Are you kidding me? “Nature’s Ozempic"? Really? That message is spreading like wildfire on TikTok about berberine, a compound found in plants such as barberry, golden seal and meadow rue that have a long history of use in Ayurvedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Why the comparison with Ozempic, Novo Nordisk’s brand name for its anti-diabetes drug, semaglutide? Because semaglutide has turned out to have an unanticipated side effect. Weight loss! That unforeseen outcome stimulated randomized, double-blind clinical trials in which semaglutide helped participants lose as much as fifteen kilograms over sixteen months. Given the number of people who dream of reducing their girth, and the rather dismal historical performance of weight control drugs, it isn’t surprising that Ozempic has blasted its way into headlines. Neither is it surprising that various Ozempic wannabes have tried to jump on the drug’s coat-tails. Since semaglutide is expensive, running at around $1000 for a month’s supply, there’s a sizeable population ready to be snared with an offer of a cheaper version. Especially if it is anointed with the magical marketing term of “natural.”

Berberine may indeed be “natural,” not that this has any relevance. Just ingest some “natural” aflatoxin B from a mold growing on some improperly stored grains and see how quickly you lose weight. But that will be because of the cancer sparked by this “natural” toxin. Neither is berberine any version of Ozempic, which is an analogue of glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP-1), a natural hormone that regulates blood sugar and helps people feel full. Berberine has nothing to do with GLP-1. How then has this compound been dredged out to become the darling of the Tik Tok crowd?

It is hard identify ground zero for berberine as a supposed weight control substance, but a reasonable guess is that someone seeing the Ozempic bandwagon accelerate as it rolled by had the idea of scavenging through the scientific literature to find some substance that could be passed off as a bargain-basement relative. That bit of fool’s gold was likely found in a review paper published in “Clinical Nutrition ESPEN,” an Iranian journal with an impact factor of 0.67, which means that papers published in the journal are hardly ever cited by other scientists.

In any case, the article in question was a review paper by Iranian scientists of all the publications they could find in the scientific literature that had in any way related the use of berberine to weight control. They found twelve, all in low-impact journals. Nine were in Chinese publications, and one each in an Italian, Mexican, or Iranian journal. The studies spanned anywhere from one to four months and recorded an average weight loss of about four and a half kg. Now for the “buts.”

Significantly, none of the studies tested berberine in subjects whose only problem was overweight. The studies involved subjects, rather small numbers in each case, who had diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), coronary disease or had kidney transplants. The dosage of berberine ranged from 300 to 1500 mg a day, and in some studies other drugs were also used. Basically, it is not possible to tell whether any weight loss that occurred was due to berberine or disease. Furthermore, no dose-response relationship was documented, so one cannot conclude from these studies that berberine is “nature’s Ozempic.”

But let’s not throw out the baby with the bathwater. Berberine may not help shed pounds, but it may yet make it into pharmacies as an effective medication. At least, some derivatives of berberine may. Drug discovery is a tough and risky business with roughly only one in five thousand compounds tested by researchers ever reaching clinical application. Pharmaceutical companies and academic researchers are constantly searching for candidate molecules with therapeutic potential. Over the years, various compounds found in botanicals used in traditional medical systems have been turned into drugs or have been the base for synthetic variants. Morphine extracted from the opium poppy, colchicine from the autumn crocus as well as the first semi-synthetic drug, aspirin, made from naturally occurring salicin isolated from the bark of the white willow, are classic examples. Today, scrutinizing traditional herbal remedies for clues that may aid in drug development is a fertile area of research.

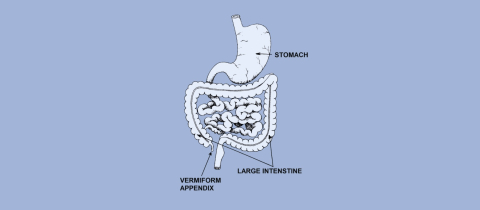

Plants that contain berberine, although usually in combination with other botanicals, have been used in traditional Asian medicine for thousands of years for intestinal problems, diarrhea, parasite infection, lowering of body temperature, toothache and malaria. Researchers fancy is always tickled when some substance has a history of such a long use and for such diverse conditions. Indeed, in the last few decades numerous papers dealing with berberine have been published. Treating cell cultures, animals, and in a few cases, humans, with berberine extracted from plants with alcohol has produced some interesting results that include antioxidant, anti-cancer, cholesterol lowering, antifungal, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and memory enhancing effects. Intriguing, but of course there are numerous compounds that have shown such potential in preliminary studies that have ended up on the large refuse heap of the pharmaceutical industry.

Perhaps the most interesting laboratory finding, given the rising global tide of type 2 diabetes, is the control that berberine may exert over blood sugar. But there is a problem. Berberine is virtually insoluble in water and has low intestinal absorption which means it has poor bioavailability. That is why current research focuses on improved delivery systems. These include nanoparticle formulations that encapsulate berberine to improve bioavailability and synthetic modifications of the molecule to increase solubility. Because of berberine’s poor bioavailability, supplements on the market are likely to be useless. However, some derivative of berberine, may yet make it to the physician’s prescription pad. But it won’t be for weight loss. And don’t hold your breath.