The provision of housing in China is a complex and highly regulated process, and a number of factors must be explained to understand it fully. This chapter, which attempts to do so, is divided into five parts: the first part introduces the housing policies of Hong Kong and Singapore, after which Chinese policies have been modeled; the second part reviews different approaches to urban planning and housing design in China since the Revolution; the third part exposes the many factors involved in the housing process; the fourth part identifies and discusses the main problems in the present housing system; and finally, the fifth part presents the recent housing reforms and their impacts on the system.

2.1. Housing policies in Hong Kong and Singapore

The Republic of Singapore and the British Colony of Hong Kong are the two successful city -states in Asia, in terms of both economic and urban development. They were founded by the British to carry out entrepôt functions and recently emerged as two leading financial centers in Asia (Wang and Yeh, 1987). As the two market economies with the highest rates of economic growth in the last twenty -five years, they are also those with the largest per capita public housing programs (Castells et al., 1990). A brief review of the evolution of public housing policies in Hong Kong and Singapore is presented as an introduction to housing policies in China, which were strongly influenced by those of the two city-states.

a) Housing Policies in Hong Kong

The housing program has been one of the success stories of Hong Kong, and is among the most remarkable achievements world-wide. Almost three million people or half of the population of Hong Kong lives in public housing. Public housing has been a top priority for the government since the post-war period, with over 35,000 units built each year, divided into public rental apartments and home ownership apartments (HKHA, 1987). The development of the housing policy in Hong Kong can be divided, based on the level of government intervention, into three major periods: the resettle ment stage, the restructuring period and the privatization policy (Castells et al. 1990).

The Resettlement Stage (1954-1964)

Before 1953, the attitude of the Hong Kong authorities with regard to the provision of housing was one of laissez faire. Following the disastrous fire which devastated the Shek Kip Mei squatter area in 1953, the government had to implement a large-scale resettlement program to rehouse the affected population. This marked the beginning of direct government intervention in housing in Hong Kong, mainly based on large-scale slum clearance, eviction of squatters, and their rehousing in emergency estates or temporary housing (Keung, 1985).

During the first decade of the implementation of the resettlement program, large-scale, low -standard resettlement blocks were built to accommodate squatters 1. The goal was to produce huge numbers of resettlement units without any consideration as to quality or planning of facilities, and to clear and control as many squatters as possible. The public housing program moved ahead rapidly and, by the end of 1959, it had provided housing for a quarter of a million people (Yeh and Fong, 1984). By 1972, 1.6 million people were living in various types of government-subsidized housing (Yeh and Fong, 1984).

The Restructuring Period (1973-1983)

This period was characterized by the transformation of the ad hoc form of government intervention in housing to a continuous, direct and planned one. In October 1972, Sir Murray MacLehose, the newly appointed Governor, announced a Ten Year Program aimed at providing 1.8 million people with permanent, self-contained homes with amenities 2. It marked the planned physical decentralization of public housing development, upgrading of existing public housing, implementation of the Home-Own ership Scheme, and increased concern for the conditions of tenement slum dwellers in the central city (Castells et al., 1990). Strong emphasis was placed upon the construction of better quality public apartments for rent and for sale, and on general improvement in design and management of public housing estates. Better quality, however, often translated into less quantity.

To manage such an ambitious program, all existing housing agencies were unified in 1973 into a single integrated housing institution with comprehensive functions, the Housing Authority 3. It was given responsibility for policy formulation, while its executive arm, the Housing Department, was entrusted with the translation of policies and goals into specific programs for implementation and the oversight of the planning, construction and management of public housing estates (Yeh and Fong, 1984).

The planning of some very large developments in the once rural parts of the New Territories led to the proposal for the new town program in 1973, wherein public housing, industrial units and com mercial facilities would intermix in a decentralized and relatively self-contained area. Since then, most of the public housing has been built in the new towns. The Home Ownership Scheme (HOS) was introduced in 1976 to give people greater freedom of choice as to whether to buy or to rent their own flat and to enable lower middle income people to acquire homes at a reasonable price (HKHA, 1988). The Home Ownership Scheme is managed by the Housing Authority and financed by the government, which recoups its expenditure from the sale of apartments. Apartments are sold at cost price and below market levels. The eligibility criteria are based on income and household size. Special incentives were introduced to encourage the purchase of dwelling units 4.

The Privatization of Housing Policy (1984 and beyond)

In the early 1980s, the Private Sector Participation Scheme, in which the government invites private developers to produce apartments similar to the Home Ownership Scheme to be sold at a fixed price to lower-income households, was introduced (Castells et al., 1990). Subsidized loans to help public housing tenants and newcomers to the market to buy private apartments were made available. The selling of public housing apartments to their tenants and the use of the Home Ownership Scheme in the redevelopment programs were also encouraged. In 1987, a Long Term Housing Strategy was elaborated, extending the housing policy beyond the end of British sovereignty until 2001. The new policy was dominated by the privatization of public housing, in terms of both supply and demand. One of the main objectives of the Long Term Housing Strategy was to deliberately limit the public subsidy to tenants who had improved their economic situation and were still in the public estates (HKHA, 1988).

Initially, most housing estates had followed a repetitive row layout, but since the mid-1980s housing design has been reoriented toward a variety of high-rise block types within the same estate, arranged around recreational spaces. This not only allowed for a slightly more diverse environment, but also for a variety of sizes of apartments and a better integration of the unique characteristics of each site.

In summary, the emphasis of the Hong Kong public housing program has shifted from one of quantitative emergency relief and squatter-clearance to a more quality-oriented but limited program, then to improved public housing and new town development, and finally to middle-class housing estates, urban redevelopment and privatization of public housing.

b) Housing Policies in Singapore

Singapore is the third most prosperous country in the Asian Pacific Rim, after Japan and Brunei, and has the second busiest port in the world (Castells et al., 1990). Its public housing program has been a critical factor in this prosperity. Singapore operates the largest public housing program among all the urban systems in the capitalist world, with 85% of its population housed in government apartments, 70% of whom have home ownership status5 (Castells et al., 1990). The evolution of the housing policy in Singapore can be divided into three main periods: the First Five-Year Program, the Second Five -Year Program, and the post-1970s period.

The First Five-Year Program (1960-1966)

When the People's Action Party came to power in 1959, the housing shortage and general housing conditions in Singapore were appalling. The highest priority was given to improving the housing situation, and public housing programs were to form an integral part of national development policies. The national housing program was initiated in 1960, and entrusted to the Housing Development Board(HDB), a public authority with comprehensive functions. The HDB was to be responsible for clearing land, redeveloping the urban area, and for the planning, management and production of housing 6 (Castells et al., 1990). It was given great autonomy in implementing policies set by the government.

The HDB immediately initiated the First Five-Year building program to provide shelter for low-income people in the form of basic rental apartments. The strategy was to build as many housing units as cheaply and quickly as possible to solve the housing shortage and to meet the needs of the rapidly increasing population. The qualitative aspects of housing were sacrificed 7. As a result, space standards were low, layouts monotonous, architectural design unimaginative and supporting facilities inadequate. To maximize the use of land, slab apartment buildings were built up to twelve stories, and in the 1960s, point blocks were developed up to a height of twenty-five stories (Hyde, 1989). The worst of the housing problem was resolved after five years.

The Home Ownership Scheme was introduced in 1964 to encourage private ownership and to enable lower income groups to own their units8 (Siew-Eng, 1989). Eligibility was based on four crite ria: citizenship, non-ownership of private property, income, and family formation 9. The allocation of housing units was and still is based on a first-come-first-serve basis. Originally, a registered household had the right to choose both the type of flat and the broadly defined housing zone in which it wished to reside, but not the specific block or floor. Final allocation was by ballot. Today, instead of balloting, applicants are called to select from the available desired flat-type and zone (Hyde, 1989).

The Second Five-Year Program (1966-1970)

The Second Five-Year Program, initiated in 1966, shifted priority from speed and expediency to quality and amenity. New housing estates were better planned, with bigger and less standardized apart ments, more generous allocation of open space and greater emphasis on landscaping. The quality of life in the housing estates was enhanced through the provision of specialized facilities such as sports complexes. In 1968, an innovative housing financing scheme was introduced as part of the Home Ownership Scheme, to convert housing from a public good into a commodity. Citizens eligible to buy public housing were permitted to use a portion of their Central Provident Fund (CPF) savings to pay for the down payment and monthly installment payments on their HDB apartment. By 1970, 35.9% of the population in Singapore was living in public housing, while 9% was living in owner-occupied HDB apartments (Castells et al., 1990).

The 1970s Onwards

In the early 1970s, HDB estates of unprecedented scale were built using the same planning principles as those of the early self-contained HDB estates, and the concept of the "new town" was introduced. High-rise, high-density new towns had larger populations which could support a broader spectrum of services and allowed planners greater flexibility in the planning of community facilities. A few years later, a new planning concept, that of the precinct, was introduced in response to the excessively large neighborhoods of the new towns which hindered social interaction (Hyde, 1989). These precincts were characterized by their emphasis on the human scale of the environment and the concentration of community facilities at a focal point among six to eight blocks characterized such precincts.

In 1971, as an incentive to encourage flat-dwellers to upgrade to larger apartments and to pro mote home-ownership, the HDB allowed homeowners to sell their apartments on the open market after five years10 (Lim, 1983). To prevent speculation, people who sold their unit on the market were not allowed to apply for public housing for two and a half years.

Before 1973, the HDB built exclusively for the low-income group, while private developers saw to the housing requirements of the middle- and high-income groups. But with the escalation in the price of private housing in the early 1970s, the Housing and Urban Development Company (HUDC) had to be set up in 1974 to provide middle-income housing. The HDB eventually absorbed the function of the HUDC and such units became fully integrated within the overall planning and development of HDB estates (Castells et al., 1990). As a result, there was a shift towards bigger and more attractively designed apartments to satisfy the demands of a more affluent group of home-seekers.

In recent years, there has been a major decrease in population growth in Singapore. As a result, too many housing units have been built and the HDB has been unable to sell or lease a significant quantity of its housing stock.

c) Common Traits

Although there are great differences in ideology and political systems between Hong Kong and Singapore, many similarities could be observed in the evolution of their housing programs. Both are characterized by strict and highly organized policies, and are controlled by decentralized housing authorities. A general trend toward the privatization of the housing stock became current, as well as a shift from inner-city development to the construction of self-sufficient new towns at some distance from the city center. All new housing units have been built in the form of large-scale, high-rise, high-density estates, with a recent tendency to integrate prototypes of various height and density to increase diversity.

The main motive for the development of such national strategies for the provision of public housing has been described by a need to stabilize the social, economic and political structures of the former colonies (Keung, 1985) (Siew-Eng, 1989) (Castells et al. 1990). In both city-states, the housing policy has resulted in the stimulation of economic growth, the creation of a stable society and a perpetuation of political legitimacy. Three characteristics common to both city-states have been sug gested as necessary conditions for the development of such public housing programs: political commitment to housing provision and the contribution of substantial public funds; active land policies based on the public ownership of land; and the managerial efficiency and relative autonomy of both public housing authorities (Castells et al., 1990).

A strong political will and financial commitment to universal housing provision are essential to the development of successful housing programs11. It can be argued that the non-democratic govern ments (in the western sense of the word) based on political authoritarianism played an important part. By enforcing strict population control to regulate housing demand and implementing regulations facilitating development, the governments could more easily implement their planned policies (Lima in Angel et al., 1983).

The public ownership of land was also essential for the development of such public housing programs (Kwok in Angel at al., 1983). It puts the government in a relatively strong position to influ ence the project design and densities through lease and planning control. In addition, land sales are a major source of revenue for public expenditure and investment (Kwok in Angel at al., 1983).

The flexible system of decentralized monitoring of the projects and of managing the housing estates, as well as the considerable power and relative financial autonomy of the public housing au thorities, also help to explain the remarkable efficiency of the public housing programs. However, the authoritarian attitude of such organizations has resulted in high social, urban, and environmental costs.

2.2. Planning and housing design in modern China

As in most socialist countries, national government policies have shaped the direction of Chi na's development (Kim, 1987). Since the Revolution, the important changes in the Chinese socio-political environment have influenced national urban development policies. These forty years can be divided into six major periods: the Reconstruction Period, the First Five-Year Plan, the Great Leap Forward, the Recovery and Consolidation Period, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the Post-Cultural Revolution Period and the Open Door Policy (Hoa, 1981) (Yichun & Costa, 1991). This section presents the evolution of planning approaches and of the main housing prototypes through the diverse ideological changes that have taken place in China since 1949.

a) Reconstruction Period (1949-1952)

On the first day of October 1949, from his high tribune on Tian An Men square, Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China. For the Chinese, this represented the end of over 100 years of wars and upheavals, and the restoration of the country's unity (Hoa, 1981). Eager to gain the population's trust and faith by demonstrating its concern and efficiency, the new govern ment immediately launched a series of programs to reconstruct and reorganize the country (Hoa, 1981).

One of the first achievements of the Party in the field of housing was the nationalization of housing and the introduction of the equalization process in the early 1950s. Private homeowners were allowed to keep the portion of their dwelling necessary to house their family and the rest of the housing was confiscated by the state and distributed among the population.

Although urban population increased significantly during those years due to rural exodus and substantial urban growth, the construction of housing was not a national priority (Kwok, 1979). First priority was given to reconstruction of the infrastructure damaged during the war, and to catching up with the rest of the modern world, laying the foundations for the rapid industrialization of China (Léonardon, 1979). Urban design practice was left unchanged from that of before 1949, and the production of housing was characterized by temporary construction responding to immediate needs. Architects and planners were required to be pragmatic and to disregard aesthetic concerns in order to concentrate on functionality and economy (Kwok, 1979).

Since there were no precedents for mass housing in China and the notion of apartment build ings was still new, most housing produced during that period was in the form of single-story, continu ous row housing (Léonardon, 1979). This was the simplest and fastest way of building, and resembled the ground-related traditional dwellings (Hoa, 1981). The long houses had a full north-south orienta tion, with independent or grouped rooms, and a front yard. Soon, two-story structures following the same model, with an external corridor replacing the front yard on the second floor, were introduced in order to save land (Hoa, 1981).

b) First Five-Year Plan (1953-1957)

According to Léon Hoa (1981), China's recovery was completed after only three years. In 1953, in virtually all major domains, production surpassed the highest levels ever achieved before Liberation. The situation was thus favorable for the implementation of the First Five-Year Plan, which was launched in the early days of 1953 (Hoa, 1981).

The Soviets had a strong influence on the realization of this first plan because of their political ideology as well as their twenty years of experience in urban planning. China was starting from zero (Hoa, 1981). The Soviet planners shifted focus to the development of strategies and planning concepts, giving priority to the strengthening of urbanization, development of suburbs, and urban renewal through slum clearance (Kwok, 1979). The development of heavy industries was also emphasized (Hoa, 1981).

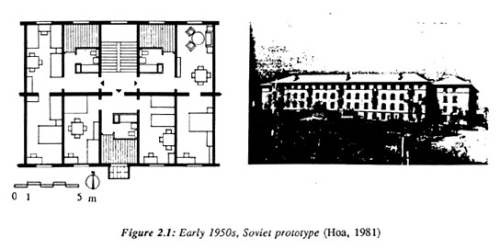

Concerning housing design, the 1949 temporary type was abandoned and systematic studies for large-scale projects and standardized housing were conducted (Hoa, 1981). The first prototypes con sisted of three- to five-story apartment buildings arranged on large open spaces. The building form was simple and classic, and regularity and symmetry were encouraged. Apartments had comfort facilities equipped kitchens, large bathrooms and central heating but were unnecessarily large and did not receive sufficient sunlight (Hoa, 1981). The idea behind such large apartments was to plan for future comfort, but for the time being, two families would have to share one apartment (Léonardon, 1979). As illustrated in figure 2.1, rooms were designed deep and narrow, with uncomfortable proportions, with concern for heat conservation.

Such design, based on Russian norms, did not respect Chinese living habits, especially with respect to privacy and the separation of room functions 12 (Léonardon, 1979).

c) The Great Leap Forward (1958-1961)

This period represents a turning point in modern Chinese history. It is characterized by an increase of Chinese autonomy and the end of good relations with the Soviets, which led the way to years of experimentation and local technological development (Léonardon, 1979). The proposed strategy advocated the abandonment of foreign concepts and concentration on the development of local and indigenous techniques addressing local needs, using local resources and avoiding ready-made solutions (Hoa, 1981). Emphasis was on quantity, quality, speed and economy, seeking to increase production while reducing investment (Hoa, 1981).

During the years 1958-1959, efforts were concentrated on industrial production and agriculture was neglected, which resulted in great reductions in harvests. In 1959, 1960 and 1961, China experienced a succession of natural calamities, including droughts and consecutive cold winters. As a result, China was thrust into a great economic depression (Yichun & Costa, 1991). The sudden departure of the Soviets in 1960 translated into the loss of foreign advisers and the disappearance of essential resources and supplies, and also contributed to the crisis (Hoa, 1981).

Urban population growth was considerable during this period 13. The principle of registration (hukou) was introduced in 1958 to control urban migration, and surplus population was transferred to rural areas (Kwok, 1979). Abundant and relatively cheap labor triggered an unprecedented large-scale construction process (Léonardon, 1979). Principal building activities were devoted to the construction of factories and housing for workers in the suburban areas, where the new industrial complexes were developed (Kwok, 1979). In the housing field, the new strategy was to house a maximum number of people in minimum space with maximum comfort and at minimum cost (Hoa, 1981).

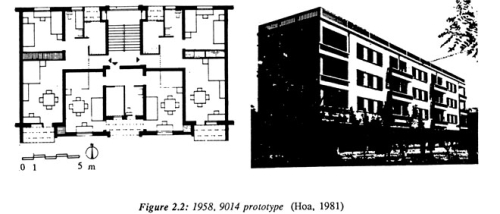

Most housing projects built during this period were based on the modification of the first Soviet prototypes. The first adaptation was the so-called 9014 plan, illustrated in figure 2.2 (Hoa, 1981). It had basically the same layout as the Soviet prototype, but with better proportions and systematic north-south orientation. A square lobby was introduced as well as a balcony or a loggia and a closet for storage (Léonardon, 1979). This new apartment type was very popular throughout China, although it was still excessively large (between 65 and 73 square meters) (Léonardon, 1979). The new structural system with transversal bearing walls allowed for more economic floor slabs, better seismic resistance and greater freedom for positioning openings in the facade.

|

__ |

The 9014 plan was soon abandoned and replaced by a new model with a similar layout but smaller rooms. The bathroom was removed and replaced by a water closet. With this new design the floor area for a two-room apartment could be brought down to forty-six square meters, as illustrated in figure 2.3 (Léonardon, 1979). In the long run, the stress put on cost reduction led to a major de crease in quality. The new apartments had mediocre standards with thinner walls, lower doorways, no bathroom, no heating, shared toilets and sometimes not even a kitchen (Léonardon, 1979).

d) Recovery and Adjustment (1961-1966)

As the country's economy experienced tremendous hardship during the Great Leap Forward, the next period was one of readjustment and consolidation (Kim, 1987). The period is thus character ized by great shifts in direction regarding development priorities, with more emphasis on rural development and industry and less on urban concerns (Kwok, 1979).

The reorientation of priorities resulted in an almost complete halt in housing construction, allowing for a period of reflection during which professionals had the opportunity to conduct research on modern and traditional housing (Léonardon, 1979). Surveys on housing projects and standard building elements were conducted, as well as systematic interviews of dwellers (Hoa, 1981). This experimenta tion and evaluation period allowed for the collection of information essential for future project design (Kwok, 1979).

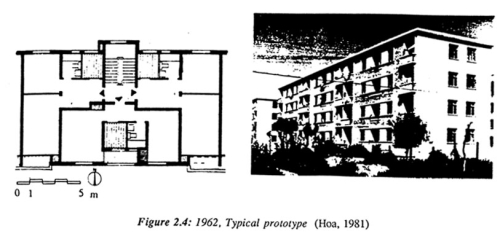

In 1962, China's economy was stabilized (Hoa, 1981). After three years of intensive research, professionals were ready for a readjustment and standardization of the housing production. The industrialization of construction allowed for mass housing projects to be built more quickly and more eco nomically. Improved prototypes were developed with the introduction of reinforced concrete elements, which were produced on a large scale and sold on the open market. Housing quality was improved but remained inferior to that of the Soviet years (Léonardon, 1979).

_

_

As illustrated in figure 2.4, each unit was composed of two main rooms, a kitchen, a shower, a lobby, and a balcony. The year 1962 thus reflected a certain maturity in housing production which struck a balance between too high and too low standards. After 1964, new directions were taken in mass housing production to reduce costs substantially. A new cost-cutting approach was introduced and a series of very low standard plans emerged (Léonardon, 1979).

e) The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)

In 1966, a series of reforms in all domains was launched and led to what was called the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The proposed reforms, which offered a new perspective on socialism, initially sounded very appropriate and had an incredible appeal in China as well as in the rest of the world (Hoa, 1981). The main objective of the Cultural Revolution was mobilize the masses and to redevelop their revolutionary consciousness (Kim, 1987). But soon, exaltation and fanatism led to a massive rejection of tradition, discipline, and all types of representations of power or elite. This brought the country to a state of quasi-anarchy and to the edge of bankruptcy (Hoa, 1979). Most universities and research centers were closed down between 1966 and 1970 and a large number of documents and archives were lost or destroyed (Hoa, 1979).

During this period, great importance was placed upon political ideology and cultural conformity. The focus was on production-oriented, industry-related buildings, and efforts were concentrated on the development of appropriate technologies and progress in rural areas (Hoa, 1981). As a result, housing production and design were neglected, public construction was reduced to a minimum and city planning offices were entirely closed down (Hoa, 1981).

Throughout the Cultural Revolution, the quality of urban housing production remained very low. The cost-cutting approach was reintroduced, leading to a drastic decrease in comfort level, which eventually reached the lowest housing standards ever seen in China.

The plans were simplified, apartment sizes were greatly reduced, and most buildings had external corridors (Léonardon, 1979).

_

_

Walls were thinner and insufficiently insulated, central heating disappeared and toilets had to be shared. Figure 2.5 gives an example of such prototype. Some designs explored the possibility of housing one family in a 3 x 8 meter module (Léonardon, 1979).

After 1971, the frenzy of the first years of the revolution began to calm down. In 1974 and 1975, the situation returned to normal, professionals were rehabilitated and production started again. The extreme cost-cutting trends were rectified, and new plans with ingenious layouts were introduced (Hoa, 1981). Figures 2.6 and 2.7 give two examples of apartments built during these years. In the same period, high-rise apartment buildings also ap

peared in China (Hoa, 1981).

_ _ |

|

f) Post-Cultural Revolution Years (1976-1979)

In October 1976, after ten years, the Cultural Revolution, considered by some to have been an uninterrupted disaster for Chinese society as a whole, finally came to an end (Kim, 1987). The year 1976 also featured the death of Mao Zedong and the fall of the Gang of Four (Kwok, 1979). The new period was one of reflection and reassessment, and efforts were made to carry out policies of reform, consolidation, and improvement. Western concepts were reintroduced, along with the notion of urban renewal (Yichun and Da Costa, 1991). Construction activities and the production of prefabricated elements that had been almost paralyzed since 1967 slowly started functioning again.

_

_

Land shortage became an issue as it was realized that between 1949 and 1960, 50% of agricul tural land around major cities had been taken over by urban expansion (Hoa, 1981). This justified the construction of new twelve- to fourteen-story apartment buildings throughout the country (Léonardon, 1979). In fact, very few buildings constructed during that period had fewer than five stories (Ekblad, 1990). The comfort level was brought back to that of 1962, but with relatively smaller rooms, as illustrated in figure 2.8.

g) The Open Door Policy (1979-1990)

Since the late 1970s, China has been moving in a new direction. At the Third Plenary Session of the Chinese Communist Party's Eleventh Central Committee in December 1978, Deng Xiaoping proposed a series of reforms that reflected a shift in national priorities (Fong, 1989). The new Open Door policy was introduced, leading to China's opening to the world and to the introduction of interna tional concept at all levels (Kim, 1987). The new national goal was to achieve the modernization of industry, agriculture, science and national defense by the year 2000 (Slater, 1981).

In 1981, Chinese authorities restated the goals of the reforms and set basic limits to moderniza tion: city size was to be limited, private automobiles would be discouraged in China, and the free market would not be permitted (Slater, 1981). Restrictions on popular movements in major cities were relaxed, but still strictly controlled (Kim, 1987). The Housing Reforms 14 were introduced and housing became a stated priority. Municipalities and enterprises were asked to contribute to the production of housing and to use their own funds to build housing. As a result, public funding for housing were tripled after a few years and unprecedented rates of housing construction were reached (Hoa, 1981).

The post-Mao era transformed China from a rigid and traditional socioeconomic and political structure to a more flexible and adaptable modern state (Kim, 1987). People's living standards im proved as the industrialization of the country proceeded.

Housing production had to adapt to this increase in demand for more space, for a larger number of rooms, and for improvements in services, facilities, and equipment. With the introduction of refrigerators, washing machines, televisions, and furniture into many homes in the early 1980s, existing units no longer met the needs of the population (fig. 2.9). Designers had to find ways of accommodating a growing number of people, while at the same time preparing for future improvement in comfort.

The prototypes built in the early years of the modernization period reflected the use of new techniques and building materials and the introduction of new theories and building forms. The use of concrete elements for the entire construction became widespread. A more effective use of the interior space was shown in the apartment layout with the enlargement of the living room and the reduction in size of the bedrooms. Bathroom design, natural lighting, and ventilation were improved. The average story height, which had been 3.2 meters in the early days of the People's Republic, was brought down to 2.6 meters.

Today, most planning practices for modern residential areas used in China are based upon Western planning theories. The Modernist ideas of city planning and building developed in the 1920s in the work of Le Corbusier have found solid support in new China (Fig. 2.10) (Solvic & Ligia, 1988). Sixty-three percent of all existing housing in Beijing is now in the form of multi-storied apartment buildings15 (He, 1993).

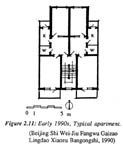

The most common type of low-cost housing currently built in China is a six-story walk-up apartment block (Zhou Wenzhen, 1983). Typical apartments consist of through units with a north -south orientation and two multi-purpose rooms. Services are usually grouped on the north side, while main rooms face south. A small central distribution hall is also used as a dining or living room (Zhou Wenzhen, 1983). Entry stairs are generally placed on the north facade and two to three units are accessed on each floor. Figure 2.11 gives an example of this typical apartment type.

(Lampugnani, V.M. ed. Encyclopedia of 20th-Century (Beijing Shi Wei-Jiu Fangwu Gaizao Architecture. New York: Abrams, 1986: 195) Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi, 1990)

Although they have been discredited for public housing in the West since the 1960s, high-rise apartment buildings have gained the approval of a large number of planners and designers in contem porary China16. Mass housing and high-rise buildings are held in high esteem, as they represent Chi na's drive towards modernization. The resulting urban skyline is the pride of local authorities (Yichun & Da Costa, 1991).

Since 1988, the Ministry of Construction has been attempting to popularize pilot projects in residential quarters and to encourage planners to create more imaginative projects and the integration of local features into the design (Wang Dehua, 1992). Researchers and planners are now starting to look for ways to develop prototypes of low- and medium-rise buildings which achieve high densities with a more integrated form of development (Wu Liang Yong, 1991).

2.3. The current housing system in China

In China, the production of housing is very rigid and centralized. This section provides a syn thetic overview of the main social, political, economic and technical issues involved in the housing production process, to provide a better understanding of the complexity and multiplicity of its mecha nisms.

a) The Housing Process

Housing is a politically charged subject in China. The Chinese Communist Party's conviction that housing in a socialist state should be a social welfare provision that seeks only nominal returns led to the present housing system (Yok-Shiu, 1988). The state is thus responsible for the provision, allocation, administration, and maintenance of all housing, however heavy the burden of this responsibility (Chen, Lijian, 1988).

Although all land in China is owned by the State, housing ownership falls into three major categories: housing owned by the municipal government; housing under the management of various work units (danwei)17, which are divided into state-owned and collectively-owned enterprises; and private housing (Chen, Lijian, 1988). Housing under the management of state-owned work units rep resents the majority of houses (Wang Yukun, 1989), while between 15 to 20 % of urban housing is owned by the municipal government (Kim, 1987). Work units provide housing to their employees, and local governments generally accommodate people who are not attached to a particular work unit. Before 1978, private ownership was restricted to people who owned their house before the revolution. Private ownership is now encouraged as the commercialization of housing allows people to buy their own apartment.

Most dwellers in China are tenants who rent their apartments from their work unit or from the local government. Rents are highly subsidized and are generally very low, with annual rents covering only 0.08% of total building costs (Chang, 1987). People spend between one and three percent of their household's income on rent, and about the same amount for electricity less than the price of a pack of foreign cigarettes (Ekblad, 1990)18. Utility companies supply water, electricity, and gas and bill the residents each month. Rent delinquency poses no problem. If a resident fails to pay rent, the work place is informed and the amount owed is deducted from the worker's pay (Friedman, 1983). A scoring system based on the applicants' current living condition, household size, seniority in service, position held, and contribution to the work unit, determines the priority and size of living space to be assigned (Fong, 1989)19. The control of housing by work units and the local government has led to a high degree of residential stability. According to a 1984 survey, only ten percent of the population changed resi dence in five years and the average time spent in one house was eighteen years (Joochul, 1987). Tenants cannot be moved unless provided with accommodations (He, 1990).

Local governments are generally in charge of housing planning and construction. They follow standardized modes of construction and use building materials produced by state-owned companies (Slovic & Ligia, 1988). Each city district has its own local government and individual planning and design bureaus. Nearly all housing projects are designed and engineered by the state-owned Institutes of Architectural Design and built and finished by the Institutes of Construction (Slovic & Ligia, 1988). Occasionally, students in the schools of architecture and planning are also involved in project design 20. A few state-owned companies monopolize all the housing construction in each city. That no individual takes responsibility for design and execution can explain the lack of originality in the design and its poor physical quality.

Formal training in architecture is a relatively new phenomenon in China 21 and the practice of architecture is highly restricted. The rigidity of the production system, with its bureaucratic process, its standardized housing units and its monopoly on construction has constrained the role of design profes sionals. Diverse ideological influences are also reflected in the design 22 (Rykwert, 1993). Today, the need for rapid and massive project implementation has reduced the time allocated for project design. As a result, projects are implemented without site analysis or impact studies, ready-made plans are still used and entire projects are often replicated.

Construction companies are generally in charge of general building maintenance during the first year following the completion of a new project. This responsibility is then passed on to the city districts' local government management bureaus, which are also responsible for the maintenance of outdoor collective spaces. Neighborhood committees 23 organize resident to take care of the interior common spaces.

b) Building Regulations

In China, building regulations vary from region to region. In Beijing, the main regulations for residential project design are related to building height, sunlight, apartment size, building density, and earthquake resistance.

In the inner city of Beijing, building height regulations vary according to proximity to the historic core and the Forbidden City. In historically sensitive areas, buildings are restricted to two or three stories. Elsewhere in the inner city, buildings can be up to six stories high. Outside the old city walls, regulations are not as strict and high-rise buildings abound. Concerning sunlighting, regulations require that all main rooms have at least one hour of sun on December 22nd, the shortest day of the year24 (IAURIF, 1987).

Due to the severe housing shortage, the Chinese housing authorities have adopted fairly strin gent norms regarding per capita living area25 (Bhatt et al., 1993-I). The number of rooms per unit, the total area of the unit and the distribution of apartment types in a project are specified in the regulations. National regulations for urban housing require that each person be provided with seven square meters per person, but the actual situation in major urban centers is even worse (Bhatt et al., 1993-I). One of the main goals of the Eighth Five-Year Plan is to bring the per capita living area in urban areas up to eight square meters by the year 2000.

In China, the floor-area ratio, or FAR 26, regulates residential project density and serves as an important measure of the optimum utilization of land. Developers often use the FAR to compare the profitability of projects and base their choice upon achievement of a high FAR. They will generally invest in projects with a FAR of no less than 1.5 (He, 1990). In the inner city of Beijing, the FAR is set at 3 (He, 1990). Since 1976, regulations regarding earthquake resistant structures have been imposed in the Beijing area.

c) Main Construction Systems

China's current level of industrialization favors construction systems which make use of semi-traditional materials such as bricks and hollow blocks (Xu Ronglie, 1988). For decades, small clay bricks have been the principal building material used in China 27 (McQuillan, 1985). The main construction systems currently used are the traditional brick or block masonry system, the cast in-situ system, and the frame and panel system.

The most prevalent structural form of housing is the brick-and-concrete multistoried building, which represents 80% of urban housing (Xu Ronglie, 1988). Solid clay bricks are used for all interior and exterior load-bearing walls, whereas hollow clay bricks may be used for non-load-bearing parti tioning walls (Zhou Wenzhen, 1983). Reinforced hollow concrete slabs are used for the floors (Xu Ronglie, 1988). Exterior facades may or may not be plastered. This system is adaptable to low- and medium-rise buildings which are from five to eight stories high (Chen and Yu, 1985). It is favored because of its low-cost, traditional technique, its simplicity of operation, and because all material can be acquired locally (Kwok, 1981). However, brick masonry is high in labor intensity and low in efficiency, which results in a long construction period. Burning of bricks is also highly consumptive of energy, and the production of clay bricks causes great damage to agricultural land (Xu Ronglie, 1988).

The medium and small size concrete block masonry system is also widely used, accounting for about 15% of total housing currently built (Chen and Yu, 1985). Blocks of various sizes are manufac tured with the use of local industrial wastes and indigenous material available. This system is similar to the brick masonry system and is suitable for medium- or multi-story buildings. It is simple in fabrica tion and building technique, and similar in construction cost and efficiency to that of brick masonry (Kwok, 1981).

Another building system currently used consists of the cast-in-situ concrete system for interior walls with masonry exterior walls. Reinforced concrete interior walls are cast in-situ with gang forms while the exterior walls are either brick or block masonry. Sometimes exterior walls can also be made of cast in-situ concrete or prefabricated panels. In this system, all interior walls are load-bearing, while exterior walls serve only as enclosures. Floor slabs are made of precast reinforced concrete compoents. The system can be adapted to buildings of up to eight stories. This system has the advantages of being a fast-growing system which is structurally sound and resistant to earthquake. In addition, it can be left unplastered. However, this system allows for little flexibility in layout and requires the use of heavy duty hoisting machines (Chen and Yu, 1985).

With the emergence of high-rise buildings, framed construction with lightweight wall panels was developed in China. Buildings varying from eight to twenty-four stories high can be built with a load-bearing reinforced concrete frame and light-weight panels for partition and enclosure walls (Chen and Yu, 1985). Panel components are mostly factory prefabricated. This system has the advantage of being flexible in its plan layout, but it is both complicated and expensive to use.

Since the early 1970s, construction quality has been improving gradually, but has resulted in a substantial increase in construction costs. The cost of labor is very low in China 7% of total con struction costs while material costs are high as much as 80% of total building costs (McQuillan, 1985). Between 1972 and 1982, construction cost per square meter increased by 135.8% (Yok-Shiu, 1988). Today, a square meter of traditional masonry construction costs approximately 300 yuan 28 (Kim, 1987).

2.4. Problems in the housing system

Although it has been given first priority by the Chinese authorities, the housing shortage re mains problematic in China. In recent years, serious housing inequalities have also emerged from the system (Chen Lijian, 1988). The shortcomings of the current housing system are discussed in this section, along with their possible causes.

a) Housing Shortage

In the last few decades, China's urban centers have faced a severe housing shortage which has resulted in serious overcrowding and has forced the great majority of the population to live in sub standard conditions29.

Besides inadequate urban and regional planning and insufficient state invest ment, the urban housing shortages can be seen as the result of the current low-rent policy and the highly centralized building industry (Yok-Shiu, 1988). Figure 2.12 illustrates overcrowded housing in China.

The welfare housing policy that has prevailed since the Revolution has greatly affected the housing situation in China. Highly subsidized rents are not sufficient to amortize the cost of new construction. Mediocre building quality and lack of funds for proper maintenance of the existing urban housing stock accelerated housing deterioration and reduced building life (Fong, 1989).

The inefficiency of the current building industry has also played a part in the housing shortage. Its low level of technology and the shortage of manpower qualified in construction, organization, administration and planning have limited the rate of housing production (Dwyer, 1986). A lack of systemization of the building process due to the absence of coordination of the whole construction industry, and the scarcity of modern building materials, also explain the low efficiency in housing construction (Kwok, 1981).

b) Housing Inequalities

The current housing system has given rise to diverse forms of housing inequalities. One's position in gaining access to housing depends to a large extent on the type of work unit to which one is attached (Fong, 1989). State-owned enterprises have more resources for housing than any private or collectively-owned work unit (Yok-Shiu, 1988). As a result, people who are self-employed or not attached to a specific work unit often face serious housing problems (Chen Lijian, 1988). Low rents also encouraged some people to secure more housing than they were entitled to. Similarly, rent subsi dies are not distributed according to each household's financial needs (Yok-Shiu, 1988). They are given out by the state on a square-meter basis, regardless of the size of a household's living area. Therefore, people with larger apartments enjoy a larger government subsidy and there is a built-in incentive for urban residents to secure housing with the maximum amount of floor space (Yok-Shiu, 1988). The recent construction boom and the commercialization of housing have exacerbated the ex isting inequalities (Chen Lijian, 1988).

2.5. Housing reforms

In 1979, the Chinese government launched the new Open Door Policy, and, in its quest for modernization, introduced a series of economic reforms. The reforms were to allow the market forces and private enterprises to play an increasing role in the production and consumption of goods, following the world trend in the privatization of public services (Fong, 1989).

By 1981, the Commercialization of Housing Reform Policy was introduced to decrease hous ing subsidies and to stimulate China's construction industry (Fong, 1989). The initial goal of the hous ing reform was to establish an equitable and efficient system to solve the housing shortage problem and to convert the heavily subsidized house-building industry into a self-financing business (Fong, 1989). It was intended not only to relieve much of the State's burden, but also to help curb inflation and stabilize the economy (Barlow and Renaud, 1989). The reform also aimed at the decentralization of decision-making concerning housing production (Chen, Lijian, 1988).

The privatization of housing was announced as one of the most important objectives of the housing reform, which was to gradually transform housing into a commodity30 (Ke Jian Min, 1987). Ideologically, housing was no longer to be treated as a welfare service but as a personal consumption good, with household savings playing a larger role in housing finance 31 (Tolley, 1991). In 1985, the government launched a rent reform policy whereby rents would be readjusted to cover the costs of maintenance and management and would comprise a larger proportion of a family's income 32 (Fong, 1989).

Over the years, the housing reforms have been slowly implemented, but they have not yet produced the expected results nor fulfilled their original goals. Low wages and lack of aid in the form of bank loans or mortgages have hampered the successful implementation of the commercialization scheme. Even when highly subsidized, the new units remain too expensive for the majority of the population and with the current low-rent policy it is still more convenient to rent an apartment than to buy it (Zhu Yan, 1989). Another problem is that the state still regulates ownership to prevent specula tion and that home-buying is still not equated with home-ownership in China. Residents buying their units at a subsidized price are not allowed to sell or exchange it in the first five years. After five years, the house can only be sold back to the local government's management bureau or kept and passed on to the next generation by inheritance. Similarly, rent reforms have not been fully implemented. Until now, rents have been only slightly increased and are still far too low to cover basic costs. Even though there has been a large increase in the average per-capita income, 33 the percentage of income spent on housing is still extremely low (Yok-Shiu, 1988).

The government's failure to fully implement the housing reforms can be explained by political as well as economic reasons (Yok-Shiu, 1988). For the government, changing the socialist definition of housing is a sensitive issue34. The Open Door policy introduced elements of capitalism into the system, but the government remains on guard against their potential outcomes such as high infla tion and corruption (Fong, 1989). The complete restructuring of the rent system would require a total rearrangement of the economic system and must be tied in with some type of wage reform so that people's living standards would not be seriously compromised (Chen, Lijian, 1988). Implementing the housing reforms would also require the transformation of the housing policies and the readjustment of national housing standards (Yok-Shiu, 1988). Some of Beijing's officials estimate that it would take ten years to fully carry the reforms in the capital (Zhou Ganzhi, 1988).

Being more familiar with the complexity of the housing process in China, the reader is now ready to learn about the recent phenomenon of neighborhood regeneration in Beijing's old neighborhoods, which is presented in the following chapter.

1 The early resettlement estates consisted of six-story, H-shaped blocks, with back-to-back units accessed from open balconies running around the block. Cooking was done on the balconies and washing and toilet facilities were communal. Elevators and electricity were generally lacking.

2 The Ten Years Housing Program soon appeared over-ambitious and was extended until 1985.

3 The Hong Kong Housing Authority was formed by integrating all functions in public housing from policy formulation, financing, planning, design and construction of housing, and allocation and maintenance of housing stock, to management of the housing estate into one department. The housing Authority is responsible for its own finance and management. The government subsidizes the public housing program by providing free land and loans to finance projects. Today, the Housing Authority possesses one of the largest public housing stocks (over 550,000 rental apartment in 1987) (HKHA, 1987).

4 For example, a mortgage system, covering up to 95% of the purchase price and spread over twenty years, with a maximum interest of 9% per year, was introduced (HKHA, 1987).

5 Eventually, 90% of the population is expected to be housed in public housing, leaving the remaining 10% in expen sive but status-enhancing private properties (Castells et al., 1990).

6 The scope of HDB activities include the planning of new towns and town centers as well as the design and construc tion of housing and other facilities. The HDB is also involved in the production of building materials and undertakes large reclamation projects. It is responsible for the maintenance and management services of the housing estates as well as for the upgrading of older estates. HDB designs and supervises its own projects. The HDB housing program is entirely financed through government loans. Subsidies are also allocated to small dwelling units usually occupied by poorer families. The HDB does not, however, have its own land bank. It has to bid for land from the authorities, in competition with other government agencies and users, and has to pay for the land at an agreed-upon negotiated price (Schmidt, 1989).

7 The early estates consisted of emergency slab blocks with one- and two-room units linked by a double-loaded corridor. Later, slab blocks changed to a single-loaded deck access corridor design. A segregated corridor design was developed to provide for greater social interaction and neighborhood surveillance against crime.

8 Units were sold on a ninety-nine years lease, to be occupied by the owner for a down payment of about 20%, the balance to be repaid over a fifteen-years period at 6.5 % interest.

9 Initially, to be eligible an applicant had to be part of a family of a minimum five persons. When the housing shortage eased, the number was reduced to three. Today, with a rapidly declining birth-rate, a series of incentives was introduced to promote the reinstitution of the traditional family structure. Larger families are now favored when flats are allocated (Siew -Eng, 1989).

10 Originally, HDB units could only be sold back to the HDB at their original price.

11 Over 30% of the Hong Kong total annual capital expenditure and 10% of the annually recurrent expenditure is devoted to the development, maintenance and subsidy of public housing. This compares favorably with anywhere in the world and far exceeds the 5-6% public expenditure generally accepted as being a desirable target for developing countries (HKHA, 1987).

12 In most traditional oriental dwellings, the allocation of specific functions to different rooms is a foreign concept, and rooms generally serve various functions. In the current Chinese context, the great shortage of space resulted in that most rooms are used as living rooms during the day and bedrooms at night. The term bed-living room is often used to describe the main rooms in the Chinese housing.

13 Migration from the countryside to major cities continued and the urban population increased from 92 to 130 million between 1957 and 1960 (Kim, 1987).

14 The housing reforms will be discussed in detail in section 2.5. of this chapter.

15 According to Chinese specifications, high-rise buildings have between ten and thirty stories, mid-rise buildings seven to nine, multistoried buildings between four and six , and low-rise buildings are between one and three stories high ( Song, 1988) (Liu & Li, 1988).

16 They now account for 30% to 50% of urban housing and average twelve to fourteen stories (Dixon, 1989). In Beijing, most high-rise buildings are eighteen stories or more (Mann, 1984).

17 The work unit (danwei), wrongly translated as enterprise, is a very important institution in socialist China. Accord ing to Kim Joochul, associate professor at Arizona State University, the work unit constitutes the basic unit of the social organization, central to the daily life of most workers. Work units are supposed to provide lifelong employment, health insurance, social security and housing for their employees (Kim, 1987).

18 In comparison, in developing countries at similar levels of development, households spend around 8.6% of their income on rent monthly; the average is 15% in developed countries (Li Ping, 1991). In the last thirty years, the average expenditure of urban households on rent has decreased steadily (State Statistical Bureau, 1988). In 1957, a family spent, on average, 2.3% of its income on rent, whereas in 1985, the figure was 1.1% . During the same time period, the expenditure on housewares increased from 8 to 20% (Fong, 1989).

19 For example, a three- to five-person household would be allocated a two-room unit and a six- to eight-person household would get a three-room apartment (Friedman, 1983). Young couples are not eligible for new housing and have to live with their parents if their combined ages do not add up to fifty years (Dwyer, 1986).

20 Since 1958, students in the different schools of architecture have been involved in the conception of actual projects, in the frame of what is called the real sword and real spear design thesis (Gao Yilan & Liu, 1981).

21 Traditionally, the business of building was divided among masons, carpenters and potters. It was not until 1930 that a group of young Chinese architects, recently graduated from American schools, created the first professional body, the Chinese Architectural Society (Sun, David Paul, 1989).

22 The Beaux-Arts tendencies of the first returned scholars and the influence of Le Corbusier's planning ideas set the trend for the Chinese modern architecture. After the 1950s, most architectural production was influenced by communist ideology and justified in populist terms, as an attempt to appeal to the masses (Zhu Youxan, 1986). Today, the successful examples of Hong Kong and Singapore serve as the new models for housing design.

23 In urban areas, each block or street has a neighborhood committee, which serves as an intermediary between local political organizations and family units (Liu Zhuyuan, 1989). The committees are responsible for public security and public health, mediation of civil disputes, and maintenance of public order. In addition, they are in charge of conveying the residents' concerns about public affairs and social services to the People's government (Friedman, 1983). Most of the members of the committees are retired women who receive subsidies from the government.

24 In Beijing, this translates into a H to L ratio of 1:1.7, where H is the building height and L the distance between two buildings. The strict application of this rule reduces the flexibility in project layout and has resulted in the generalization of north-south oriented buildings.

25 Housing areas are generally expressed in terms of built-up area, and living area. The built-up area includes kitchens, rest rooms and balconies and the area for vertical and horizontal common circulation space, as well as the area occupied by the walls. Living area consists of the calculation of the area of the rooms used for living. It excludes kitchens, rest rooms and balconies (Liu & Li, 1988).

26 Floor area ratio (FAR) sometimes called plot ratio or floor space index, consists of the ratio of built-up area above grade to site area (Lynch and Hack, 1985). It is commonly used as a measure of development intensity. Various housing prototypes achieve different FARs. In general, traditional courtyard houses reach an average FAR of 0.5, without taking the self-built additions into consideration (which increases the FAR to up to 0.75). Alternative forms of housing reach FARs varying from 1.5 and 2.5, whereas mass housing projects may reach an FAR of as high as 6 (He, 1990).

27 There are more than 1,800 brick plants in China where small clay bricks are machine-pressed or handmade (Xu Ronglie, 1988). However, since most building materials are under centralized planning control in China, there is no formal market for the people to buy them.

28 In 1993, the average salary in greater Beijing was around 300 yuan a month, representing an income of 600 yuan per household (the 1994 rate is about eight yuan for one American dollar). In central Beijing, this figure is thought to be slightly higher. The average salary of a professor in China is 250 yuan per month (Bhatt et al., 1992).

29 Only 7.9% of households of the inner city of Beijing have a per capita living area of more than ten square meters (Chen, Lijian, 1988). Each year, over two million newly married couples are waiting just to get a room to live in (Ke, 1987).

30 Stalin, in his 1952 work entitled Economic Problems of Socialism in the U.S.S.R. , divided goods into producer goods and consumer goods, and identified consumer goods as commodities, which can be sold at a profit (Kojima, 1987).

31 For two generations of Chinese, housing has been seen as a public good rather than a commodity. The Chinese have recently begun speaking of shangpinfang, or commodity housing, i.e. housing sold to private parties, at fixed prices, for private ownership (Kojima, 1987).

32 For example, in Beijing rents are to be increased in a three-step process. Rents that used to be set at 0.13 yuan per square meters (often referred to as the old rent ) have already been raised to 0.27 yuan per square meters and should reach 0.55 yuan per square meter (referred to as the new rent) in the near future (Fong, 1989).

33 Since 1978, the income of China's urban residents has risen rapidly and its sources have diversified. Apart from their regular wages, which have risen substantially, the balance of people's revenue has come in the form of bonuses, subsidies, dividends on shares and floating wages. These represented about 34% of the income in 1988 (State Statistical Bureau, 1988).

34 However, Engels, in his article "On Housing Problems", considered housing transactions to be a form of economic law also subject to the mechanisms of supply and demand, thus recognizing that the notion of housing as a commodity can apply not only to a capitalist economy but to a socialist economy as well. (Zhang Xianqu, 1986).

[ TopOfPage(); ]