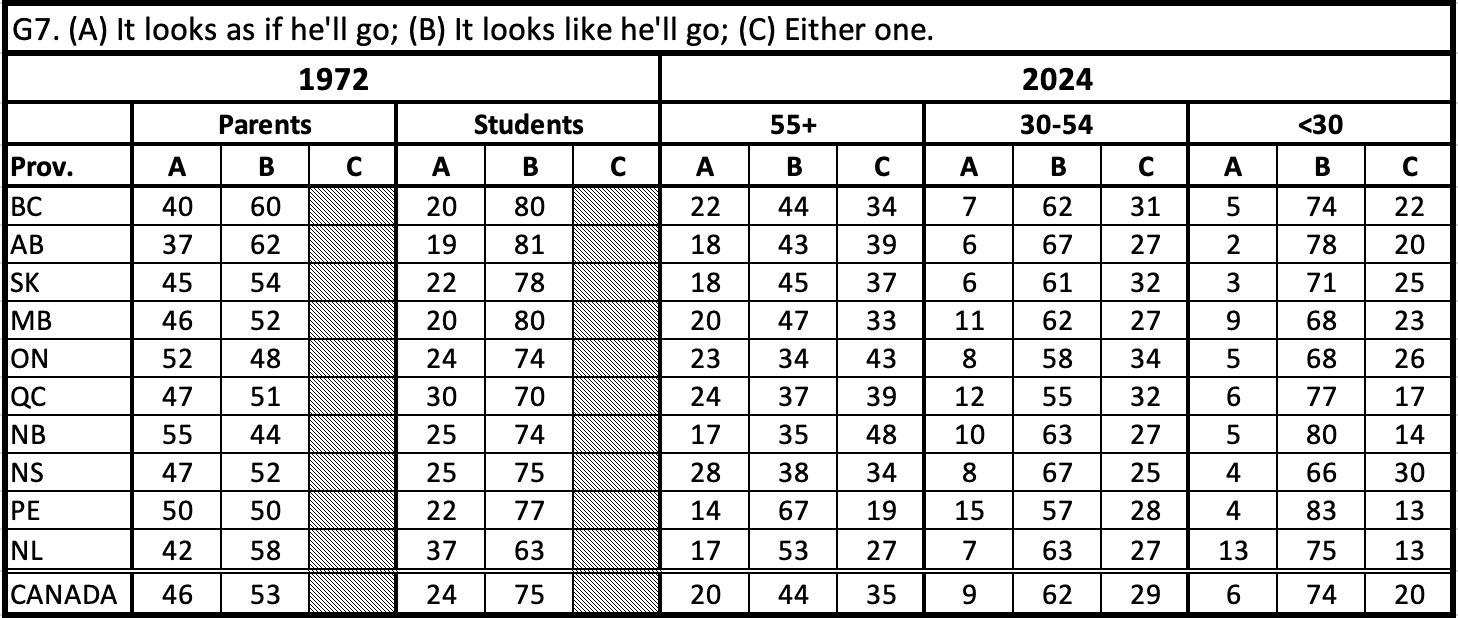

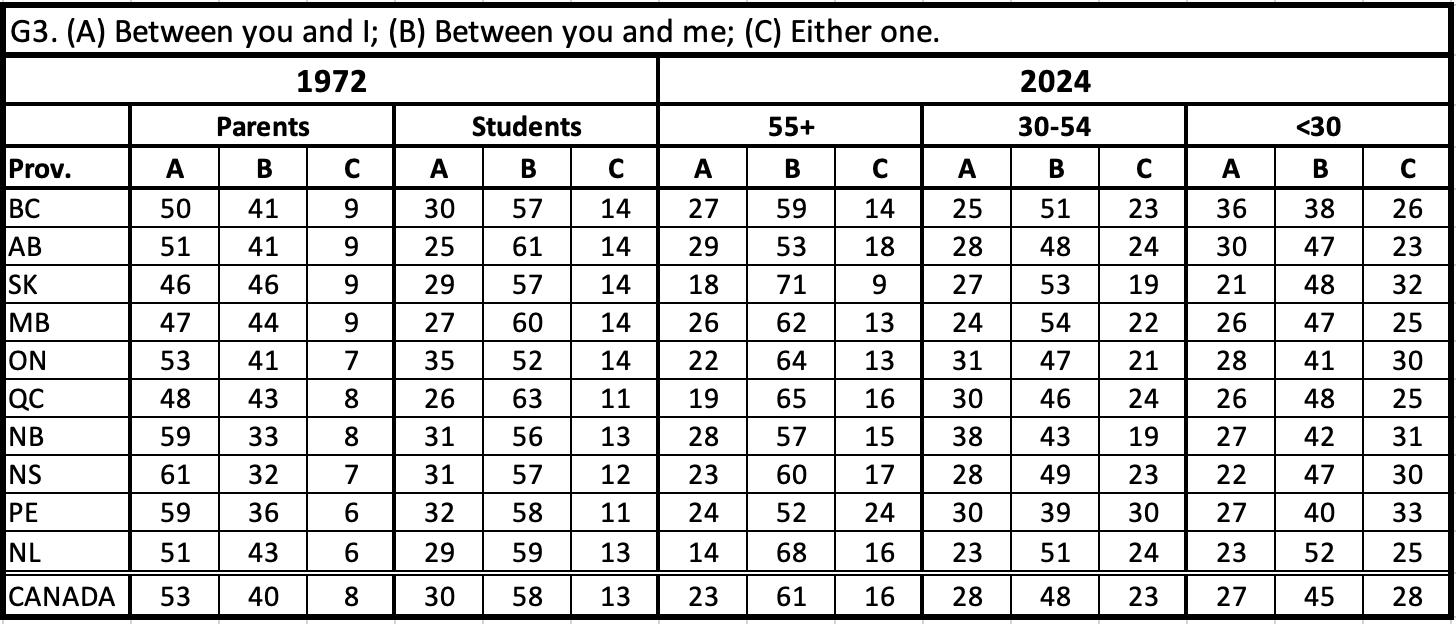

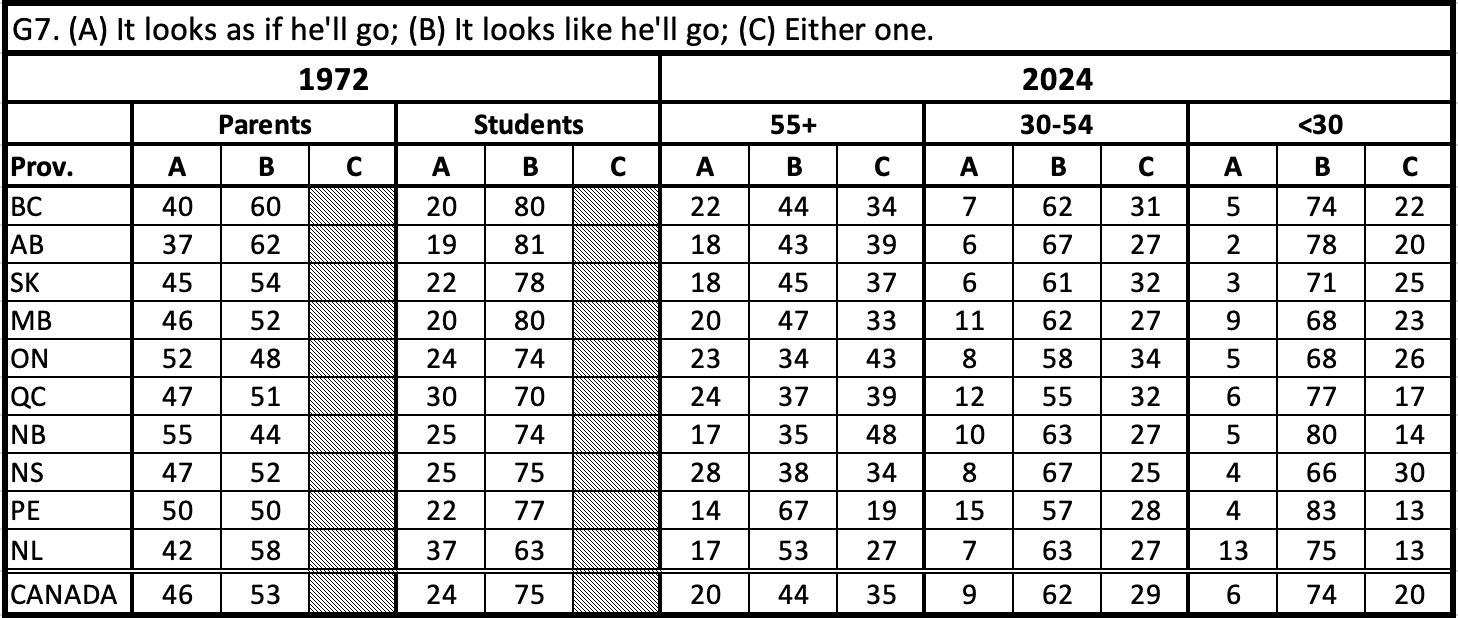

G7. It looks as if/like he’ll go.

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 80, Q46)

Formal standard English tends to prefer as if to like before subordinate clauses (“she looks as if she’s ready to leave”), whereas like introduces nouns (“she looks like a nice girl”), but the use of like before subordinate clauses is now common. In the 2024 data, preference for like increases from 44% of the oldest respondents to 74% of the youngest, while as if declines correspondingly from 20% of the oldest to only 6% of the youngest. Apparently, “it looks as if it’s going to rain” now sounds formal; most people say, “it looks like it’s going to rain.”

V4. Rain-catchers along the roof of a house are eavestroughs or gutters?

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 99, Q108)

These structures are called gutters in both British and American English: Webster’s entry for eavestrough redirects to gutter and Oxford omits it entirely. Like chesterfield and scribbler, eavestroughs is therefore a true Canadianism: it was used by 73% of the parents in 1972 (99, Q108), though less consistently in Atlantic Canada, where gutters was more common in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Among students, however, preference for eavestroughs, at only 49%, was already giving way to acceptance of both terms, which grew to 23%. The new data show the continued decline of eavestroughs, from 75% of the oldest group to 60% in the middle group and only 34% in the youngest group, who have shifted strongly to gutters (62%). Regional variation persists as well, with eavestroughs hanging on as the dominant term, even among young people, on the Prairies and in Ontario, but close to vanishing in British Columbia, Quebec and Nova Scotia.

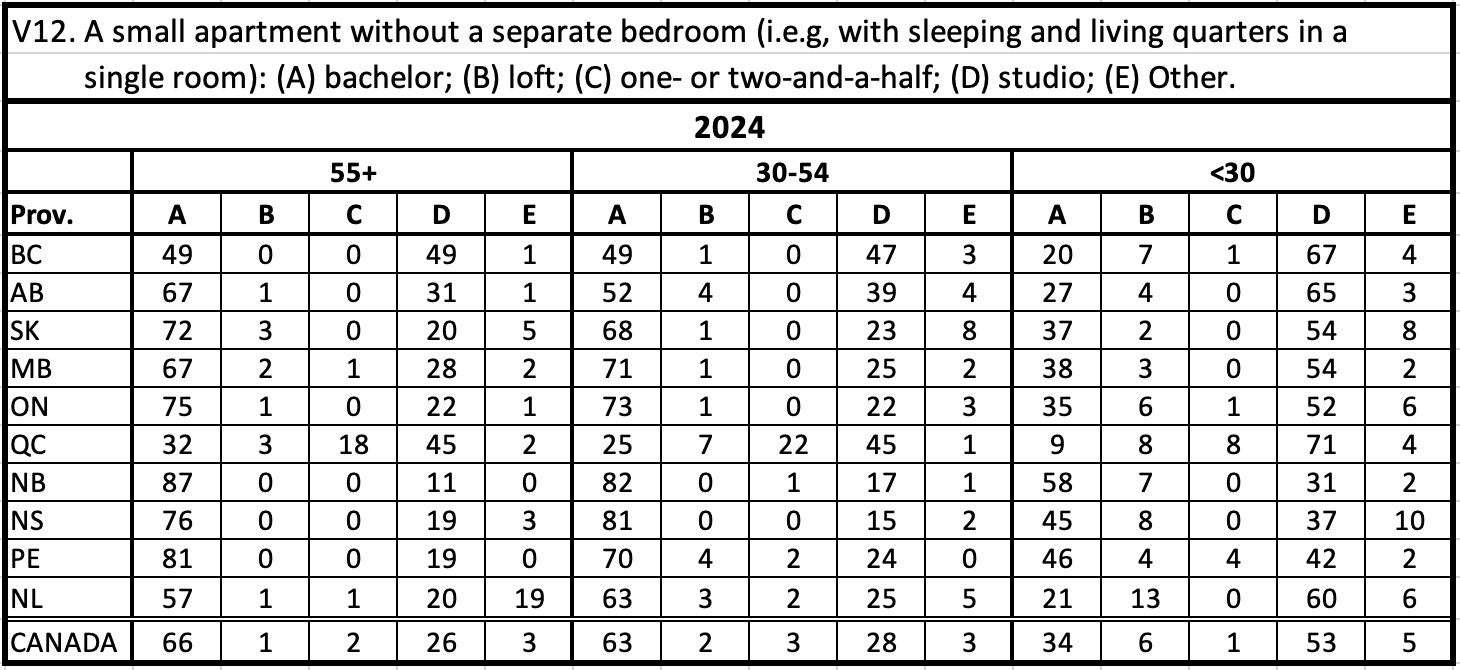

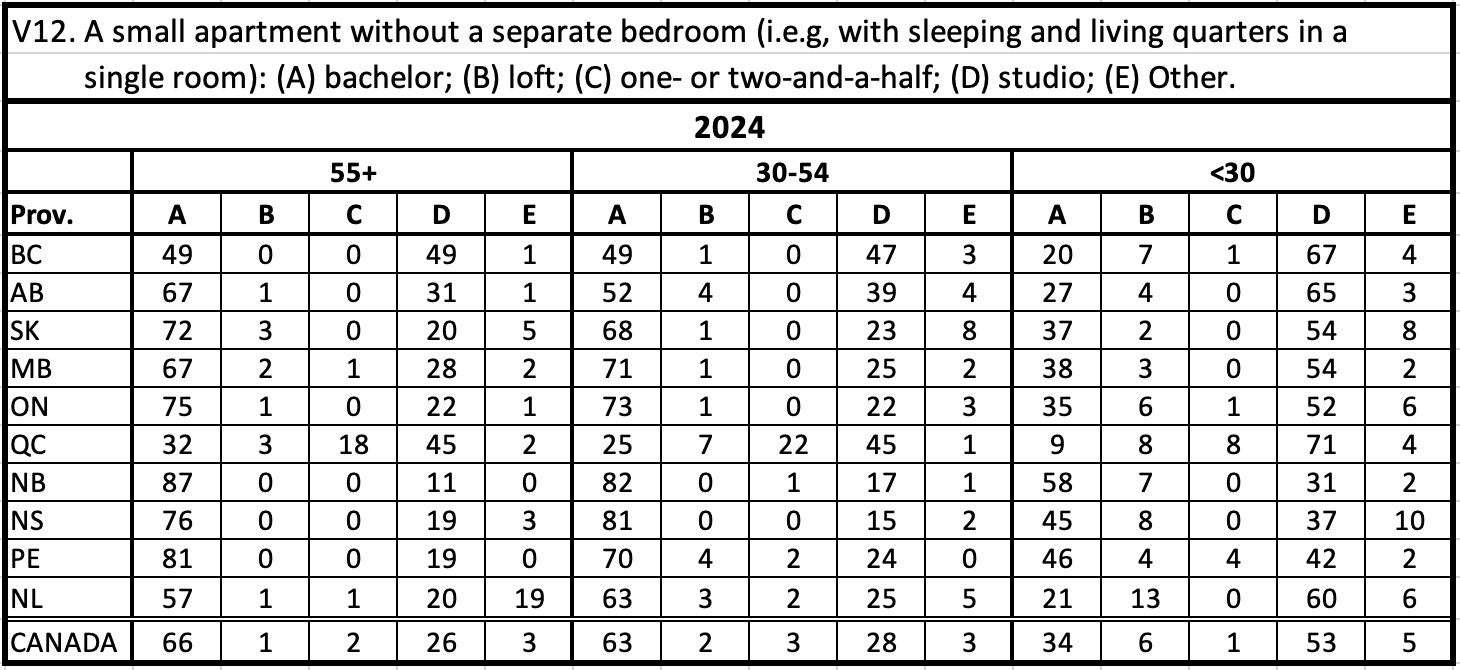

V12. A small apartment without a separate bedroom is a bachelor, a loft or a studio?

Note: Newfoundland "other" is mostly bed sitter/bed sitting

Among older Canadians outside Quebec, a small apartment without a separate bedroom is called a bachelor apartment or bachelor suite, a euphemism that suggests the sort of place where a single young man might live before getting married and buying a house. This term was particularly dominant in Saskatchewan, Ontario and the Maritimes, but in Quebec it competes with a nomenclature borrowed from French, which classifies apartments based on the number of rooms, with the bathroom counting for half: depending on whether the apartment had a separate kitchen, it would therefore be called a one-and-a-half or a two-and-a-half, whereas what Canadians outside Quebec call a one-bedroom apartment would be a three-and-a-half. Americans use a different euphemism, studio, suggesting an artist’s workspace. Yet another euphemism, loft, suggesting converted Greenwich Village or SoHo warehouse or factory spaces (rather than haylofts), has recently gained popularity as well, but still has a minimal presence in Canada. The non-Quebec Canadian use of bachelor holds steady in the middle age group (63%) but drops to half that level among the youngest respondents (34%), who have shifted strongly toward the American studio (53%); this shift is seen even in Quebec, where studio (71%) has largely replaced one- or two-and-a-half (8%). Among younger respondents, bachelor hangs onto its dominant position only in the Maritimes, but use of studio has doubled there, as well.

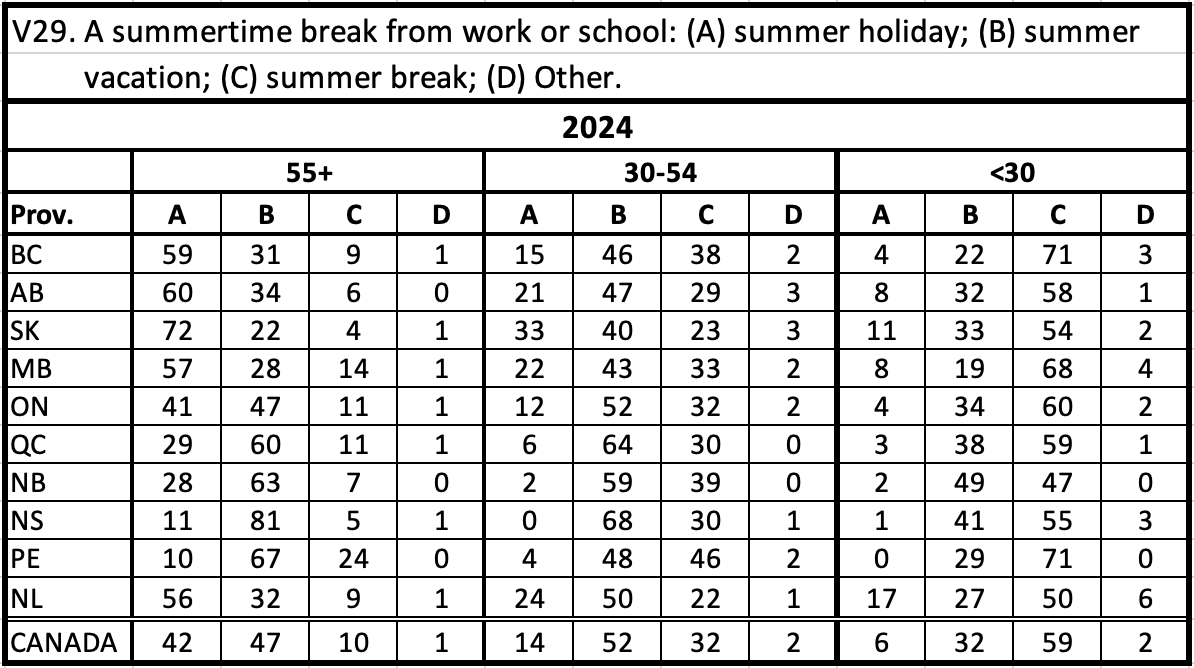

Holiday originally meant a holy day in the church calendar, when people were excused from work, thus the Christmas or Easter holiday, whereas vacation, borrowed from Latin via French, meant more generally freedom or exemption from work, thus a week’s vacation in the summertime, often involving travel. This distinction is generally maintained in American English, with holidays being government-decreed days off for most workers and vacations being individually planned extended absences from work. Webster labels the use of holiday to mean vacation as “chiefly British”, while Oxford labels the word vacation “North American”, though some British university students refer to their summer break as the vac. Break is a third term that tends to be associated more with a break from school than other types of time off, as in Spring Break. In the new survey, when asked about a summertime break from work or school, the older participants are divided evenly between the main British and American terms, summer holiday (42%) and summer vacation (47%), with summer break a distant third choice (10%), though there are also regional differences, with holiday most popular in Western Canada and Newfoundland and vacation most popular in Quebec and the Maritimes. In the younger age groups, preference shifts strongly toward break, first away from holiday and then away from vacation as well: among the youngest participants, break is chosen by 59% and holiday by only 6%. This may partly reflect the large number of students among the youngest group, given the association of break with the school year.

Summary

Warkentyne (1971:195) explains that “one of the primary aims of the [original] Survey was to compare the speech of the young with that of their parents”, “to show how Canadian English is faring as generation gives way to generation.” Other than the five spelling variables, the 104 questions “were not designed to show American or British influence”, yet many of them do involve differences between British and American variants and this has understandably been a major preoccupation of linguists studying Canadian English, given its historical and present geographical and cultural context. The shifting balance between British, American and in some cases uniquely Canadian pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and spelling is, indeed, one of the most important ways English in Canada is changing between generations. The new survey reported here gives us a fifty-year perspective on this question – the span of about two generations – as well as a new set of data on how Canadian English varies today, both by region and between age groups.

Thanks to the history of English-speaking settlement in Canada, the kind of English we speak here has always entailed a mixture of American and British features. Its basically North American character was established by the United Empire Loyalists, refugees from the American Revolutionary War who established the first major English-speaking settlements in Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes in 1783-84, bringing colonial American English to British North America. In the first half of the 19th century, direct immigration from all over the British Isles added many regional dialects of British English, including Irish and Scottish English, to the Canadian mix.. Following the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway linking Montreal and Vancouver in 1885, the Canadian West was settled by an even greater diversity of migrants, with the largest groups coming from Britain, the United States, Europe and, most importantly, Eastern Canada; the latter group transplanted Eastern Canadian English, especially Ontario English, westward (see Boberg (2010: 55-105) for a detailed discussion of these settlement patterns).

As Canada’s primary political and cultural orientation gradually shifted from Britain, in the nineteenth century, to the United States, in the twentieth, the country and its language came under increasing American influence, aided by ever-improving communication technologies that broke down the barriers that isolated Canadians from such influence in the past. The recent Americanization of Canadian English, beyond its initial North American character, can be seen in the replacement of both British and unique Canadian pronunciations, grammatical forms and vocabulary with variants that are more common in American English. The variables discussed above provide several examples of each type: British forms at various stages of decline include dived and sneaked as the past tenses of dive and sneak, progress and process starting with pro-, lever rhyming with beaver, the catch-type pronunciation of congratulate, serviette as a term for napkin and zed as the last letter of the alphabet; declining Canadian words include bachelor apartment, chesterfield, eavestroughs, parkade and scribbler; the unique Canadian pronunciation of drama to rhyme with gamma is also on the way out, in this case converging with the form found in both British and American English. The major exception to Americanization is in spelling, where many Canadians still prefer British spellings like colour and centre, but it is uncertain whether this preference will continue in the future.

Warkentyne (1971: 197) cites several examples of regional variation in his report on the original survey, but admits that, “Clear-cut judgments on dialect boundaries within Canada are difficult to make from the Survey data. There is a tremendous overlapping of features from one area to the next, suggesting active diffusion. Perhaps an extension of the checklist to include many more known regionalisms would make the task much easier. However, this remains a task for the future.” This task has been the second major concern of the present survey, inspiring the addition of many new vocabulary variables that were not included on the original questionnaire. As shown above, these display a great deal of regional variation, involving many different patterns: Westerners say cabin, parkade and runners where Ontarians say cottage, parking garage and running shoes; Maritimers say bookbag, scribbler and the works where other Canadians say backpack, notebook and deluxe; Quebeckers use unique words like all-dressed, dépanneur, chalet, one-and-a-half and soft drink. These regional divisions were identified in previous work by Boberg (2005, 2010, 2016), but are supported in the present study by more data and more variables. Along with age-based variation in the new data, they will be explored in future journal articles now in preparation.

The Data

Following is a list of the 85 survey questions, each linked to its corresponding data table (click on the question to see the table). The variables or questions are listed in the order in which they appear in the new questionnaire, where they are grouped into four categories: pronunciation (P), grammar (G), vocabulary (V) and spelling (S). The tables show the frequency of each variant, or response category, for each provincial and generational group, as a percentage of the total responses in that group. Where 1972 data are available for comparison, these are shown to the left of the 2024 data. To highlight regional differences more effectively, the 1972 frequencies are an average of the male and female frequencies for each province-age group presented in the original report. Where 1950s data are available from Avis’ survey of Ontario speech, these are given in text form under the new data.

Pronunciation Questions

P1. Lever

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 51, Q8)

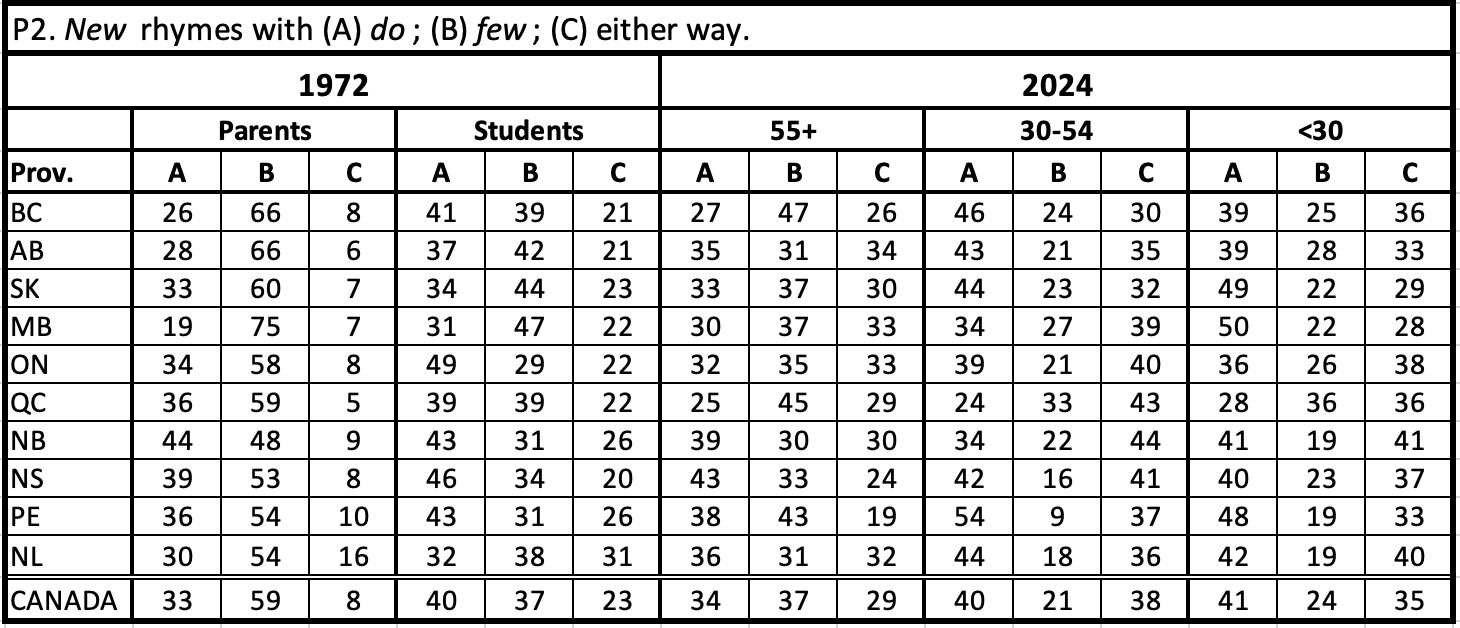

P2. New

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 51, Q14)

P3. Student

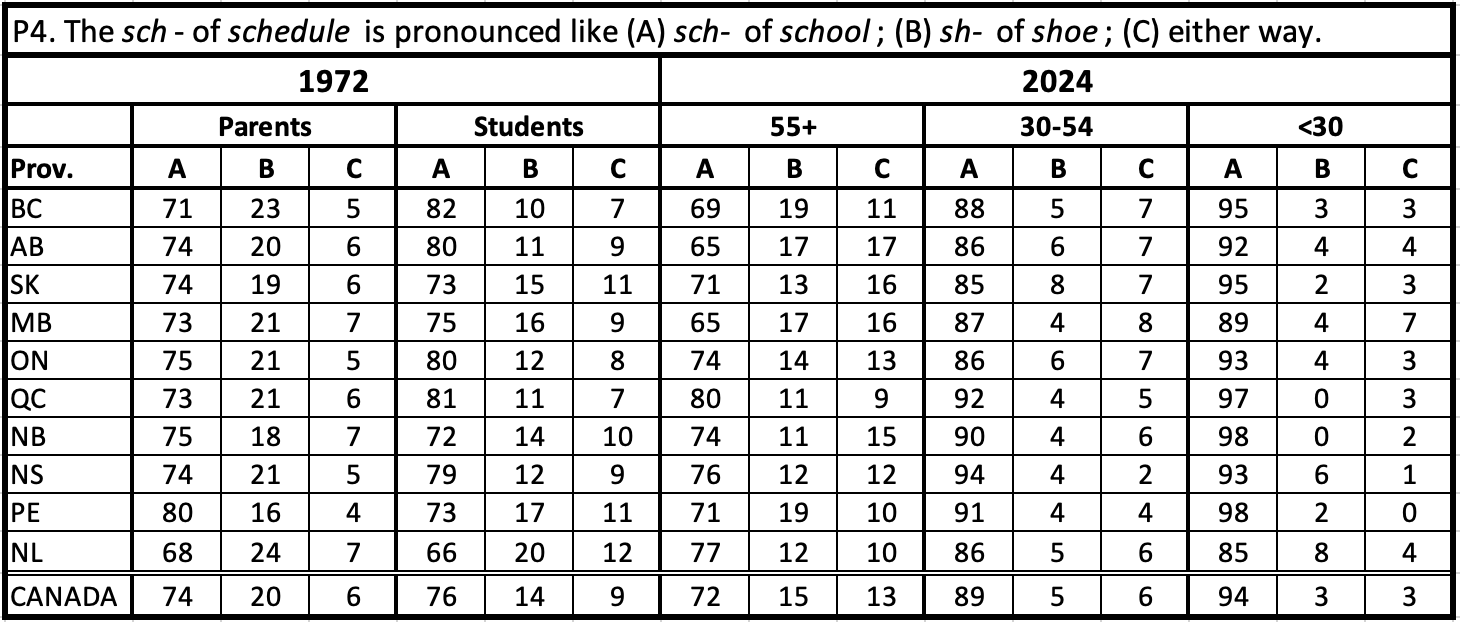

P4. Schedule

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 53, Q20)

P5. Genuine

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 53, Q26)

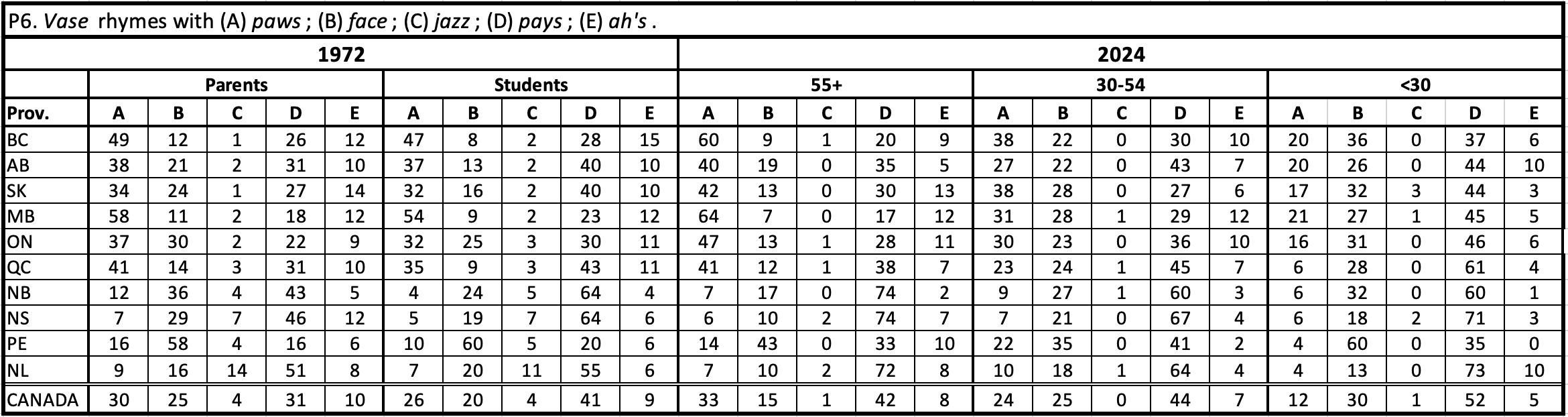

P6. Vase

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 54, Q27)

P7. The letter 'Z'

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 54, Q33)

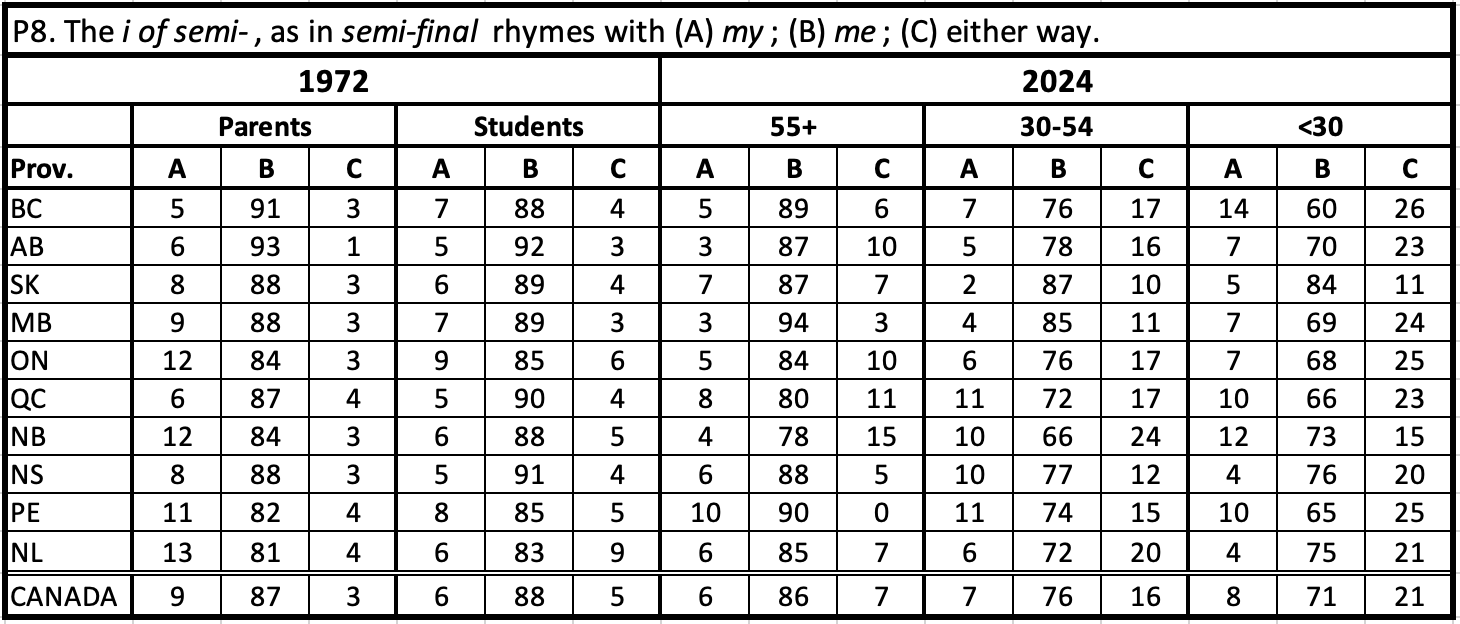

P8. The prefix semi-

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 55, Q37)

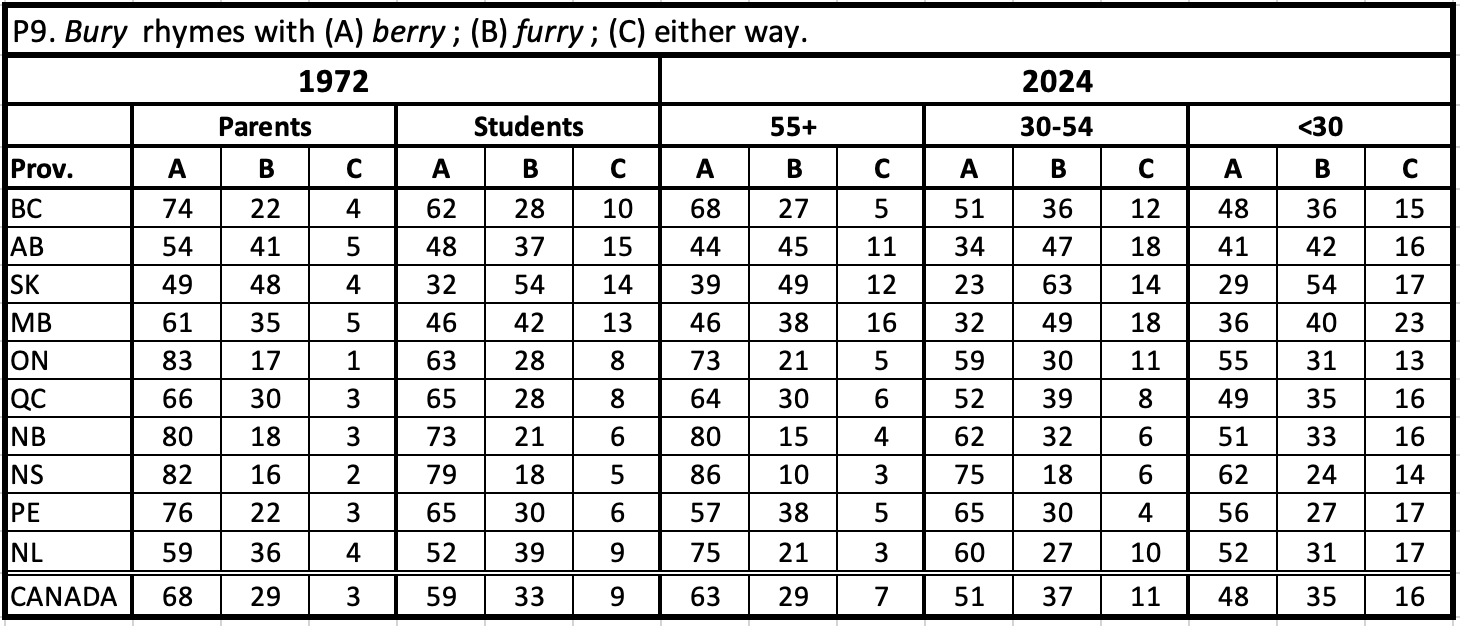

P9. Bury

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 41, Q56)

P10. Arctic

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 56, Q42)

P11. Again

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 60, Q59)

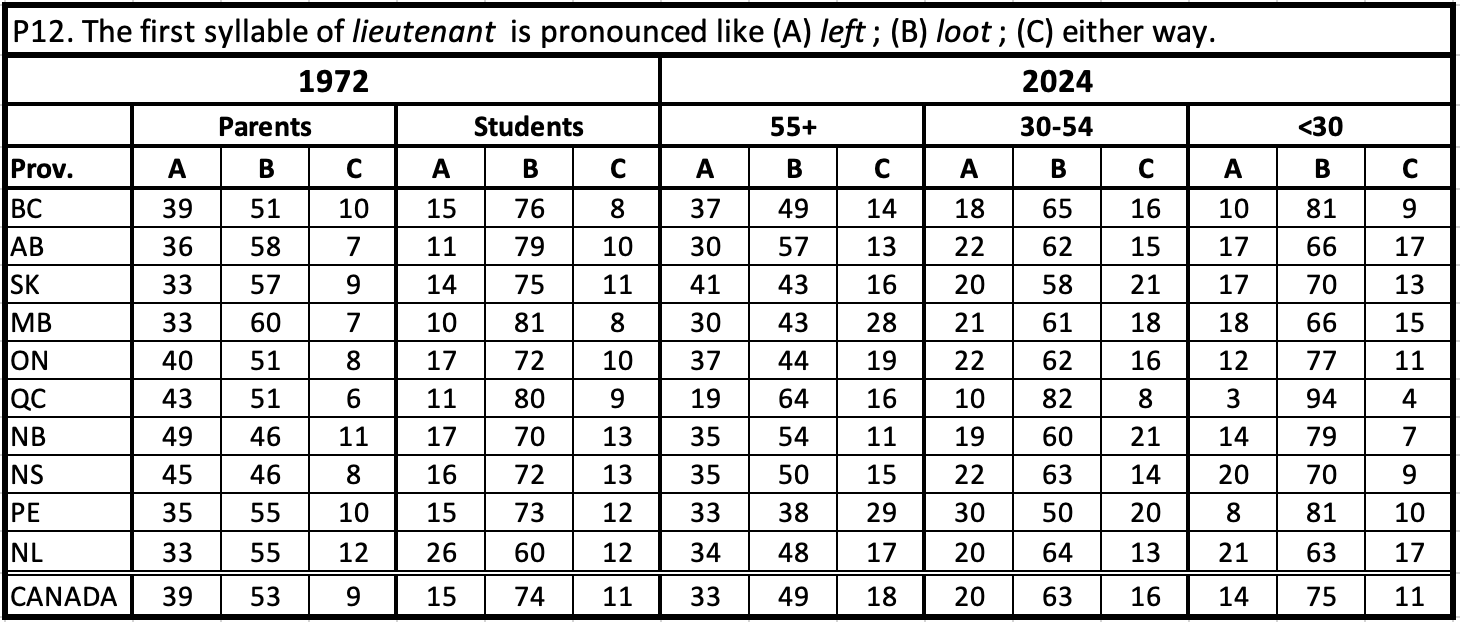

P12. Lieutenant

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 61, Q62)

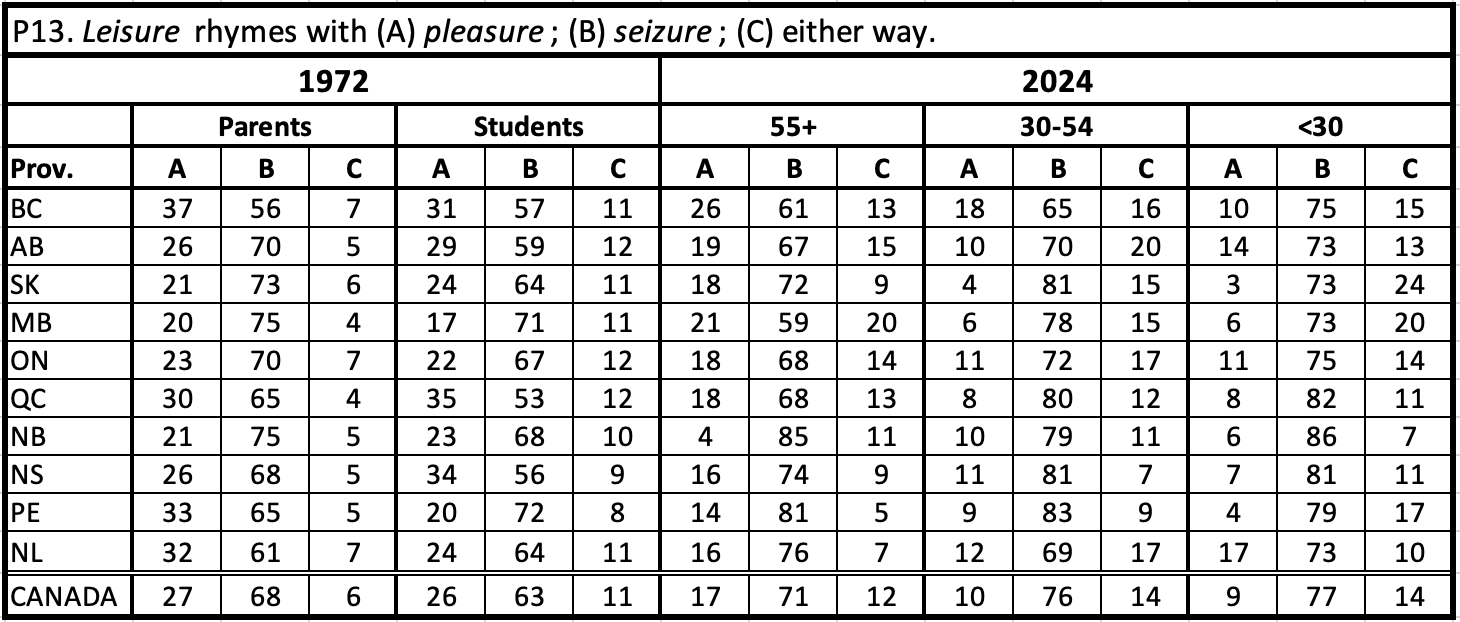

P13. Leisure

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 61, Q66)

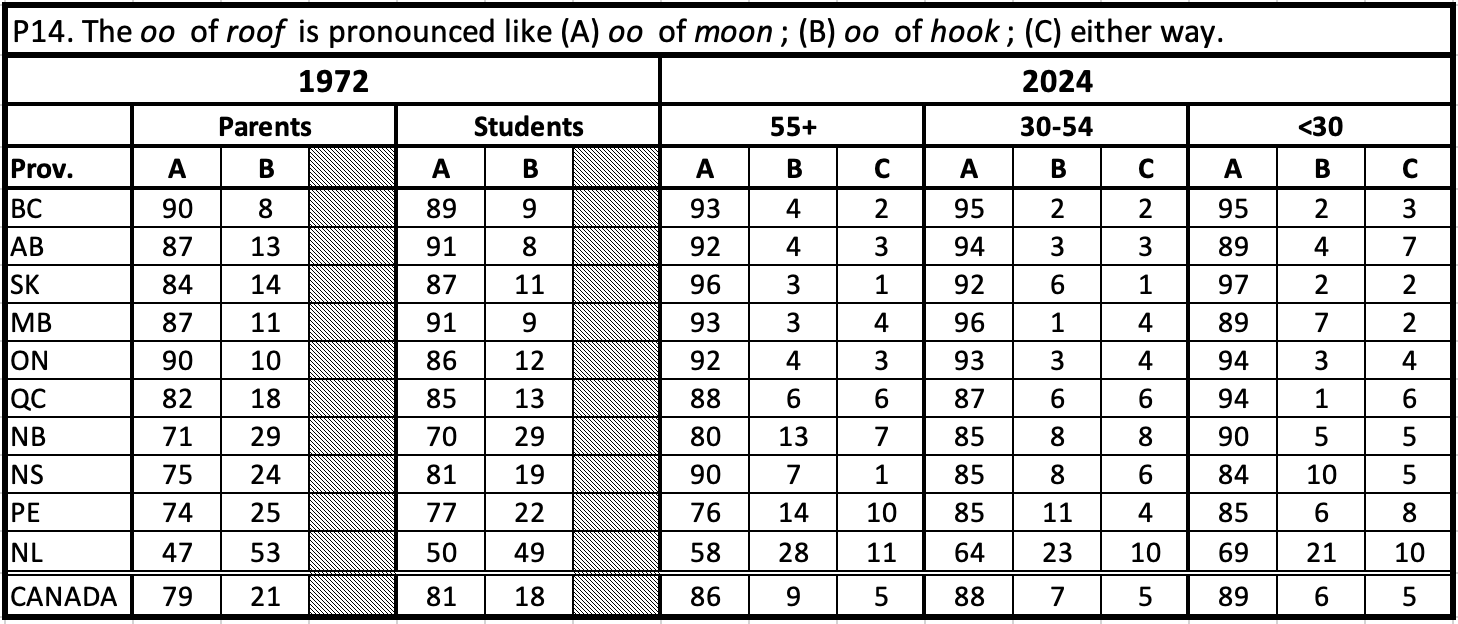

P14. Roof

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 62, Q72)

P15. Either

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 63, Q77)

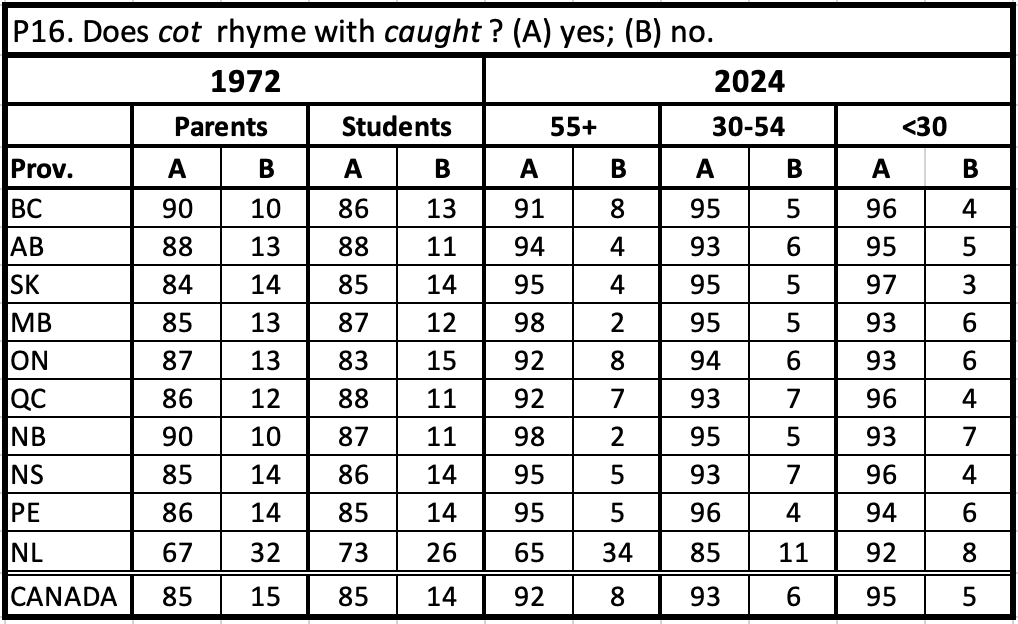

P16. Cot vs Caught

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 64, Q78)

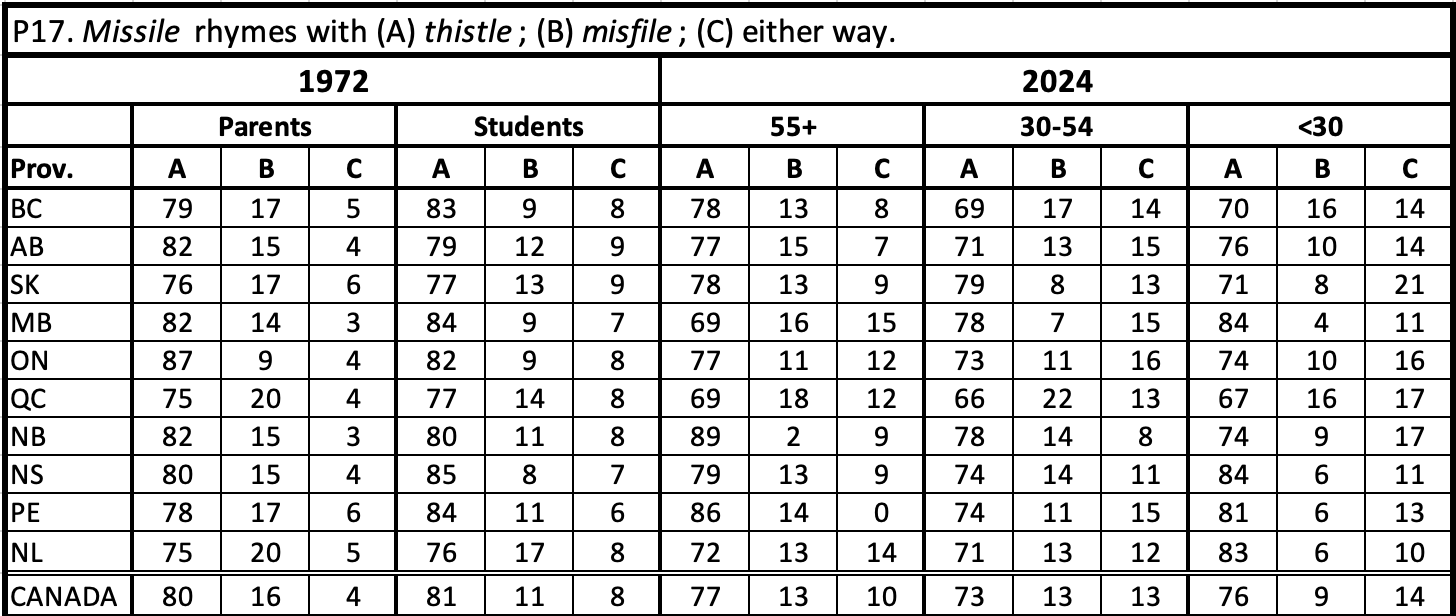

P17. Missile

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 64, Q81)

P18. Almond

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 67, Q88)

P19. Progress

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 67, Q91)

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 66%, B 34% (p. 45)

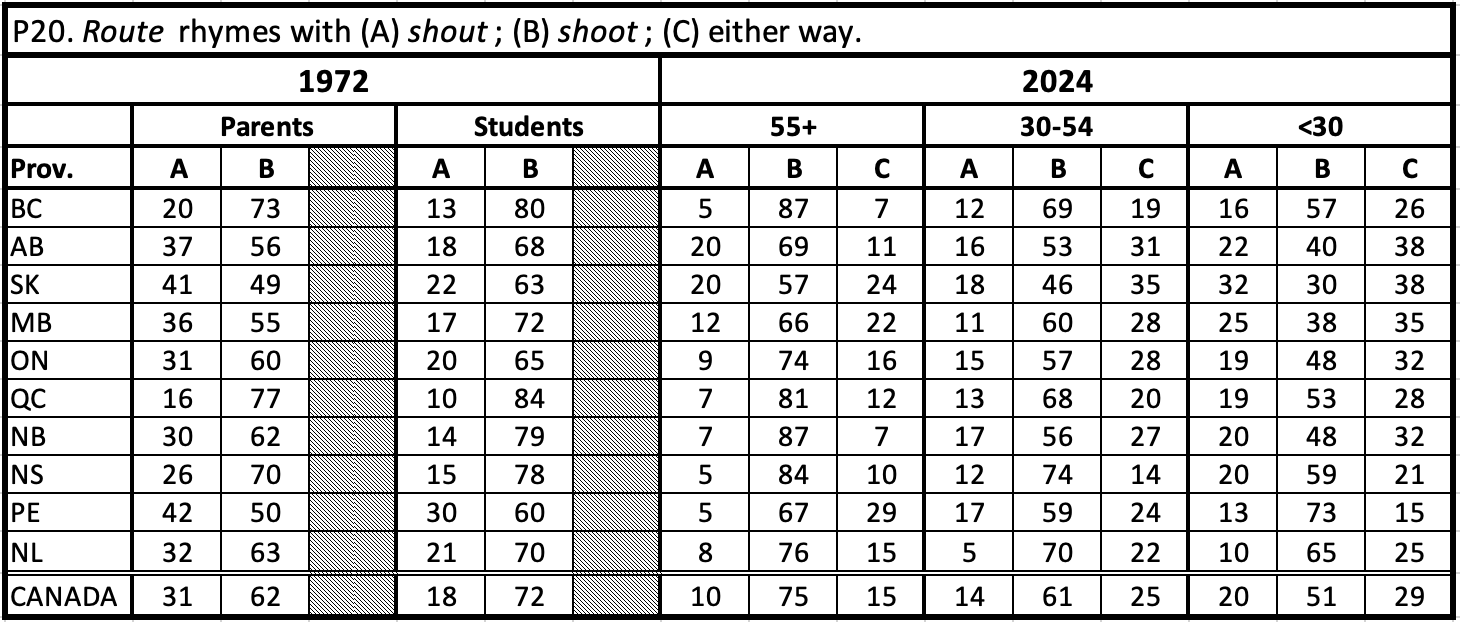

P20. Route

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 68, Q93)

P21. Congratulate

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 69, Q101)

P22. Which/Whine vs Witch/Wine

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 71, Q106)

P23. Process

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 87%, B 13% (p. 45)

P24. Fertile

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 59%, B 41% (p. 46)

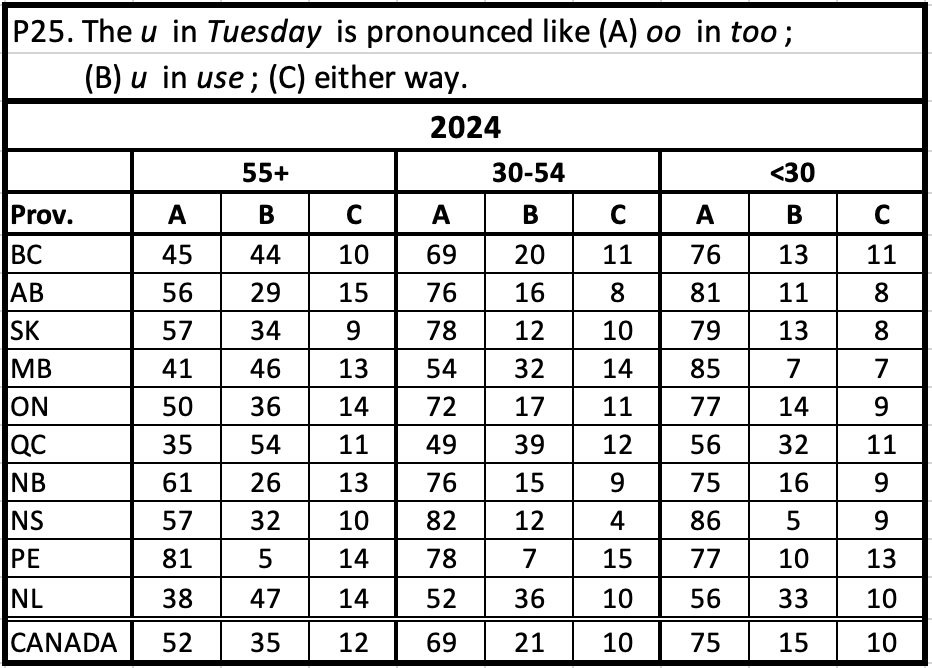

P25. Tuesday

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 37%, B 63% (p. 48)

P26. Drama

Avis (1956) Ontario data: A 83%, B 17% (p. 52)

Grammar Questions

G1. Dove vs Dived

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 72, Q23)

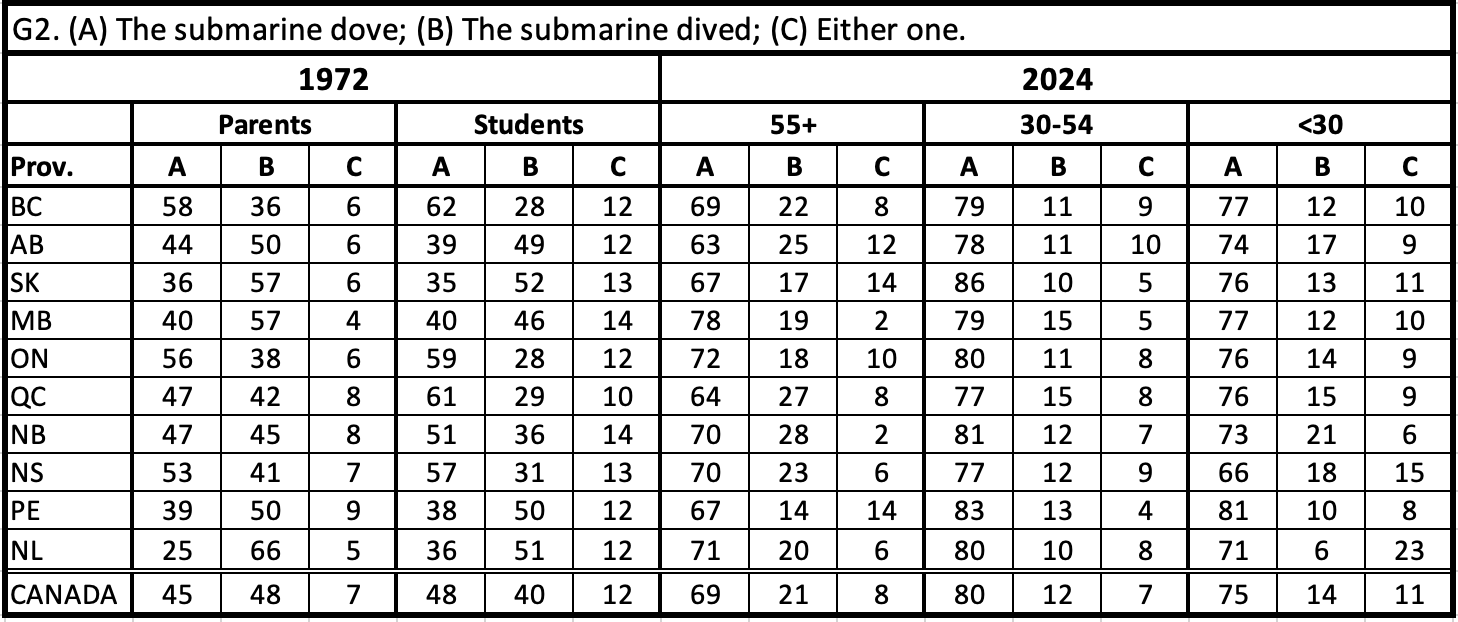

G2. Dove vs Dived

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 72, Q12)

G3. I vs Me

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 74, Q16)

G4. Who vs Whom

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 74, Q21)

G5. Drank vs Drunk

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 77, Q28)

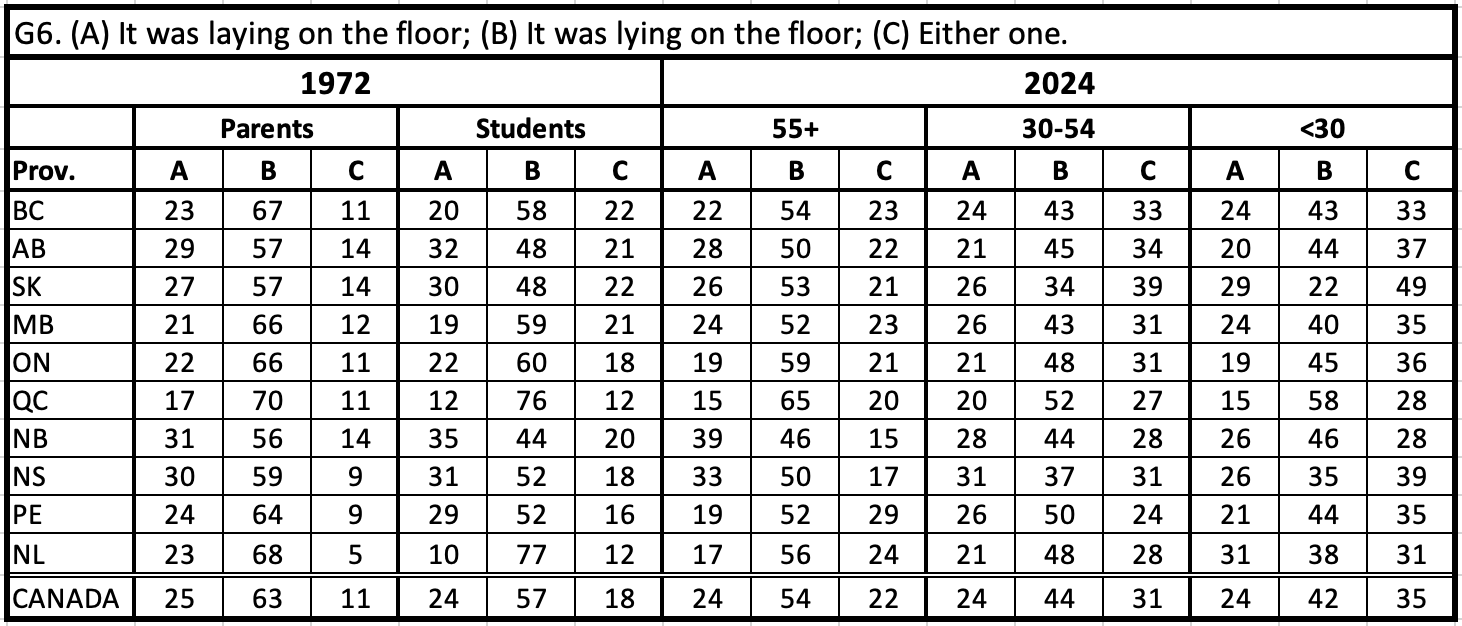

G6. Laying vs Lying

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 78, Q36)

G7. 'As if' vs Like

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 80, Q46)

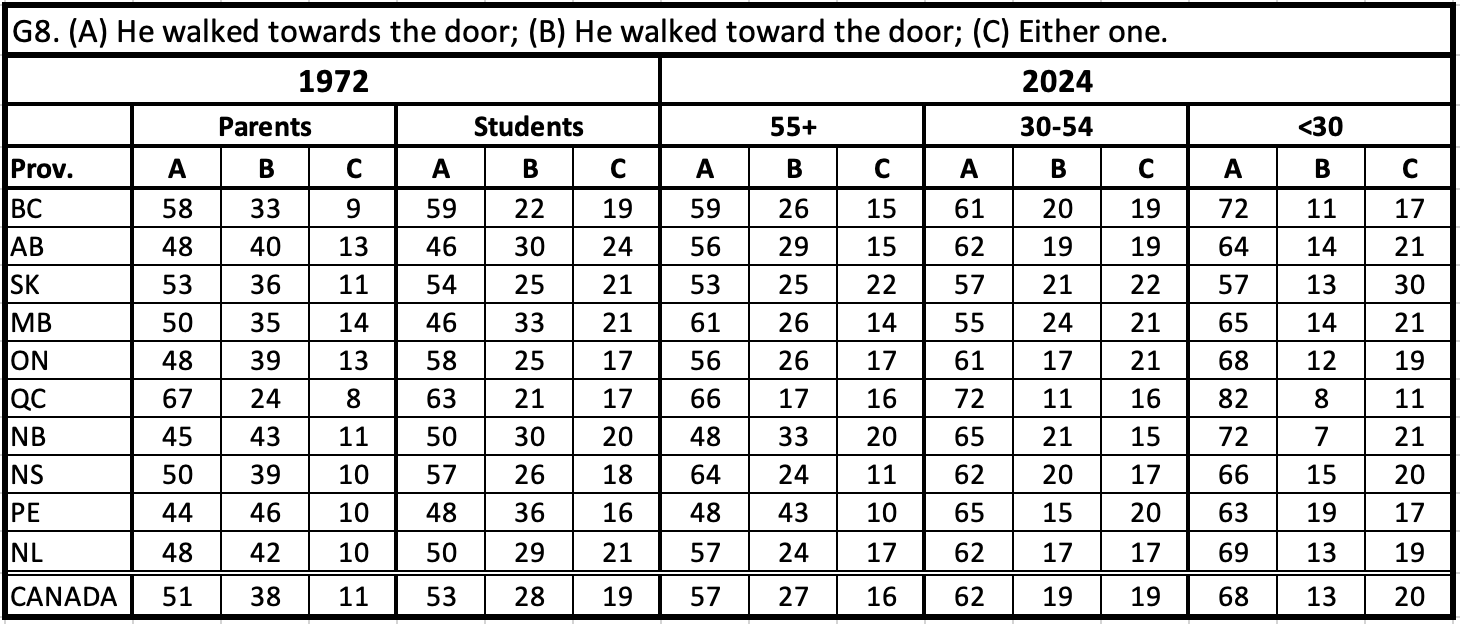

G8. Towards vs Toward

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 80, Q63)

G9. Was vs Were

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 81, Q69)

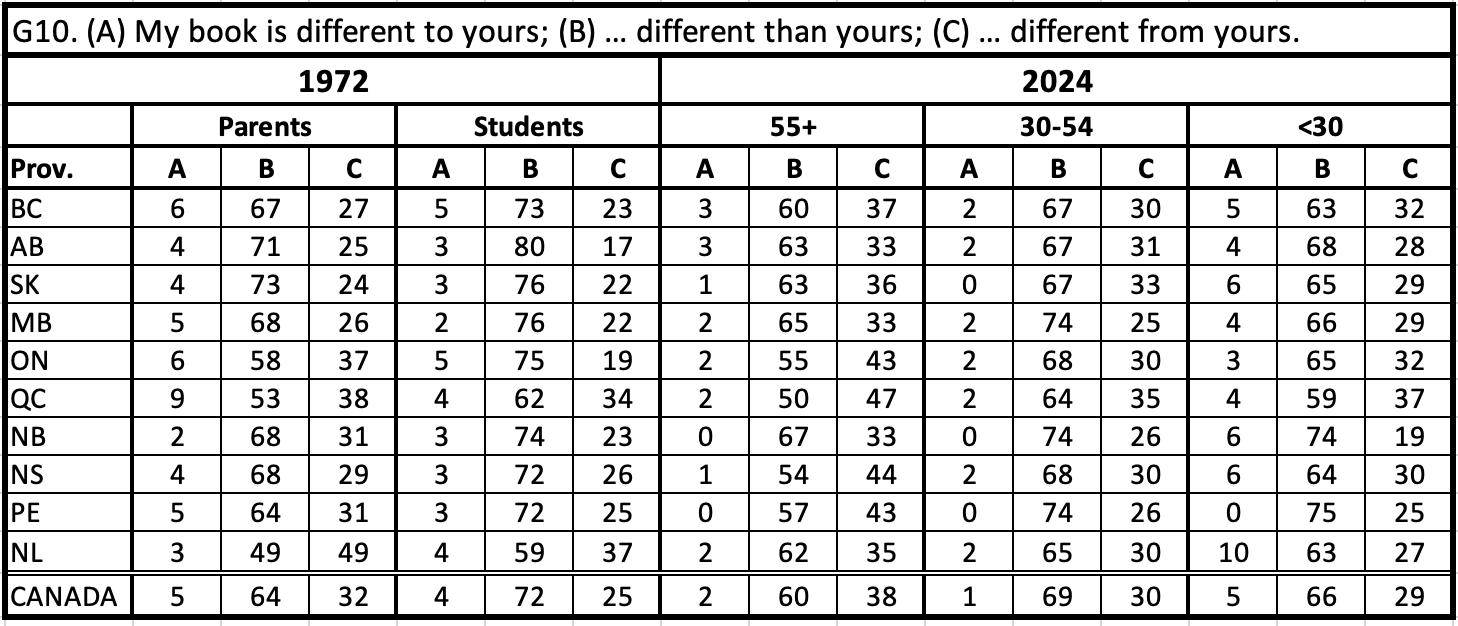

G10. To vs Than vs From

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 82, Q70)

G11. Snuck vs Sneaked

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 83, Q89)

Note: The greyed out cell is an estimate

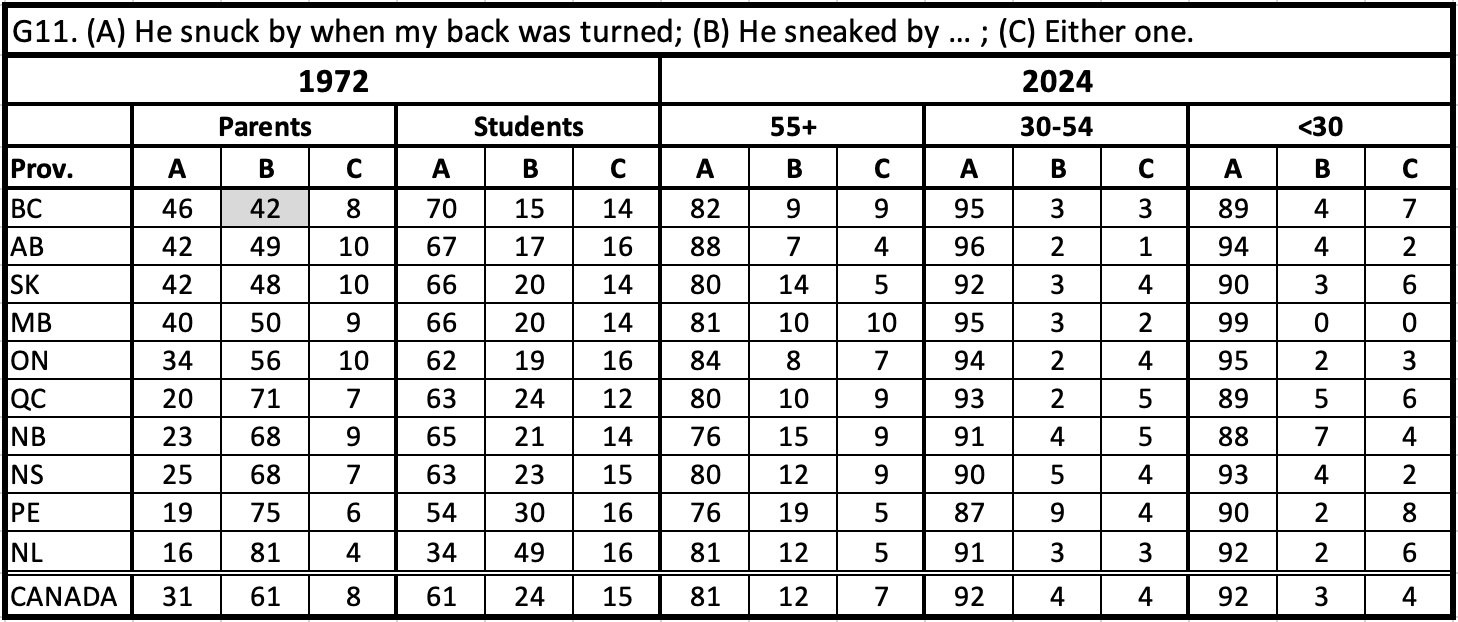

G12. Lend vs Loan

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 96, Q84)

Vocabulary Questions

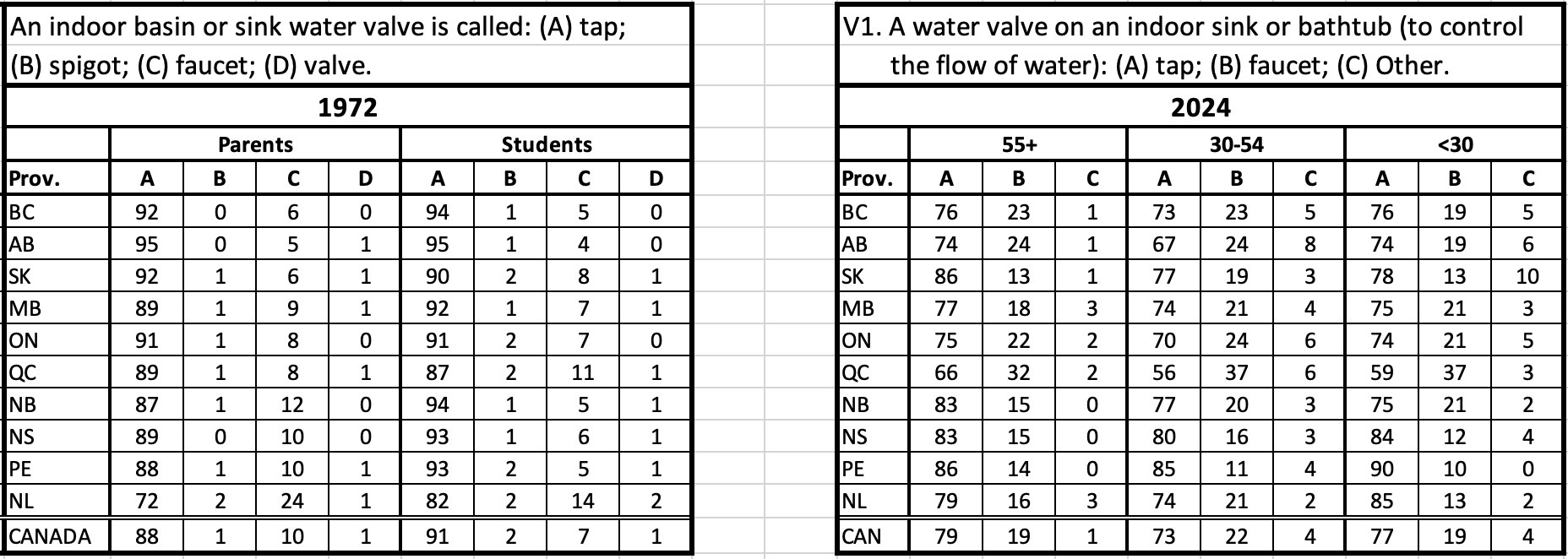

V1. Indoor basin or sink water valve

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 87, Q31)

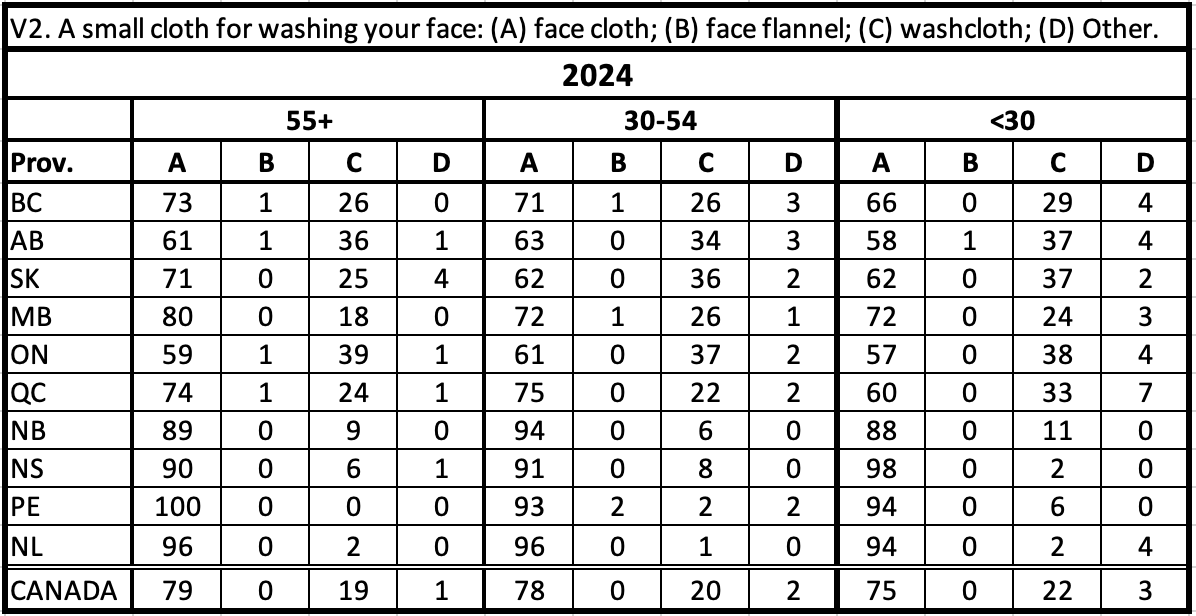

V2. Small cloth

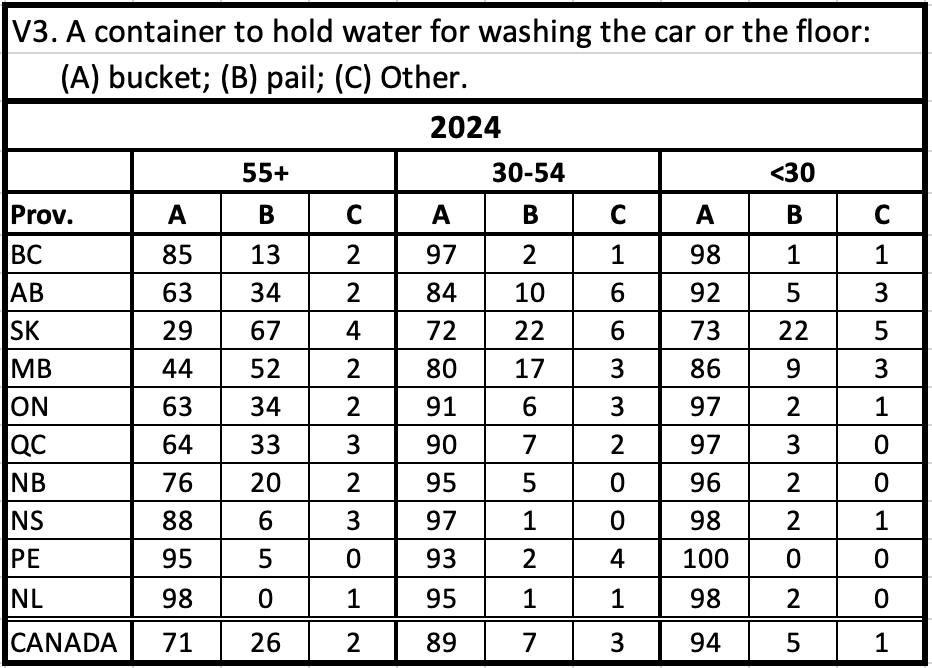

V3. Container to hold water

V4. Devices on roof to catch rain

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 99, Q108)

V5. Upholstered piece of furniture

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 86, Q29)

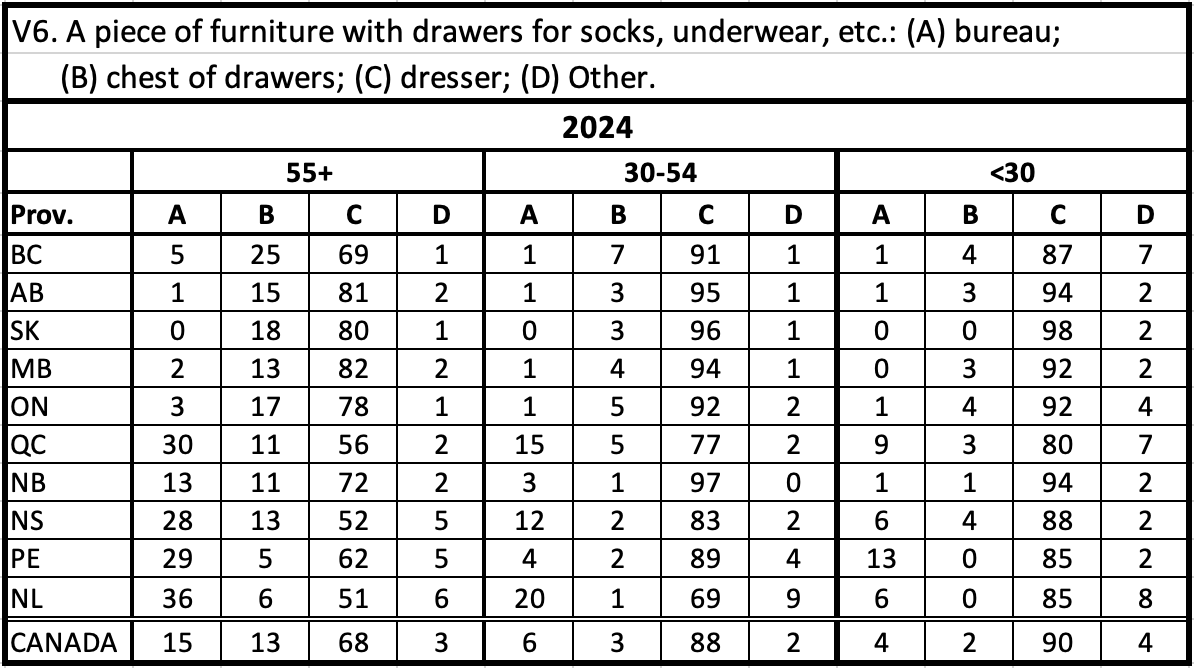

V6. Furniture with drawers

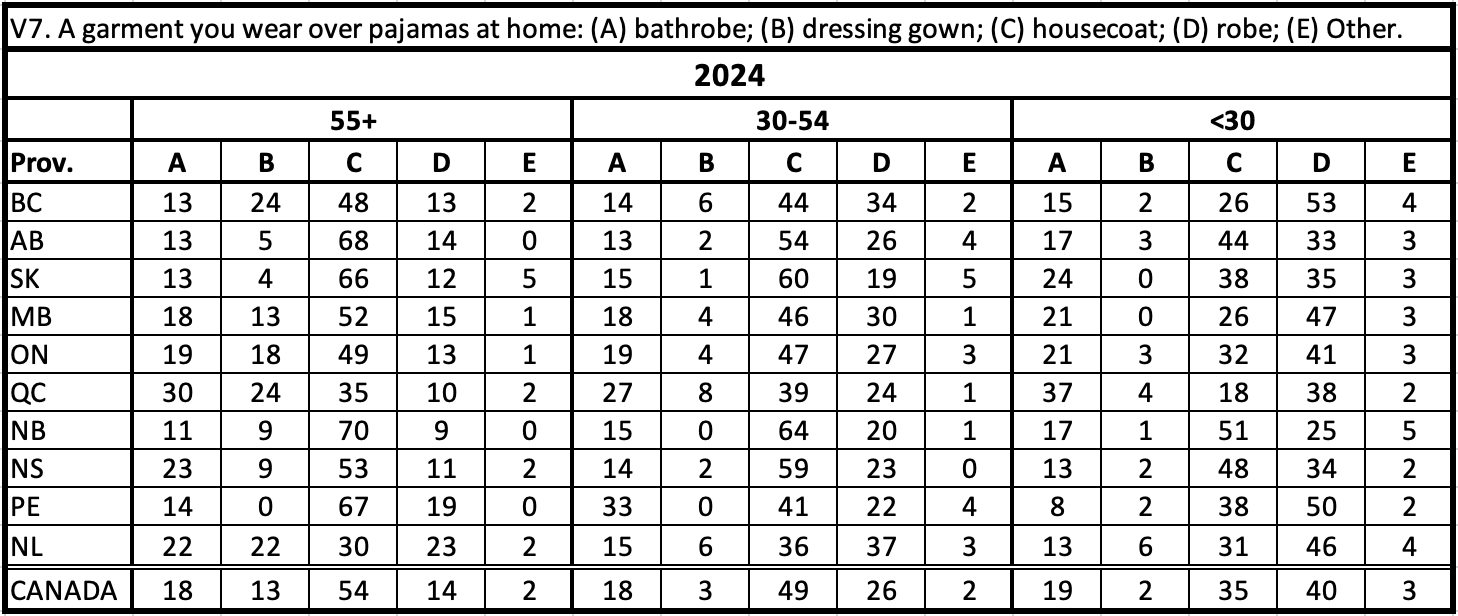

V7. A garment you wear over pajamas

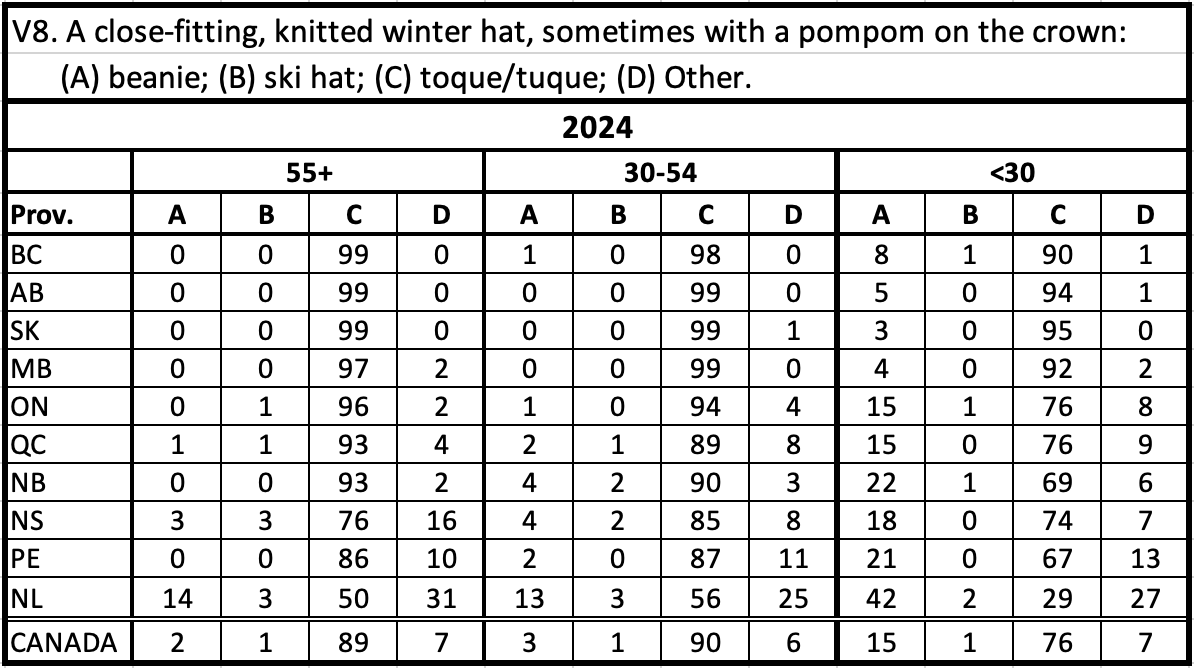

V8. Knitted winter hat

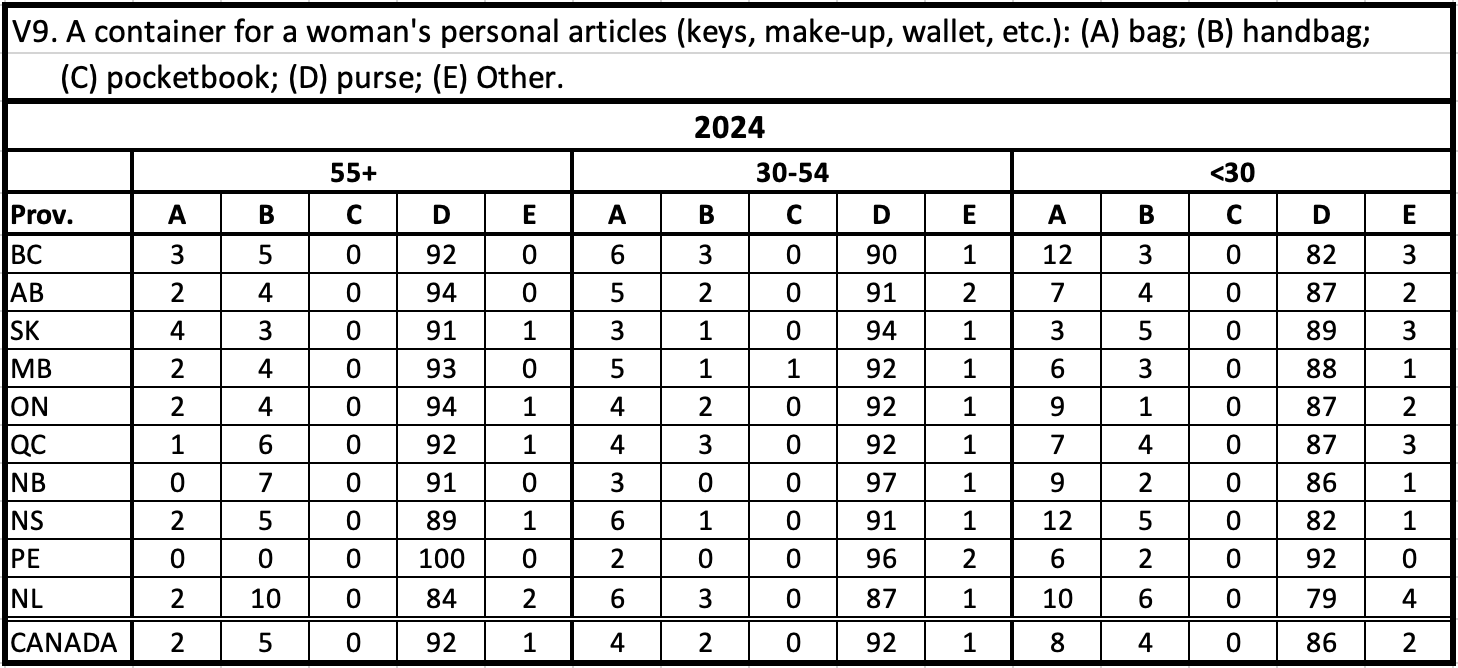

V9. Container for personal articles

V10. Casual athletic shoes

V11. Small house in the countryside

Note: Nova Scotia "other" is mostly bungalow

V12. Small apartment

Note: Newfoundland "other" is mostly bed sitter/bed sitting

V13. Small square of paper

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 90, Q58)

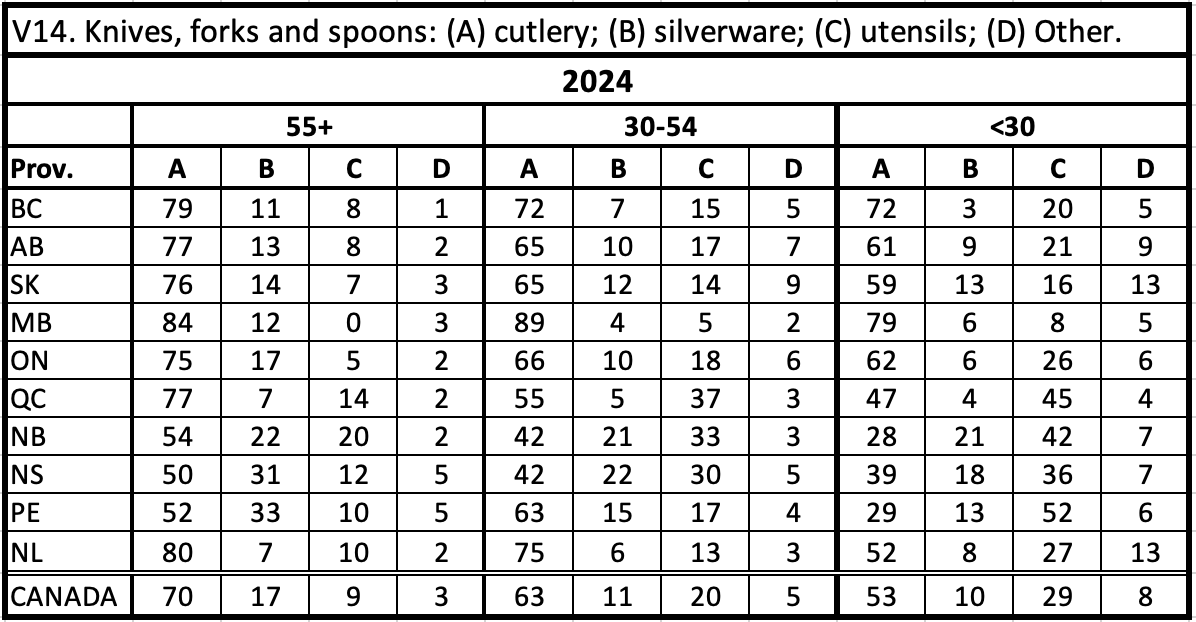

V14. Knives, forks, and spoons

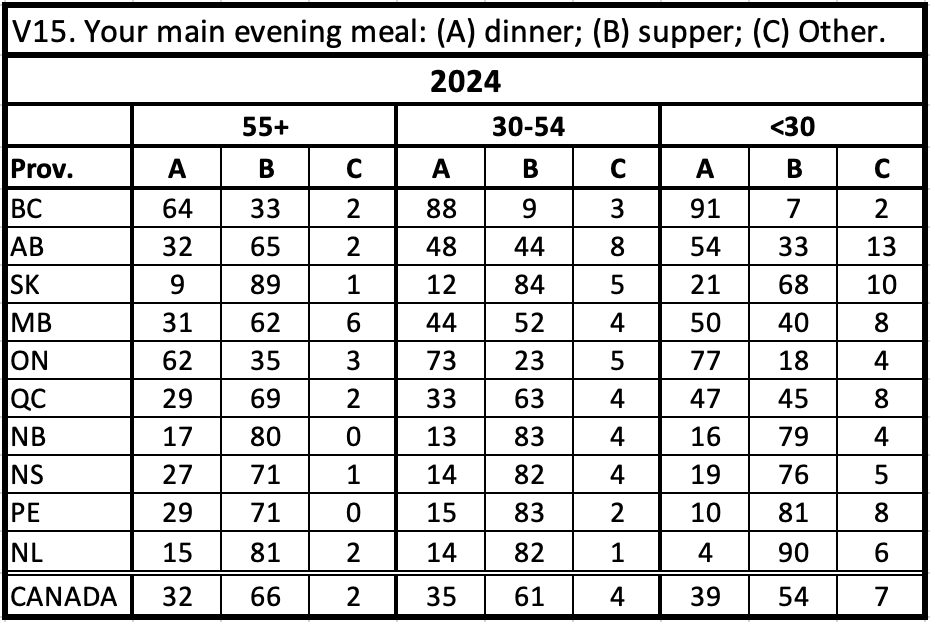

V15. Main evening meal

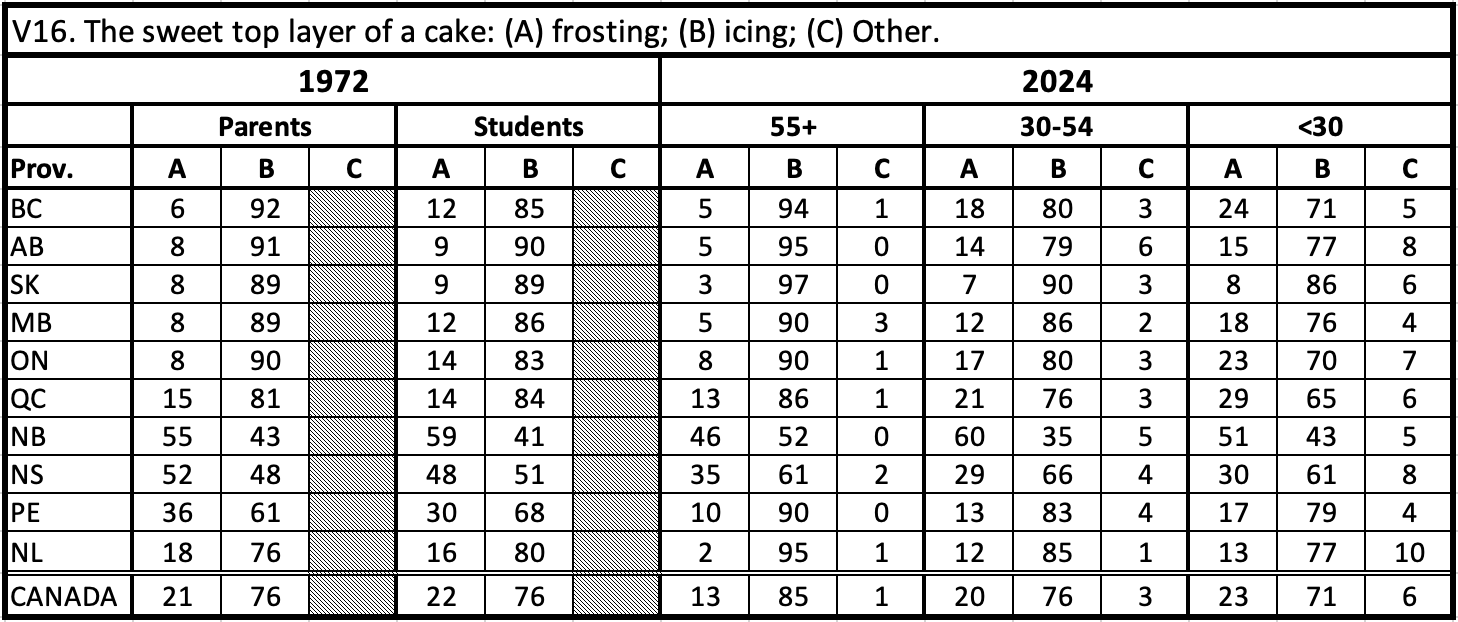

V16. Sweet top layer of a cake

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 88, Q34)

Note: In Scargill & Warkentyne the question is "The sweet hard cake covering is called: (A) frosting; (B) icing."

V17. Carbonated, non-alcoholic beverage

V18. Pizza with all the usual toppings

V19. A year of school before kindergarten

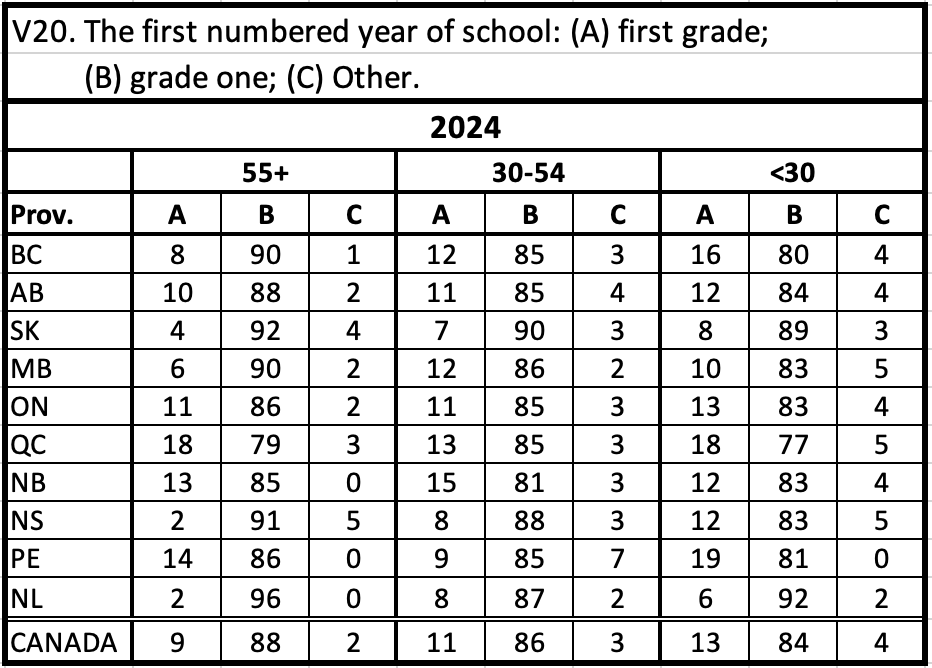

V20. First numbered year of school

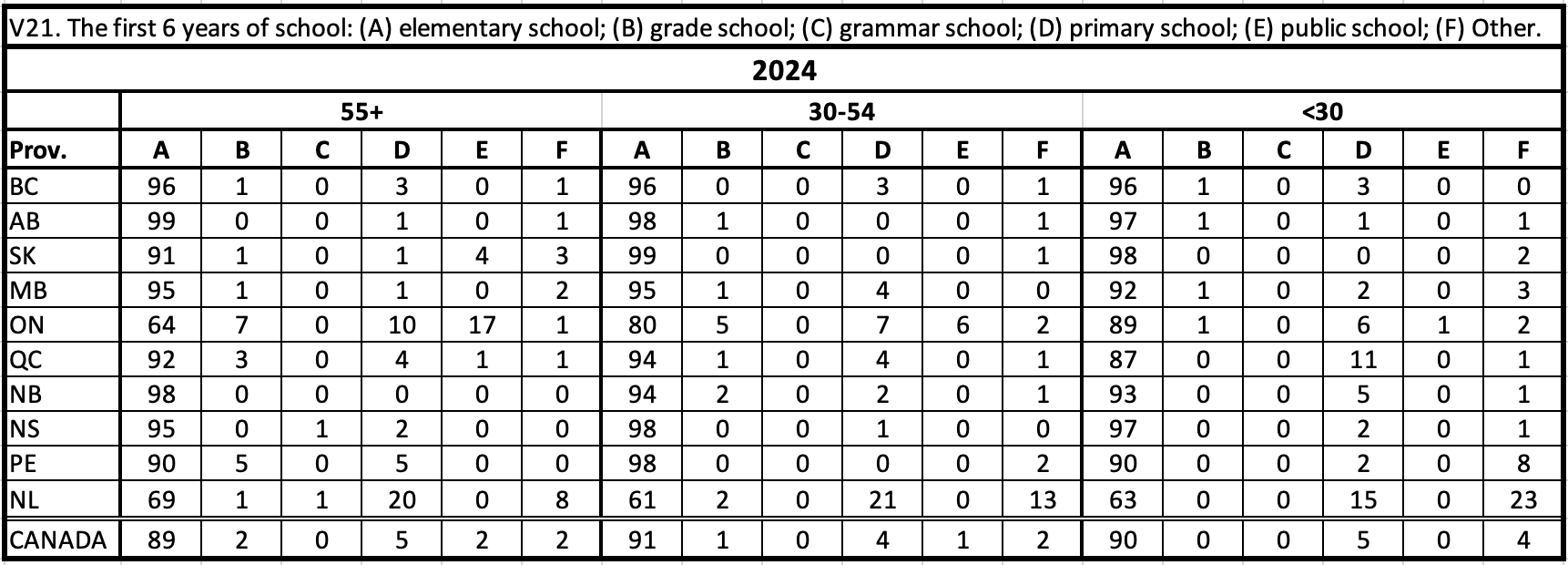

V21. First 6 years of school

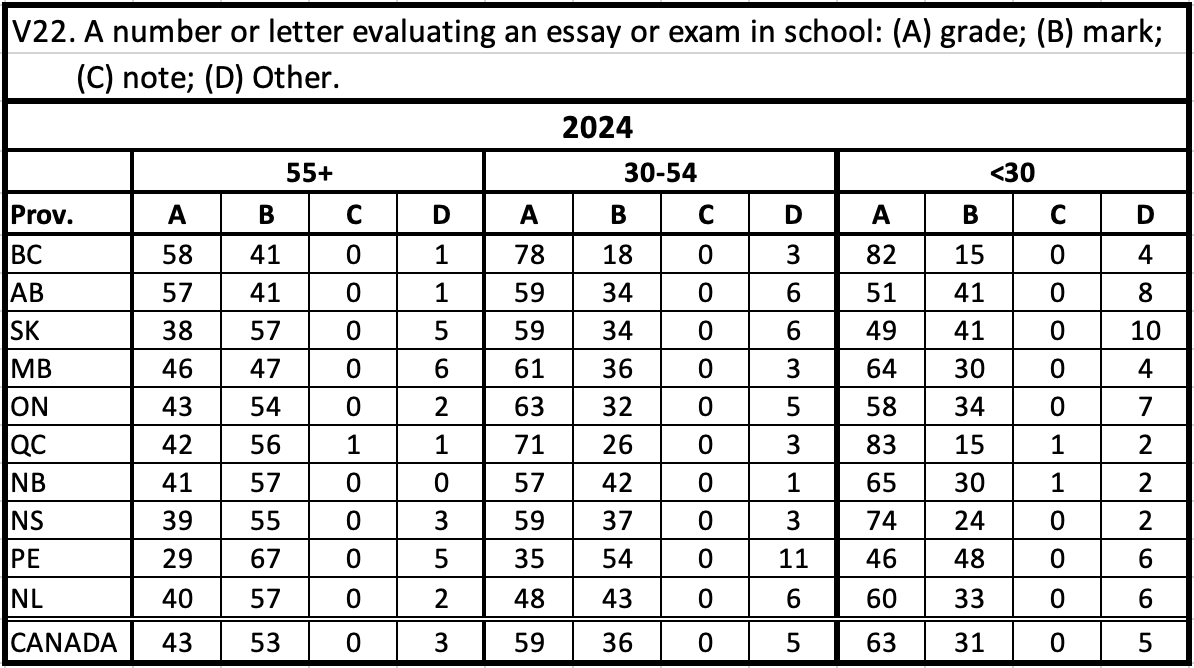

V22. Number or letter of evaluation

V23. Book of lined paper

V24. Pencils used for drawing in colour

V25. Article with shoulder straps

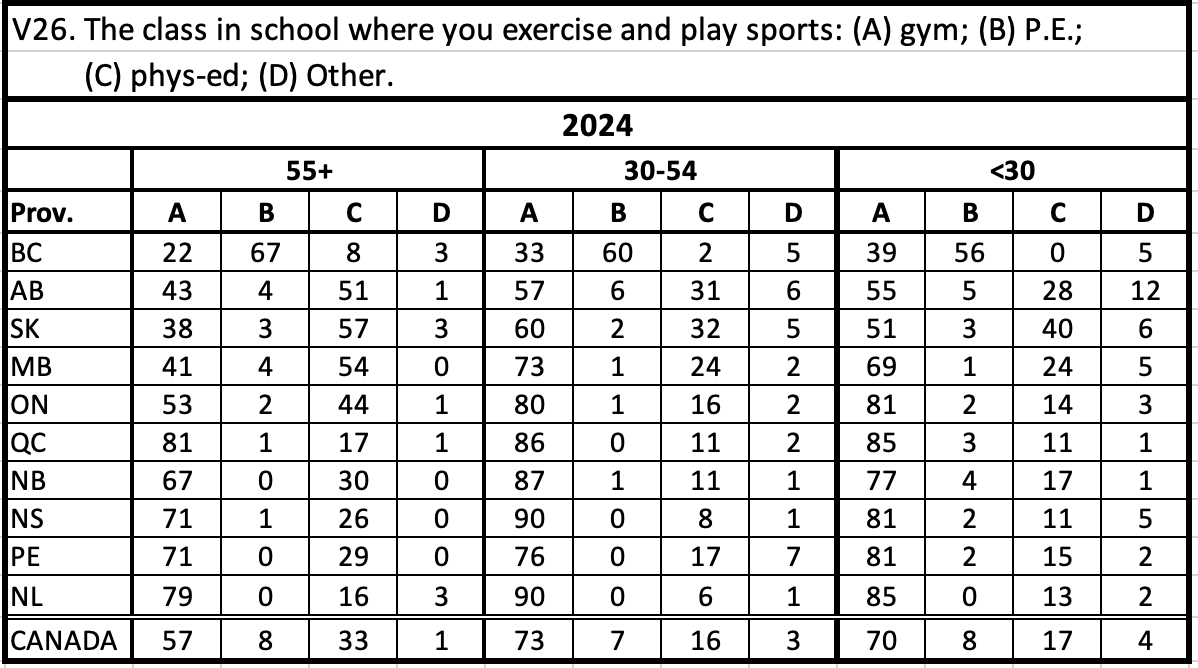

V26. Class in school where one exercises

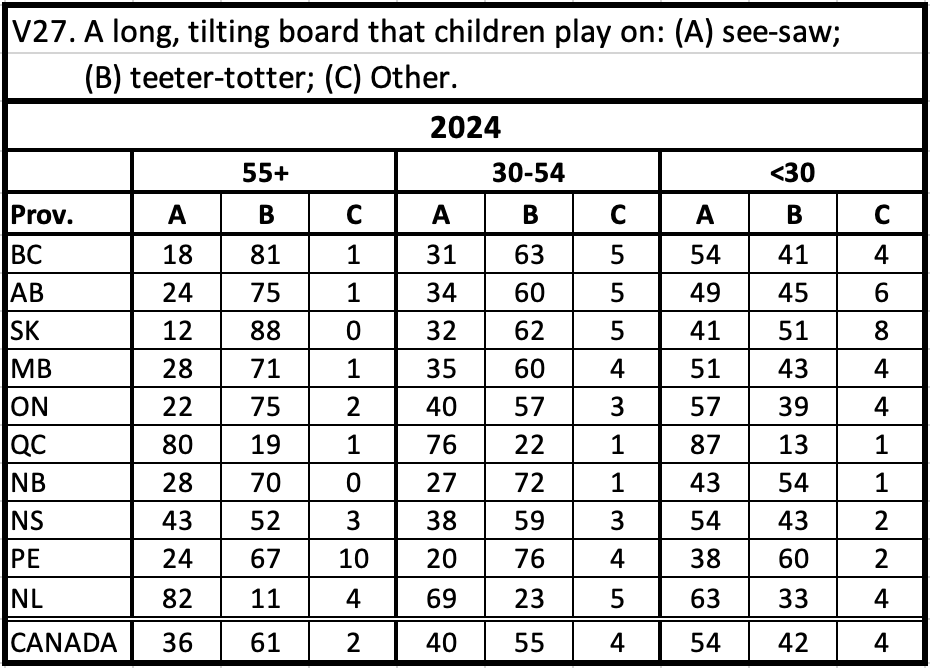

V27. Long, tilting board that children play on

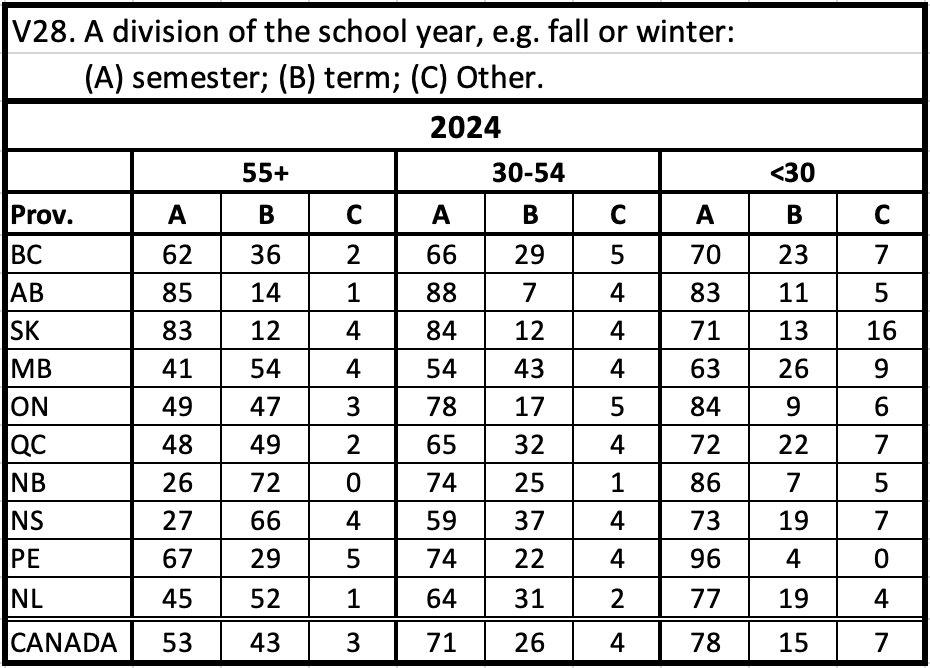

V28. Division of the school year

V29. Summertime break

V30. Small store

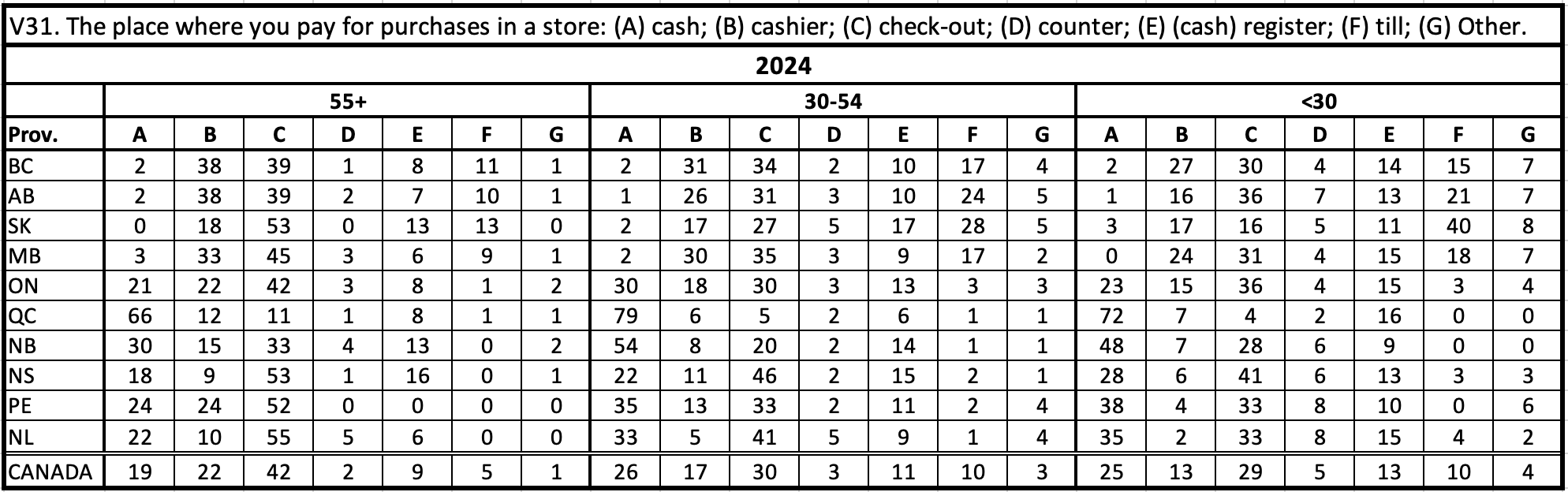

V31. Place where you pay for things

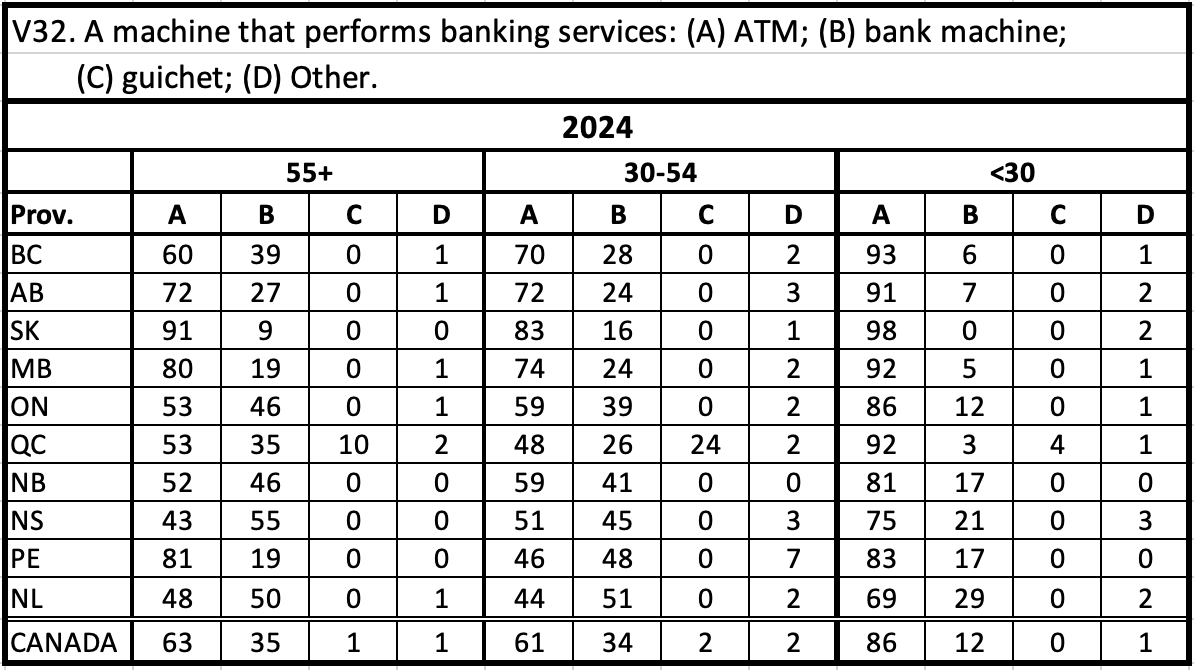

V32. A machine that performs banking services

V33. Multi-level structure for parking

V34. Bright orange objects for traffic

V35. Public toilets

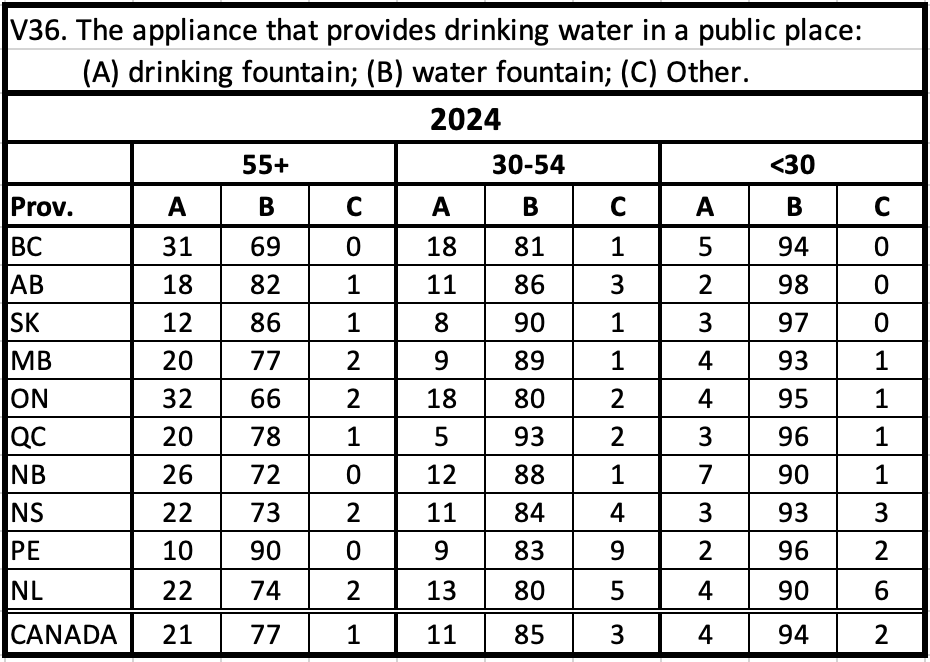

V36. Appliance that provides drinking water

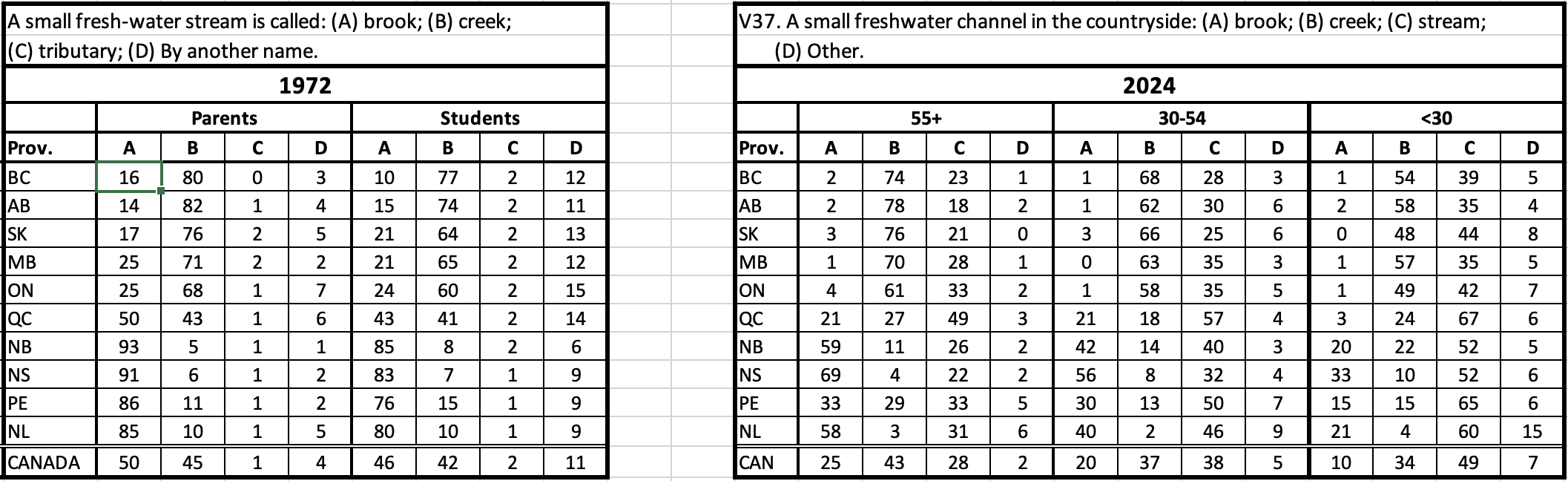

V37. Small freshwater channel

Spelling Questions

S1. Color vs Colour

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 101, Q10)

S2. Center vs Centre

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 101, Q11)

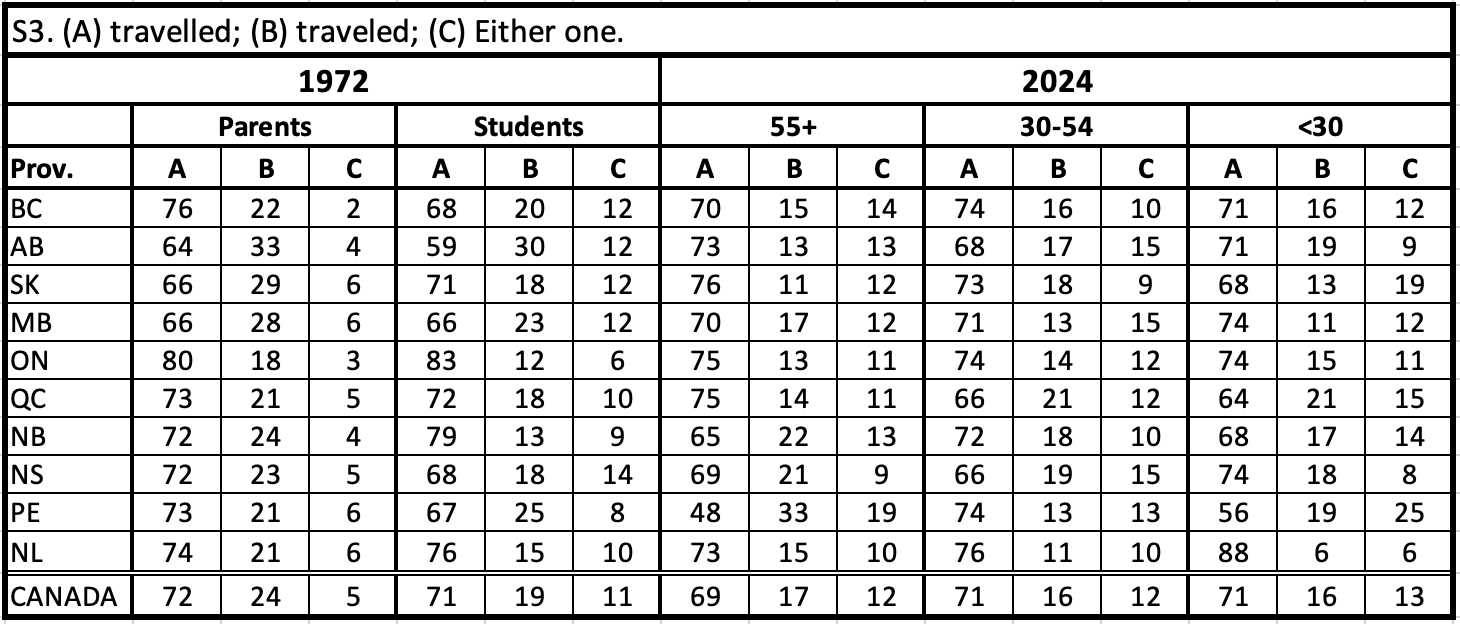

S3. Travelled vs Traveled

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 102, Q18)

S4. Defense vs Defence

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 102, Q57)

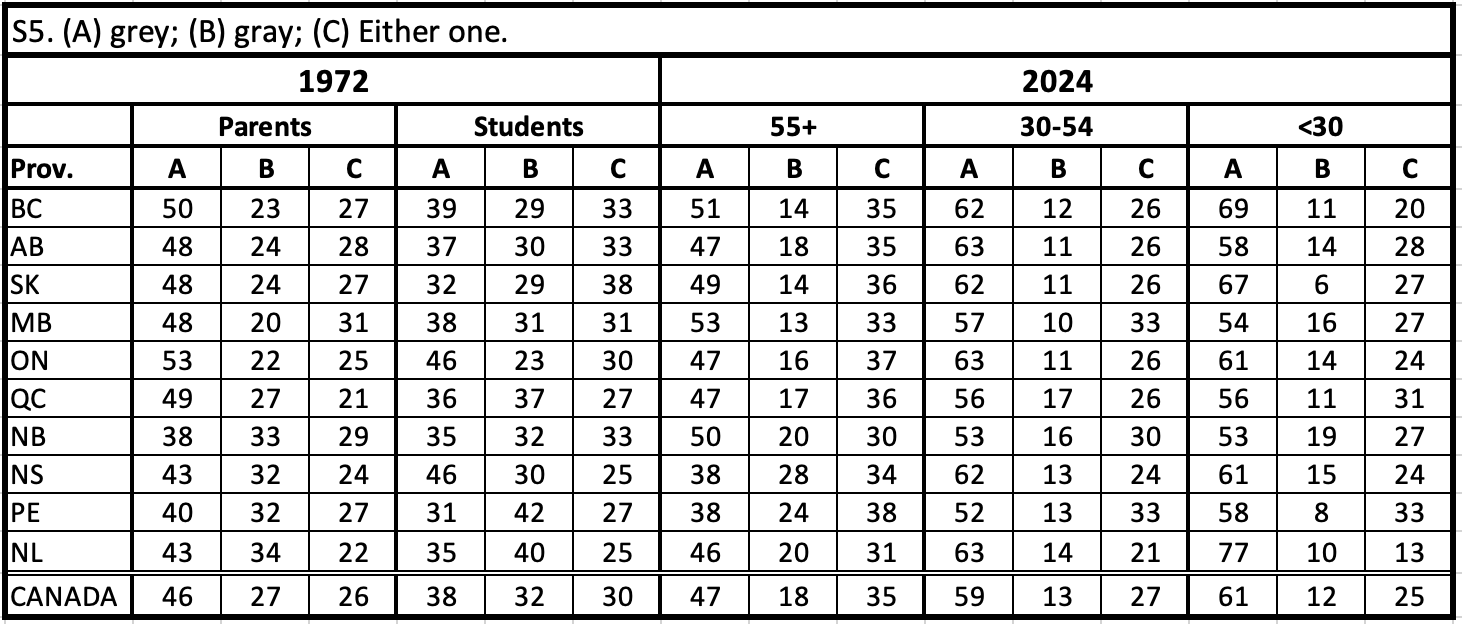

S5. Grey vs Gray

Scargill & Warkentyne (1972: 103, Q64)

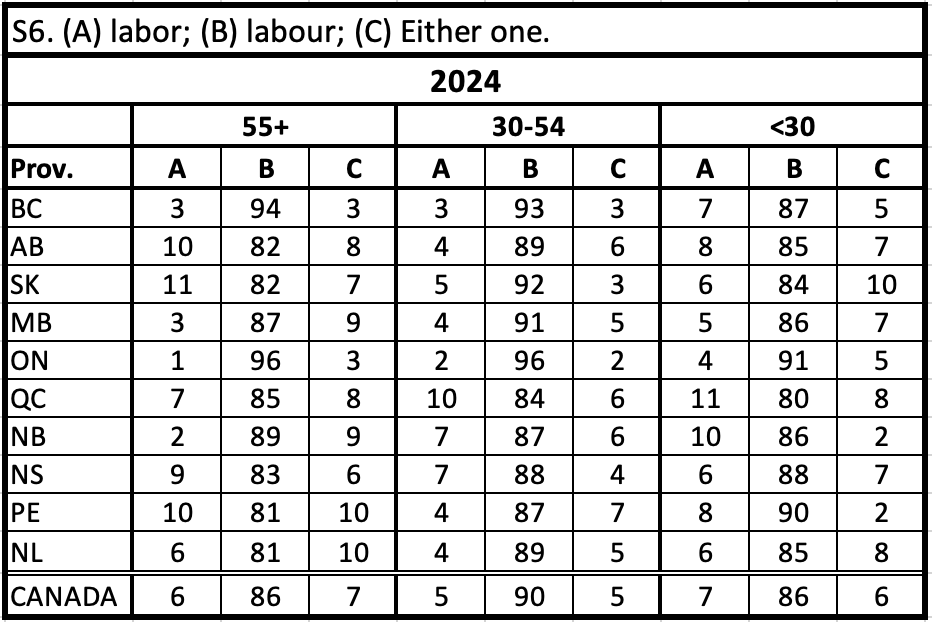

S6. Labor vs Labour

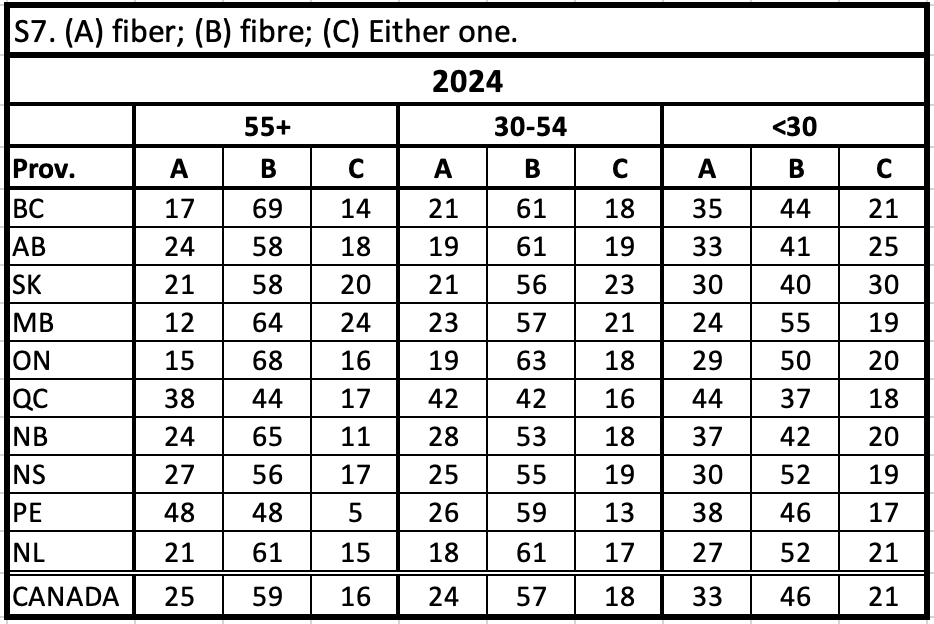

S7. Fiber vs Fibre

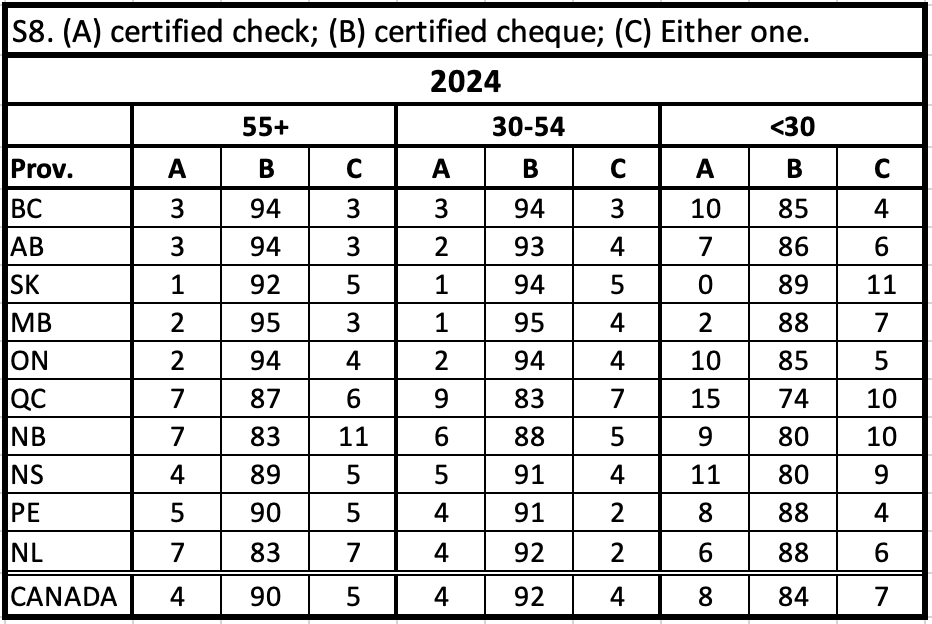

S8. Check vs Cheque

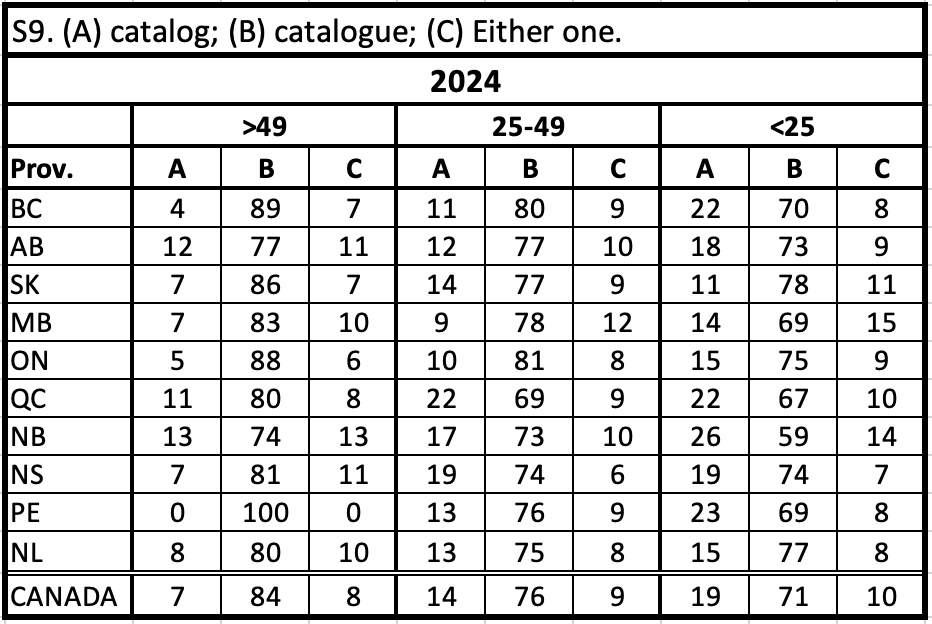

S9. Catalog vs Catalogue

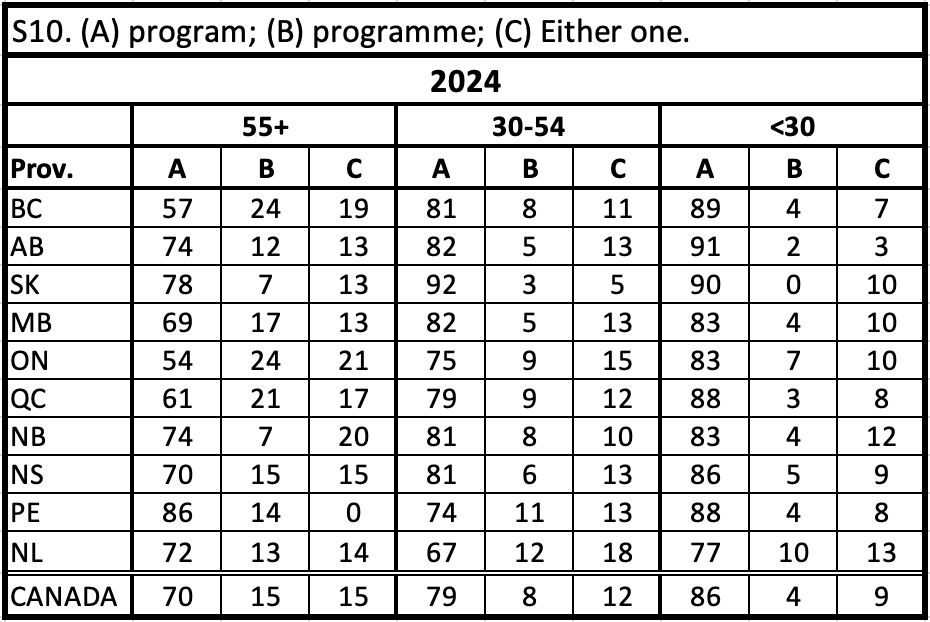

S10. Program vs Programme