Every five years the Bank of Canada and the Government of Canada renew their agreement concerning the Bank’s monetary policy framework. The next renewal will be announced towards the end of this year. The current inflation targeting (IT) framework has been in place since 1991, and has been renewed regularly with only minor modifications ever since.

It’s time for more than cosmetic changes. Defining the target in terms of a level (the price level or the level of nominal income) could convey considerable advantages. The main one would be the introduction of a framework that would mandate the Bank of Canada to correct its past failures to hit its target.

The current target, a 2 percent rate of inflation, is the year-over-year rate of change of the level of prices, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI). Targeting the level instead would specify a target in terms of the CPI itself (either a constant level or one that changes gradually over time in a predetermined way). This would be price-level targeting (PLT), which is discussed in more detail below.

Correcting Past Mistakes

Under the current IT framework, bygones are bygones. If inflation undershoots (or overshoots) the 2 percent target, even persistently, the Bank of Canada doesn’t try to make up for those errors by doing the reverse in the near future. It simply aims to get inflation back to target within its usual horizon of six to eight quarters. (And the Bank doesn’t aim for an immediate return to target because it knows that its monetary policy acts only with a lag of several quarters.)

Under an alternative framework such as price-level targeting, the Bank would correct past deviations from target. What this would look like is illustrated in the figure below. The vertical scale measures the CPI (using the log of the price level so that a constant rate of growth becomes a straight line). The CPI is normalized to 100 in year 1 (4.61 in logs) and grows at an annual rate of 2 percent in the absence of unexpected events, what economists usually call “shocks.” This is represented by the straight line extending to year 10.

Now, suppose that a shock in year 6 pushes inflation up to 3 percent. The red line illustrates the central bank’s response under inflation targeting . Restrictive monetary policy then reduces inflation to 2.5 percent in year 7 and then it returns to the target rate of 2 percent by the end of year 8. The initial increase in inflation is not offset, and in fact since inflation only gradually falls back to target the gap between the initial price level path and the red line actually grows slightly in year 7. So, under inflation targeting, the shock has led the price level to end up on a permanently higher path, even though its rate of growth—the inflation rate—returns to the target 2 percent.

The yellow line illustrates the response if the central bank was instead following a policy of price-level targeting. In year 7, restrictive monetary policy pushes inflation down to 1.5 percent, and by year 8 the price level is back to its original path. The initial period with inflation above the 2-percent target is “compensated” by a few years of having inflation below the 2-percent target.

If inflation deviates persistently from the target, inflation can also deviate on average from the target under IT. Remarkably, this was not a problem during the early years of the inflation-targeting regime in Canada. After the introduction of inflation targeting in 1991, the target was gradually adjusted downward to 2 percent by the end of 1995. Between February 1996 and February 2008 inflation averaged 2.04 percent, almost exactly equal to the target. Inflation did fluctuate, but positive misses almost exactly compensated for negative misses. Also, inflation was quite stable, going outside the Bank of Canada’s 1-3 percent target range only rarely over this period.

Credible Commitments?

Then came 2008, the onset of the global financial crisis and the Great Recession. Inflation fell sharply across the industrialized economies, and many central banks have had difficulty since then getting inflation back up to target. Canada’s inflation rate averaged only 1.53 percent from February 2012 to February 2021, revealing a potential shortcoming of the current IT framework.

Macroeconomic theory teaches us that a central bank can achieve superior outcomes if it can announce its future policies and pre-commit to carrying them out. In the current context, with inflation having undershot the target for a considerable period of time (at least until March of this year), the optimal policy is for the Bank of Canada to commit to allowing inflation to stay above the target for some time in order to offset this undershooting.

Why would it be desirable to have inflation above the target today? If the Bank can credibly make such a commitment, individuals and businesses will expect higher inflation. This will by itself lower real interest rates, encourage higher spending on interest-sensitive goods (investment goods and consumer durables), and help to drive economic recovery, which will in turn put upward pressure on inflation. The way commitment affects expectations makes monetary policy more potent and helps the central bank achieve its target.

The problem with this kind of commitment by the Bank is that it’s subject to what economists call “time inconsistency.” Let’s say the central bank’s announced policy has had its desired effect on expectations and inflation has risen above the target. Because higher inflation has economic costs—which is, after all, why central banks target a low rate of inflation rather than a high rate—it will be in everyone’s interest for the central bank to renege on its promise to let higher inflation persist for a while.

A classic example of the time inconsistency problem in a very different setting is final exams in university classes. Many claim that the main reason final exams are planned and scheduled is to ensure that students actually spend the time and effort necessary to learn the material. Assuming they do this, however, it would then be in the best interest of both the students and the teacher to cancel the final exam on exam day: the students now know the material and generally find exams stressful, and the time spent by the teacher setting the questions and grading the exams could be more profitably spent improving and updating the course materials. Of course this trick would only work once. The following year, students will expect the final exam to be cancelled and their incentive to work hard will be seriously impaired. The commitment to giving a final exam is not credible. This helps explain why many universities impose rules concerning the evaluation of students: it’s a way of making the commitment to give exams credible.

Returning to the topic of monetary policy, we’re now faced with a catch-22. Intelligent consumers and firms can figure out that the central bank will have a strong incentive to renege on its announced policy of raising inflation above the target. The bank’s pre-commitment is not credible and will not have the desired salutary effect on expectations. This is precisely why level targets can generate superior economic outcomes. They substitute for promises by the central bank that everyone knows it will not be able to keep.

Income or Prices?

For any central bank choosing to target levels rather than rates of growth, there are two main choices for which level to target. The main contenders are price-level targeting (PLT) and nominal-GDP-level targeting (NGDPLT).

PLT specifies a time path for the price level (most likely the CPI) and the central bank undertakes to return the CPI to its target path over a horizon of a few quarters. The path could allow for a gradual increase in prices over time, for example at 2 percent per year. NGDPLT specifies a path for nominal GDP, which is equal to real GDP times an index of the average price of what is produced in the economy. It follows that the growth rate of nominal GDP is equal to the sum of real GDP growth and the inflation rate for domestically produced goods and services. If the average rate of growth of real GDP is relatively predictable, a growth path for nominal GDP could be chosen to generate a desired average inflation rate such as 2 percent.

Between these two options, NGDPLT has a number of definite advantages.

Better Performance with Supply Shocks

The main advantage of NGDPLT is its superior performance in response to aggregate supply shocks. To see why, we need to illustrate the fundamental difference between demand shocks and supply shocks, and we begin by assuming that our central bank is using either IT or PLT.

Under either an IT or PLT regime, the central bank will increase (or decrease) its policy interest rate in response to an increase (or decrease) in the rate of inflation, irrespective of the reason for that inflationary change. If the underlying cause of the change is a shock to aggregate demand, output and inflation tend to move in the same direction, and an active monetary policy can improve economic welfare. There is no trade-off between stabilizing output and stabilizing inflation.

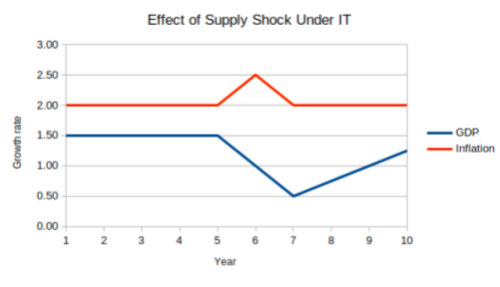

But an aggregate supply shock moves output and prices in opposite directions. Imagine a temporary increase in costs which pushes up prices and reduces output below its full-employment level. This type of hypothetical scenario is illustrated in the figure below. Initially, nominal GDP is growing smoothly at a rate of 3.5 percent, split between real GDP growth of 1.5 percent and annual inflation of 2 percent. The temporary supply shock hits the economy in year 6. Inflation increases to 2.5 percent while real growth falls to 1 percent, so that output is now below its full-employment level.

Under either IT or PLT, the central bank would tighten monetary policy to bring inflation back down to target. Let’s assume they can do this within a single year, so that inflation falls back to the 2 percent target in year 7. Tighter monetary policy works by reducing the demand for goods and services, which would have a negative effect on real growth. This is illustrated by a drop in real growth in year 7 to 0.5 percent, which means that real output is pushed even further below its full-employment level.

The scenario assumes that inflation can be kept at 2 percent from year 7 onwards. Real GDP growth will also return gradually to its long-run value of 1.5 percent as nominal wages and other input prices adjust because of the excess capacity in the economy. How quickly this will occur will depend on the speed of adjustment of wages and other costs due to the economy’s excess capacity. The path in the figure is illustrative only, but it is clear that fighting inflation in response to a temporary supply shock is costly in terms of lost output.

If the central bank recognizes that the increase in inflation is due to a temporary supply shock, it would be better for it not to tighten monetary policy, so as to avoid accentuating the drop in real GDP growth. However, it is often difficult to recognize the exact source of economic shocks in real time. For this reason, IT and PLT are subject to what some economists term a knowledge problem after Nobel prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek. The pieces of information necessary to identify the exact source of an economic shock are too dispersed among markets and individuals for central banks to use this information to identify shocks.

NGDPLT is not subject to the same type of knowledge problem. The central bank needs to focus on just one variable, nominal GDP, the current value of which can be known quite precisely with modern nowcasting techniques. To return to the scenario illustrated in the figure, because a supply shock leads real GDP growth and inflation to move in opposite directions, the combined effect on nominal GDP would be very small and the central bank would therefore not be prompted to engage in an aggressive tightening of monetary policy.

The upshot is that, for an economy subject to either positive or negative shocks to aggregate supply, NGDPLT offers more stability of real GDP growth than a conventional IT policy. More stable real GDP likely means more stable employment. This stability is its main advantage. But there are others.

Other Advantages with Targeting Nominal GDP

Providing Stimulus in Extreme Situations: During the Great Recession, central banks’ policy interest rates remained stuck at their lower bound, and they are now back at their lower bound because of the pandemic. NGDPLT makes it easier to provide stimulus in such situations. With interest rates at the lower bound, if people expect that nominal growth will eventually catch up to its target path, this will stimulate spending. NGDPLT is agnostic concerning which policy tools should be used to achieve the target. With policy interest rates at their lower bound, central banks can switch to Quantitative Easing (the large-scale purchase of government bonds or other financial assets) in order to affect both current growth and expectations of growth in the future.

Reduced Likelihood of Recessions: Recessions are associated by definition with falls in real output. In practice, they have also been associated with falls in nominal output. Avoiding these falls by the use of NGDPLT could reduce the likelihood of the economy falling into recession.

Greater Accountability for Central Banks: NGDPLT would facilitate the accountability of the central bank to the government and to the public. All central banks that target inflation are flexible inflation targeters. They recognize that returning inflation to target takes time, and for that reason they also realize that they can also stabilize fluctuations in real output in the short run. Macroeconomic theory shows that central banks face a trade-off between the variability or volatility of real GDP and the volatility of inflation. Evaluating the performance of IT involves measuring the volatility of both inflation and real GDP, and assigning weights to each measure based on theoretical models. An inflation-targeting central bank would get a good grade if this weighted measure was at or close to the best achievable trade-off under the optimal policy, which can only be calculated using a structural model of the economy. Focusing on a single target makes accountability much easier and less reliant on economic theories.

Enhanced Financial Stability: NGDPLT would lead to greater financial stability. Most debt contracts stipulate payments in nominal terms (i.e. unadjusted for inflation). Recessions typically mean that individuals’ nominal incomes drop substantially, raising the burden of carrying their debt and leading to more defaults and bankruptcies, potentially threatening the stability of the financial system. Stabilizing nominal incomes would mitigate this effect. Also, if nominal GDP follows a stable growth path, then if real growth decreases (as it does in recessions), inflation will increase. This means that inflation will be countercyclical in an NGPDLT framework. In recessions, inflation would be higher than under IT or PLT, and this would erode the real value of debt burdens more than during booms. This would also help reduce the frequency of defaults and bankruptcies in downturns.

Conclusions

The Bank of Canada’s adoption of inflation targeting in 1991 was largely a leap of faith. No one knew exactly how it would work or how well, only that the previous framework of monetary gradualism had broken down. The theoretical backing for IT came only later. By contrast, there are strong theoretical arguments in favour of level targeting in general, and nominal-GDP-level targeting in particular.

Inertia will continue to be the main force preventing central banks from making major changes in their monetary policy frameworks. Inflation targeting has not been a perfect regime but it performed reasonably well until the Great Recession. It’s not completely broken now—but it is cracked, and may be partly responsible for the sluggish recovery of our economies from the Great Recession. The pandemic crisis and the path to recovery present an opportunity to do more than just tinker with the monetary policy framework. If the Bank of Canada fails to take advantage of this opportunity it may not get another chance before the next major crisis.

About the Author

Professor Steve Ambler has taught at l’École des sciences de la gestion de l’Université du Québec à Montréal (ESG UQAM) since 1985, and has chaired the Department (2012-2015).Ambler has held visiting positions at the Université de Paris I (Panthéon-Sorbonne), the European University Institute, the Institut für Höhere Studien in Vienna, and the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian central bank).He is the author of numerous articles in journals such as the Journal of Monetary Economics, the Review of Economics and Statistics, and the Journal of Money, Credit and Banking.

He is a past president of the Société canadienne de science économique (1998-1999). He has been an Associate Editor of the Canadian Journal of Economics (1992-1995) and of Canadian Public Policy (1998-2003). He was on secondment to the Bank of Canada as Special Adviser from September 2006 to July 2007. He was Secretary-Treasurer of the Canadian Economics Association from 2007 to 2012.